Ever tried to find a "Seminole map in Florida" and ended up staring at a messy patchwork of neon-colored casino markers and historical battlegrounds? It’s frustrating. Honestly, if you just Google the term, you get a weird mix of modern reservation boundaries and 1830s war maps that don’t seem to connect.

Most people think the Seminole story is just about the Everglades. You've probably seen the postcards—airboats, gators, and sawgrass. But if you look at a map from, say, 1823, you’ll see the Seminoles were actually forced into a massive "reservation" in the center of the state, far from the coast. They weren't "Everglades people" by choice; they were survivors who moved south because they had to.

💡 You might also like: How to Cook Stew in a Crock Pot Without Ending Up With Mush

The Map That Changed Everything: The Treaty of Moultrie Creek

In 1823, the U.S. government decided they wanted the best Florida farmland for themselves. They met with Seminole leaders at Moultrie Creek (near St. Augustine) and basically drew a giant box on the map. This box covered about four million acres in the center of the Florida peninsula.

It was a terrible deal.

The boundaries were specifically drawn to keep the Seminoles away from both the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. Why? Because the government didn't want them trading with Cuba or the Bahamas. If you look at an original 1823-1827 map, you can see this "ephemeral" reservation. It stretched from just south of Ocala down toward the northern end of Lake Okeechobee.

But here is the thing: the soil was garbage. It was mostly sand and swamp, making it nearly impossible for the tribe to farm and sustain themselves. This map didn't represent a "home"—it was more like a holding pen.

🔗 Read more: Vanilla Chobani Greek Yogurt: Why It’s Still the One Most People Get Wrong

Where the Seminoles Live Today

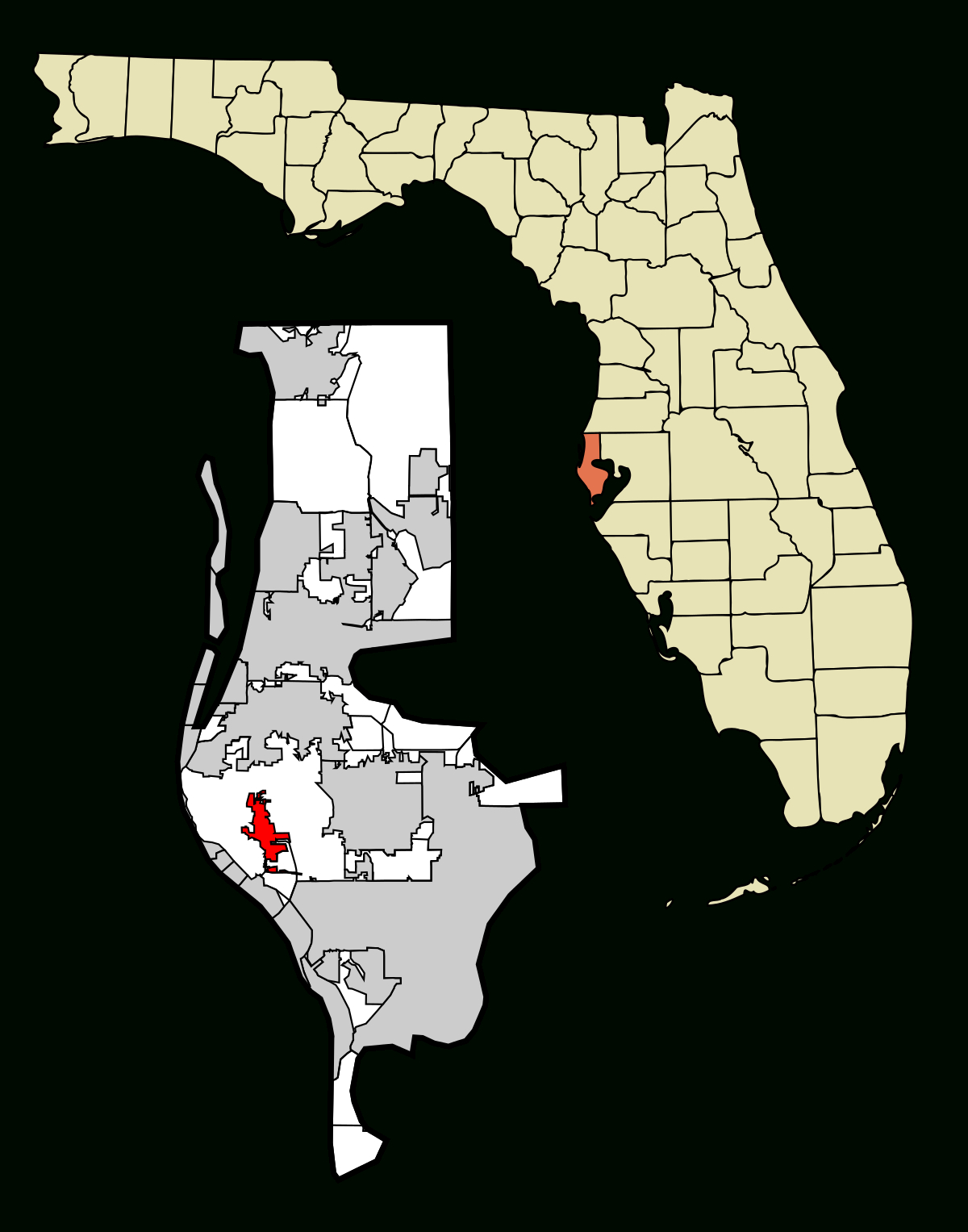

Fast forward to 2026, and the seminole map in florida looks completely different. You won’t find one big block of land. Instead, you’re looking at several distinct sovereign territories scattered across the southern half of the state.

- Big Cypress: This is the largest one. It’s about 52,000 acres in the Florida Everglades, south of Lake Okeechobee. If you want to see the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum, this is where you go.

- Brighton: Located northwest of Lake Okeechobee in Glades County. It’s a huge hub for cattle ranching—which, fun fact, the Seminoles have been doing since the Spanish colonial days.

- Hollywood: This is the headquarters. It’s a smaller urban reservation in Broward County, and honestly, it’s where most of the business happens (including that massive guitar-shaped hotel).

- Immokalee: Situated down in Collier County, this area is deeply tied to the tribe's agricultural roots and modern gaming.

- Tampa: A small but high-traffic reservation in Hillsborough County, mostly known for the Hard Rock Casino.

- Fort Pierce: A newer, much smaller parcel on the east coast.

It’s a sovereign nation within a state. When you cross onto these lands, you’re technically leaving Florida’s jurisdiction in many ways.

The "Ghost Maps" of the Seminole Wars

If you’re a history nerd, the most interesting seminole map in florida isn’t a modern one. It’s the military maps from the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). This was the longest and most expensive Indian War in U.S. history.

Soldiers like Major Francis Dade or General Thomas Jesup were constantly trying to map a landscape that basically wanted them dead. They drew "The Cove of the Withlacoochee"—a massive tangle of islands and swamps in modern-day Citrus and Sumter Counties. On their maps, these areas were often just labeled as "impenetrable."

The Seminoles used this lack of geographic knowledge to their advantage. They didn't have paper maps; they had the land in their heads. While the U.S. Army was getting stuck in the mud trying to find a path for their wagons, the Seminoles were moving through "The Cove" with ease.

Mapping the Escape to the South

By the time the Third Seminole War ended in 1858, most of the tribe had been forcibly moved to Oklahoma. But about 200 to 300 people refused to leave. They retreated so deep into the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades that the government basically gave up on finding them.

The maps from this era show a "retreat" into the southernmost tip of Florida. This is where the modern identity of the Florida Seminole was forged—out of the wet, humid, and wild "River of Grass."

How to Actually Use This Info

If you’re planning a trip or doing research, don't just look for a single pin on a map. You've gotta think in layers.

- For History: Check out the Florida Seminole Wars Heritage Trail. It’s a guide put out by the state that maps out battlefields, forts, and markers from Pensacola all the way down to the Keys.

- For Culture: Head to the Big Cypress Reservation. The Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum has incredible GIS (Geographic Information System) projects where they’ve georeferenced over 400 historical maps to show exactly where old camps and trails were.

- For Nature: Visit the Fakahatchee Strand or the Big Cypress National Preserve. While these aren't "reservation" lands anymore, they are the literal landscape that allowed the Seminoles to remain "Unconquered."

Practical Steps for Your Search

Stop looking for a generic "Seminole map." Instead, try these specific resources for better results:

- The STOF-THPO Portal: The Seminole Tribe’s Historic Preservation Office has a GIS portal. It's mostly for tribal members and researchers, but they often share "story maps" that are public-facing and incredibly detailed.

- Florida Memory: This is the state archive’s website. Search for "Seminole Indian Reserve 1834" to see the hand-colored maps that show the old boundaries before the wars started.

- Native-Land.ca: This is a great interactive tool to see the ancestral territories of the Seminole and Miccosukee people before colonial borders existed.

Maps are never just about lines on paper. They’re about who had the power to draw the lines and who had the courage to cross them. Whether you're standing in the middle of a high-tech casino in Hollywood or trekking through the cypress domes of Big Cypress, you're standing on land that was fought for, lost, and in some cases, reclaimed.