The Siberian tiger is a ghost. It moves through the Russian Far East with a silence that defies its five-hundred-pound frame. If you look at a Siberian tiger range map from a century ago, it looks like a massive, dark ink stain spreading across the face of Asia. It covered Korea, Northeast China, and vast swaths of the Russian interior.

Today? That stain has dried up.

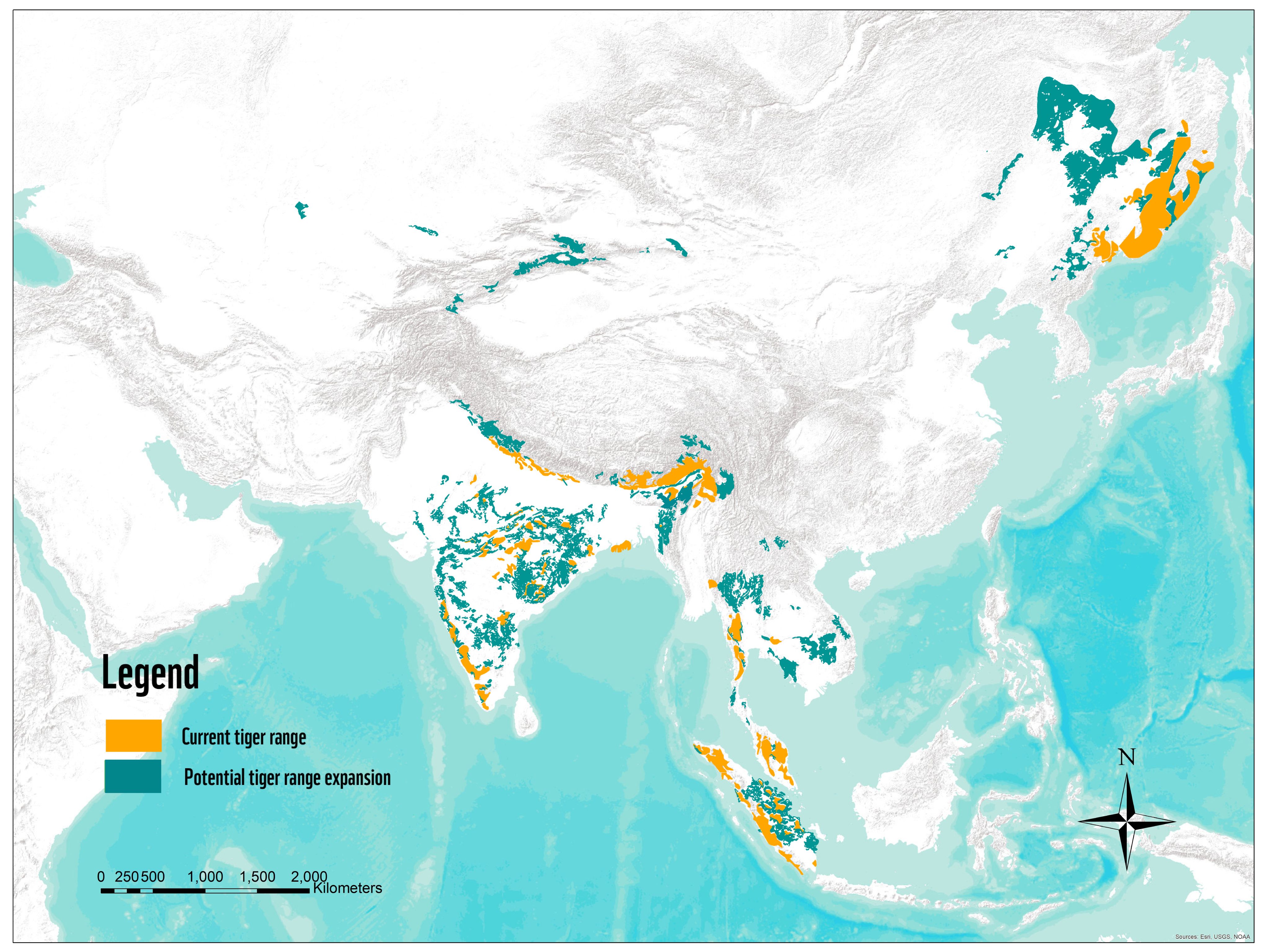

Most people think these tigers—also known as Amur tigers—are scattered across all of Siberia. They aren't. In fact, calling them "Siberian" is a bit of a misnomer that scientists are still trying to correct. They live almost exclusively in a tiny sliver of land along the Sea of Japan. If you want to find them, you have to head to the Primorsky and Khabarovsk Krais in the Russian Far East. That’s the heart of the modern range. It’s a rugged, brutal, and beautiful landscape defined by the Sikhote-Alin mountain range.

Honestly, it's a miracle they’re even there. By the 1940s, there were maybe 40 of these cats left in the wild. Forty. You could fit the entire world population of the planet's largest cat into a single school bus. We almost lost the map entirely.

Mapping the Current Stronghold: The Sikhote-Alin Mountains

If you pull up a modern Siberian tiger range map, you’ll see one big, dominant blob in the Russian Far East. This is the Sikhote-Alin mountain range. It’s the primary fortress for Panthera tigris altaica.

✨ Don't miss: The LA to San Francisco Pacific Coast Highway Trip Most People Do Totally Wrong

Why here?

The mountains offer a mix of Korean pine and Mongolian oak forests. This isn't just about the scenery; it's about the food. Acorns and pine nuts feed the wild boar and red deer. No boars, no tigers. It’s a direct link. The tigers aren't just wandering randomly; they are tethered to the density of their prey. Dale Miquelle, a legendary researcher with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), has spent decades tracking these movements. His work shows that a single male Siberian tiger needs a territory that can reach up to 1,000 square kilometers.

Think about that. One cat needs an area the size of a small city just to find enough snacks to survive the winter.

This massive spatial requirement is why the range looks so fragmented. When you look at the map, you see these "corridors." These are narrow strips of forest that allow tigers to move between larger patches of habitat without being shot or hit by a truck on a logging road. If those corridors get cut off, the population becomes an island. Islands are where species go to die.

The China Connection: A Range Rebounding

For a long time, the Siberian tiger range map stopped dead at the Chinese border. On the Russian side, you had tigers. On the Chinese side, you had empty forests. Decades of heavy logging and poaching in Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces had basically wiped the slate clean.

🔗 Read more: Why the 9 11 Tribute Museum New York NY Had to Close Its Doors

But things are shifting. Sorta.

The Chinese government established the Northeast China Tiger and Leopard National Park in 2017. It’s huge. It covers over 14,000 square kilometers. Because of this, we are seeing the map expand back into China for the first time in generations. It's not just a few strays anymore. We have females with cubs crossing the border. This is a massive deal for genetic diversity.

Why the Border Matters

- Permeability: The border fences between Russia and China were historically a nightmare for wildlife. Now, there are efforts to make them "tiger-friendly."

- Prey Restoration: China is literally trucking in deer to give the tigers something to eat so they don't wander into villages looking for cows.

- Monitoring: We now have camera trap data showing individual tigers moving between the Russian Land of the Leopard National Park and the Chinese side.

The Ghost of Korea and the Southward Reach

Look at an old Siberian tiger range map from the early 1900s. You’ll see the entire Korean Peninsula shaded in. The "Tiger of Joseon" was a cultural icon. Today, the map in South Korea is empty. There hasn't been a confirmed wild tiger in South Korea for over half a century.

While there are occasional rumors of sightings near the DMZ—the heavily fortified strip between North and South Korea—most experts are skeptical. The habitat just isn't there anymore. However, the cultural memory is so strong that there are constant discussions about "rewilding," though the logistics of putting 500-pound apex predators in one of the most densely populated countries on earth are, frankly, terrifying for local politicians.

North Korea is a black box. We know the habitat is there. The Paektu Mountain region should, theoretically, have tigers. But without boots-on-the-ground research or shared data, the North Korean section of the map remains a giant question mark. Most biologists assume there might be a few transients crossing from China, but a stable population? Probably not.

Misconceptions About the "Siberian" Tag

Let’s get real about the name. The term "Siberian" suggests these cats are hanging out in the frozen tundras of northern Russia near the Arctic Circle.

They aren't.

If you put a tiger in the middle of the true Siberian tundra, it would starve. They are temperate forest animals. They need cover. They need the canopy. The Siberian tiger range map is actually much further south than most people realize—roughly the same latitude as Oregon or Northern California.

✨ Don't miss: Why Charleston Hotels Design Local Story Matters More Than You Think

The "Amur" designation is way more accurate because it ties them to the Amur River basin. This river is the lifeblood of the region. It forms the border between Russia and China and dictates where the prey moves. When the river freezes, it becomes a highway for tigers. When it thaws, it's a barrier.

Threats That Shrink the Map

The map isn't static. It breathes. It expands when we protect forests and it shrivels when we get greedy.

Logging is the big one. It's not just about losing trees; it's about the roads. Logging roads bring people. People bring dogs, which carry diseases like Canine Distemper Virus (CDV). In recent years, CDV has become a terrifying new variable on the Siberian tiger range map. A tiger catches it, loses its fear of humans, wanders onto a highway, and that’s the end of that lineage.

Then there's the "human-wildlife conflict." As the range expands back into China, tigers are bumping into people. There was a famous case a few years ago where a tiger named Ustin, who had been released by Vladimir Putin, crossed into China and started raiding goat farms. It made international headlines. It’s funny until it’s your goat, or your kid. Managing the edges of the map is where the real work happens.

The Role of Genetic Bottlenecks

Because the population was once so low (that "busload" of 40 tigers), every tiger alive today is very closely related. This means their "genetic map" is just as fragile as their geographic one. If a specific disease hits, it could theoretically wipe out the entire range because there isn't enough genetic variation to provide resistance.

How to Read a Tiger Map Like a Pro

When you look at a distribution map for any big carnivore, you need to distinguish between three things:

- Resident Range: Where they live, breed, and sleep.

- Transient Range: Where young males wander looking for a girlfriend or a new home.

- Historical Range: Where they used to be before we showed up with rifles and chainsaws.

Most Siberian tiger range maps you find online mix these up. They show a giant shaded area, but in reality, the tigers are only in about 20% of that shaded space. They stick to the valleys. They avoid the high, rocky peaks where there’s no food. They avoid the coastal towns.

What You Can Actually Do

If you’re fascinated by the geography of these cats, don’t just look at a static image. The situation is moving fast.

- Follow the Amur Tiger Center: They are the boots-on-the-ground organization in Russia. Their maps are updated based on annual snow track surveys.

- Check Global Forest Watch: You can overlay tiger range data with real-time deforestation alerts. It’s depressing but necessary.

- Support Corridor Protection: The most important parts of the map aren't the big parks; they are the tiny "threads" of forest connecting them. Organizations like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) focus specifically on these corridors.

The Siberian tiger range map is a living document. It’s a record of a species that refused to go extinct. Right now, the lines are pushing outward. For the first time in a century, the map is growing. That’s a win we don't see often in conservation.

To stay informed, prioritize data from the 2024-2025 census cycles, as these reflect the most recent shifts in Chinese tiger populations. Look for maps that specifically highlight the "Land of the Leopard" National Park and the "Bikin" National Park, as these are currently the most stable anchors for the species. Understanding the map is the first step in ensuring the ink doesn't dry up for good.

Actionable Insights for Following Amur Tiger Conservation

- Verify the Source: Only trust range maps from the IUCN Red List or the WCS. Third-party travel blogs often use maps that are 20 years out of date.

- Monitor the China-Russia Border: Watch news regarding the "Transboundary Preserve." This is the most critical 500 miles of land for the species' future.

- Look for Prey Density Reports: A map showing lots of tigers but low wild boar populations is a map of a population in trouble. Prey stats are the leading indicator of tiger health.

- Use Interactive Satellite Tools: Use Google Earth to look at the Sikhote-Alin mountains. When you see the massive green blocks interrupted by brown grid-like patterns, you're looking at the exact spots where the range is being pressured by the timber industry.