You ever wonder why kids start using slang they’ve never heard at home, or why you suddenly feel the urge to buy a specific brand of sneakers after seeing a stray Instagram post? It isn't just "influence." It’s basically social learning theory, a concept that totally flipped psychology on its head back in the sixties.

Albert Bandura, the guy behind it, realized something pretty simple but massive: we don't just learn by doing things ourselves and getting a "good job" or a "don't do that." We learn by watching. We’re like sponges for behavior.

Before Bandura came along, the big-shot psychologists (think B.F. Skinner) were obsessed with behaviorism. They thought humans were basically just fancy pigeons. You do a thing, you get a treat, you do it again. You do a thing, you get a shock, you stop. Bandura thought that was way too narrow. He argued that if we only learned through trial and error, most of us would probably be dead or seriously injured before we hit puberty.

The Bobo Doll Experiment: More Than Just Kids Hitting Stuff

If you’ve ever taken a Psych 101 class, you’ve seen the grainy footage. A grown-up walks into a room and starts absolutely laying into an inflatable, weighted-bottom clown called a Bobo doll. They punch it. They kick it. They hit it with a mallet. All while shouting things like "Sock him in the nose!"

Then, the researchers let a kid into the room.

The results were wild. The kids didn't just get aggressive; they imitated the exact movements and phrases the adult used. They picked up the mallet. They used the same weird insults. Bandura’s 1961 study proved that social learning theory wasn't just a hunch. It showed that "observational learning" could happen without any rewards or punishments involved. The kid didn't get a cookie for hitting the doll. They just did it because they saw it done.

But here’s the kicker people often miss about the Bobo doll. It wasn't just about violence. It was about the fact that the kids internalised a pattern. This changed how we look at everything from TV parental ratings to how CEOs lead their companies.

How It Actually Works: The Four Steps

It isn't just "see-do." There’s a mental filter involved. Bandura called this "mediational processes." Basically, stuff happens in your head between the time you see a behavior and the time you decide to copy it.

First, you've got to pay Attention. Sounds obvious, right? But if the person you're watching is boring, or you're distracted by your phone, you aren't going to learn a thing. We tend to pay more attention to people we think are high-status, attractive, or similar to us.

Then comes Retention. You have to actually remember what happened. You store the behavior as a mental image or a verbal description. If you forget how the person held the golf club by the time you get to the driving range, the learning chain is broken.

Third is Reproduction. This is the physical (or mental) ability to do the thing. I can watch Steph Curry shoot three-pointers all day. I can pay attention. I can remember his form. But I'm not 6'3" and I don't have his muscle memory. I can't reproduce it perfectly.

Finally, there’s Motivation. This is the "why." Bandura pointed out that we don't just copy everything we see. We weigh the costs and benefits. If we see someone get praised for being "bold" in a meeting, we might try it. If we see them get chewed out for it, we’ll probably stay quiet. He called this vicarious reinforcement. You're learning from their consequences.

Self-Efficacy: The Secret Sauce

Honestly, the most underrated part of social learning theory is a concept Bandura leaned into later: self-efficacy. This is basically your own belief in whether you can actually pull something off.

It’s the difference between saying "I'd like to be a baker" and actually preheating the oven. If you have high self-efficacy, you view difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered. If it’s low, you give up the second the cake collapses. Bandura argued that our environment, our observations, and our internal pep-talks all swirl together to create this sense of "I can do this."

It’s powerful stuff. It explains why some people thrive under pressure while others crumble. It isn't just "talent." It’s the history of what they've observed and the "wins" they’ve logged in their own minds.

Why Social Learning Theory Still Matters in 2026

We live in a world that is basically one giant Bobo doll experiment. Social media is an endless stream of models to imitate. TikTok "challenges," LinkedIn "hustle culture," even the way people talk about mental health—it’s all social learning in real-time.

The Dark Side: Modeling Bad Behavior

We talk a lot about "toxic environments." From a Bandura perspective, a toxic workplace is just a place where bad behavior is consistently modeled and vicariously reinforced. If the person who yells the loudest gets the promotion, guess what? Everyone else starts sharpening their vocal cords.

This applies to the "incivility" we see online, too. When we see public figures get rewarded (with likes, views, or power) for being hostile, it lowers our own inhibitions. It’s not that we "forgot" how to be nice; it’s that the social learning cues are telling us that being mean is the path to success.

The Bright Side: Intentional Role Modeling

On the flip side, we can use this intentionally. Mentorship isn't just a corporate buzzword; it’s a direct application of social learning theory. By placing a junior employee next to a high-performer, you aren't just giving them a teacher. You're giving them a model for "Attention" and "Retention."

In therapy, specifically "modeling therapy," clinicians use this to help people get over phobias. If you're terrified of dogs, watching someone else calmly pet a dog without getting bitten can actually rewire your brain’s fear response. You’re seeing the "vicarious extinction" of the threat.

👉 See also: Positive Mantoux Test Images: What a "Reaction" Actually Looks Like

Common Misconceptions About Bandura’s Work

People often get a few things wrong. They think social learning is just "monkey see, monkey do."

It’s not.

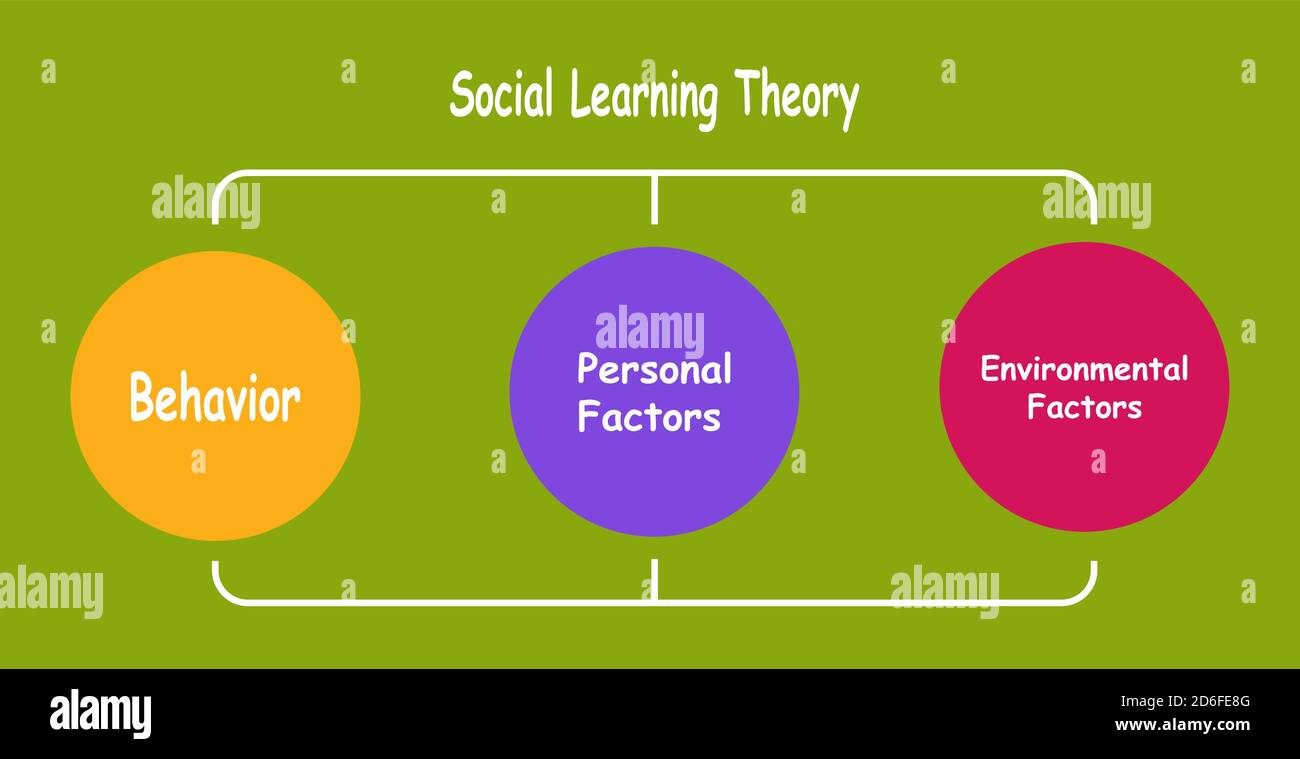

One big nuance is Reciprocal Determinism. This is a fancy way of saying that it’s a three-way street. Your behavior, your personal traits (like your thoughts and feelings), and your environment all influence each other.

- Behavior: You decide to go to a party.

- Environment: The party is loud and overwhelming.

- Personal Factor: You’re an introvert who hates loud noises.

The environment changes your behavior (you leave early), but your behavior also changes the environment (the party is now slightly less crowded). You aren't just a victim of your surroundings. You're an active participant.

Another misconception is that Bandura was saying we have no free will. Far from it. By understanding the "mediational processes," he was actually giving us the tools to break the cycle. Once you realize why you're imitating a certain behavior, you can consciously choose to stop.

Real-World Evidence and Studies

Beyond the dolls, researchers have looked at how this plays out in the long term. A study by Huesmann and Taylor (2006) followed kids for decades and found that those who observed high levels of realistic violence in media were more likely to show aggressive tendencies as adults. It wasn't a 1:1 "see a gun, buy a gun" situation, but it shaped their "normative beliefs"—basically, their sense of what is "normal" behavior in a conflict.

In the business world, a study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology showed that "ethical leadership" trickles down. When employees see supervisors acting with integrity, they don't just follow the rules because of the handbook. They do it because they've internalized the model.

Actionable Insights: Using the Theory to Your Advantage

Knowing this stuff is cool, but using it is better. If you want to change a habit or learn a skill, stop trying to do it in a vacuum.

1. Curate Your Models

You are the average of the people you observe most. If your "Attention" is constantly fixed on people who make you feel inadequate or angry, your brain is recording that as the "default" state of being. Unfollow the models that don't serve your goals. Find "pro-social" models instead.

2. Boost Your Self-Efficacy Through "Micro-Wins"

Bandura found that the best way to build confidence is "mastery experiences." Don't try to run a marathon. Run to the end of the block. That small "win" creates a mental model of success that you can then observe and repeat.

3. Use Verbal Persuasion (Wisely)

The people around you matter. If people you respect tell you that you have the tools to succeed, it actually increases your self-efficacy. Surround yourself with people who don't just flatter you, but who provide constructive, "you-can-do-this" feedback.

4. Watch the Consequences

Pay attention to what happens to others when they act. If you're in a new job, don't just look at what people do—look at what gets rewarded. Is it the person who stays late? Or the person who communicates most clearly? That’s your roadmap for survival.

5. Script Your "Retention"

When you see someone do something you admire—like handling a tough conversation—don't just think "that was cool." Describe it to yourself. "They acknowledged the person's feelings first, then stated their boundary." By putting it into words, you're making it easier for your brain to store and retrieve later.

Social learning theory basically tells us that we are all teachers and we are all students, all the time, whether we like it or not. The "invisible classroom" of our social circle is always in session. Once you realize that, you can start choosing which lessons you actually want to show up for.