Your lawn is dying. Or maybe it’s a swamp. Either way, the culprit is usually that buried plastic box you haven't opened in three years. Inside sits the sprinkler system water valve, the gatekeeper of your entire landscape. Most homeowners treat these things like "set it and forget it" technology, but irrigation valves are mechanical heart valves. They fail. They leak. They get stuck. Honestly, most people don't realize their valve is broken until the water bill hits $400 or the neighbor mentions a river running down the driveway.

Irrigation valves are surprisingly simple yet incredibly finicky. They use a rubber diaphragm and an electromagnetic solenoid to control high-pressure water. Think of it like a dam. When the controller sends 24 volts of electricity to the solenoid, it lifts a tiny plunger. This changes the pressure balance inside the valve, allowing the diaphragm to lift and water to rush through. It’s a delicate dance of physics. If a single grain of sand gets stuck in the bleed screw or the diaphragm tears just a millimeter, the whole system collapses.

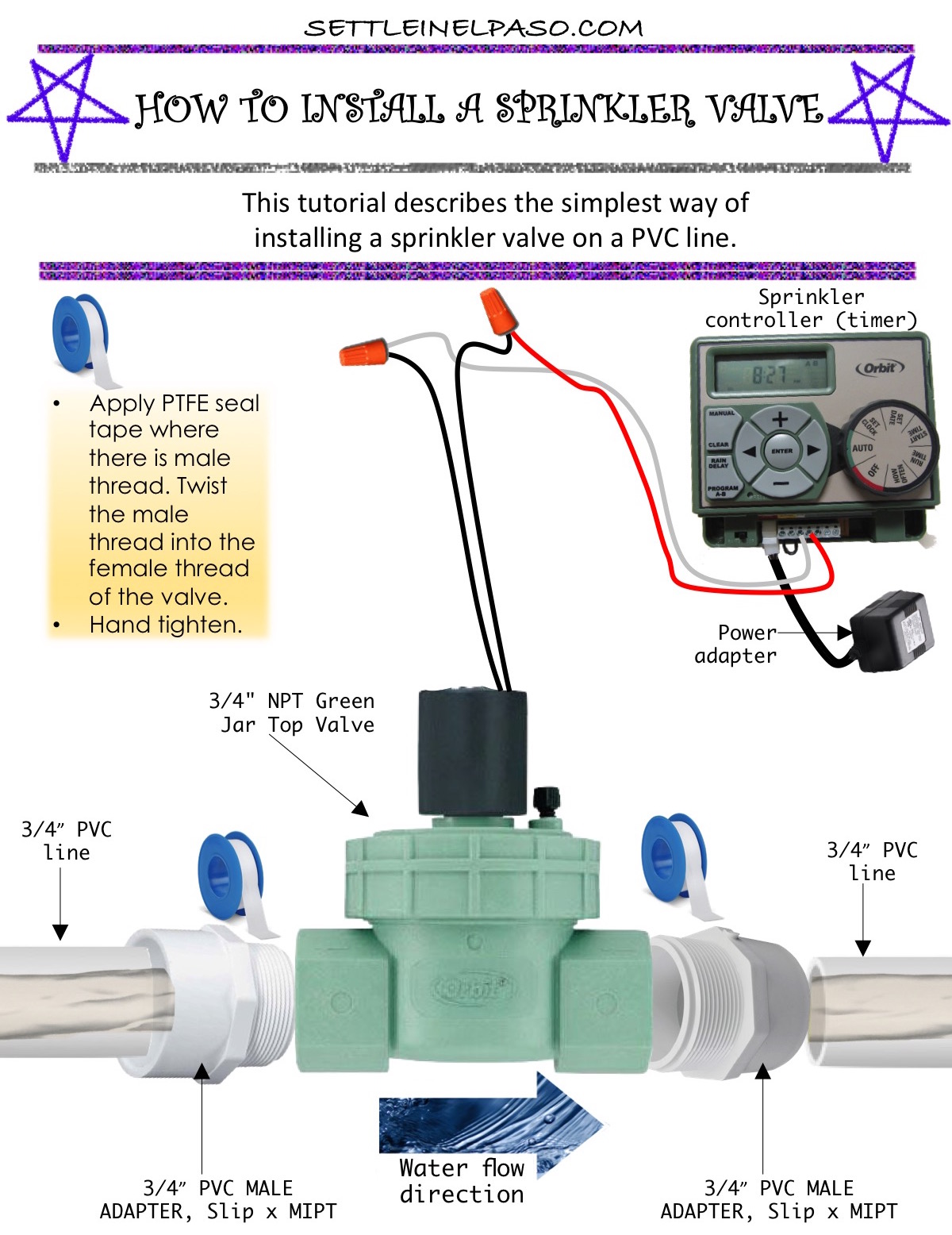

The Anatomy of a Sprinkler System Water Valve

You’ve got a few different types of valves, and knowing which one you’re staring at matters. Most residential setups use inline valves, which sit underground in a plastic box. Then you have anti-siphon valves, which are usually above ground and include a backflow preventer. These are legally required in many regions to stop dirty lawn water from sucking back into your drinking water. If you see a valve with a "hat" or a bell-shaped top, that’s your backflow protection.

The solenoid is that cylinder with two wires coming out of it. It’s the most common point of failure. You can actually turn the water on manually by twisting the solenoid about a quarter turn counter-clockwise. It’s a great trick for testing zones without running back to the garage controller. Just don't over-tighten it when you're done, or you'll snap the O-ring.

Beneath the solenoid is the diaphragm. This is a reinforced rubber disc. Over time, the chlorine in city water or the minerals in well water make the rubber brittle. It cracks. When it cracks, the valve can't close all the way. This is why you see "weeping" heads—sprinklers that constantly trickle water even when the system is off. It’s annoying. It’s wasteful. It’s also a cheap $5 fix if you just replace the rubber instead of the whole valve.

Why Your Valves Keep Failing

Heat and grit. That's the short version. In places like Arizona or Texas, the ground gets hot enough to bake the plastic. In colder climates, if you don't blow out the lines, the water inside the sprinkler system water valve freezes, expands, and cracks the housing. Then there's the debris. If a pipe breaks upstream, dirt enters the line and settles right in the valve seat. It’s like getting a pebble in your shoe; the valve just can’t "step down" and seal shut.

- The "Humming" Solenoid: If you hear a buzz but no water, the plunger is stuck or the coil is fried.

- The Mystery Leak: If there's a permanent puddle around your valve box, the body of the valve might have a hairline fracture.

- Zone Won't Turn Off: Usually a torn diaphragm or a blocked port.

I've seen people replace their entire $500 controller because a zone wouldn't fire, only to realize the $15 solenoid had a loose wire. Always check the valve first. It’s the "boots on the ground" part of your irrigation system. You can use a multimeter to check for 24-28 VAC at the valve. No juice? It’s the wiring or the clock. Got juice but no water? It’s the valve.

Repairing vs. Replacing: The Honest Truth

Most pros will tell you to just "cut it out and start over." That’s because labor is expensive and parts are cheap. But if you’re a DIYer, you can usually perform "valve surgery." You buy the exact same model of valve from the store, unscrew the top (the bonnet), and swap the internals into the old body. This saves you from digging a massive hole and cutting PVC pipes. It’s a 10-minute job versus a two-hour headache.

Be careful with the brands. Rain Bird, Hunter, and Irritrol are the big players. They aren't interchangeable. A Rain Bird diaphragm won't fit a Hunter Jar-Top valve. If you aren't sure what you have, take a photo of the top of the valve or bring the old solenoid to the hardware store.

Dealing with the Master Valve

Some systems have a "Master Valve." This is a single sprinkler system water valve located right at the main water source. It opens every time any zone is running. It’s a fail-safe. If a regular zone valve gets stuck open, the Master Valve shuts off and stops the flood. If your entire system isn't working—no matter what zone you click—check the Master Valve. It’s the literal gatekeeper.

💡 You might also like: The Only Fourth Of July Trifle Recipe You Actually Need This Year

Real-World Troubleshooting Steps

If you’re standing over a muddy hole wondering why your life is like this, try this sequence. First, try the manual bleed screw. It’s a little plastic thumb-screw on top of the valve. Open it. If water sprays out and the sprinklers pop up, your plumbing is fine, but your electronics are likely dead.

Next, check the wiring. Those grease-filled wire nuts are there for a reason. Copper corrodes instantly in wet soil. If the connection looks crusty, snip it, strip it, and use a fresh waterproof connector. Honestly, about 40% of "broken" valves are just bad wire splices.

If the electronics are good but the valve won't shut off, you have to open it up. Shut off the main water supply first! Seriously. If you unscrew a valve bonnet while the water is pressurized, you’re going to get a 60-PSI geyser to the face. Once the water is off, remove the screws (usually four to six) or unscrew the jar-top ring. Look for a tiny piece of rock or a tear in the rubber. Clean it out, put it back together, and cross your fingers.

Better Maintenance for Longevity

You really should be cleaning out your valve boxes once a year. Spiders, toads, and silt love those boxes. If the box fills with dirt, the wires rot faster and the solenoids overheat. Also, make sure your valve box has a layer of gravel at the bottom. This allows for drainage so the valves aren't literally sitting in a bath of mud.

It’s also worth mentioning pressure regulation. If your house has high water pressure (over 80 PSI), your valves will "hammer." That’s that loud thumping sound you hear in the walls when the sprinklers turn off. It shreds diaphragms. Installing a pressure regulator or using valves with built-in regulation (like the Rain Bird PRS-D) can double the lifespan of your system.

Actionable Steps for a Healthy System

Don't wait for a brown lawn to take action. Start with these three specific moves:

- Locate and Map: Open every valve box on your property. Label the valves with a permanent marker on the inside of the lid (e.g., "Front Grass," "Flower Bed"). You’ll thank yourself when there’s a midnight leak.

- Test the Manual Bleed: Once a season, turn each valve on using the manual screw or solenoid twist. This ensures the mechanical parts aren't seized up and allows you to check for leaks under pressure.

- Inspect the Solenoids: Look for frayed wires or melted plastic. If a solenoid feels hot to the touch while running, it’s drawing too much current and is about to fail. Replace it now for $20 before it fries your expensive controller.

If a valve is older than 10 or 15 years, the plastic can become brittle. At that point, stop patching it. Cut it out, use "slip fixes" (telescoping PVC fittings) to make the repair easy, and install a modern, high-quality valve. It's a weekend project that prevents a month-long headache.