You’ve seen it a thousand times. Someone at the gym is flailing around on a giant plastic orb, neck straining, back arching, looking more like a fish out of water than an athlete. It’s the stability ball crunch. Most people do it because they want a six-pack, but honestly, most people are just wasting their time. They’re using momentum instead of muscle. They’re treating the ball like a recliner.

The reality is that the stability ball is one of the most misunderstood pieces of equipment in the functional fitness world. Developed in the 1960s by Aquilino Cosani and originally known as the "Swiss Ball" in physical therapy circles, it wasn't meant for mindless crunches. It was designed for neuro-rehabilitation. When you bring it into the weight room, you’re dealing with a tool that forces your body to manage instability. That’s the "secret sauce" that makes it better than a floor crunch—if you actually know how to use it.

The Science of Why Stability Ball Crunches Beat Floor Crunches

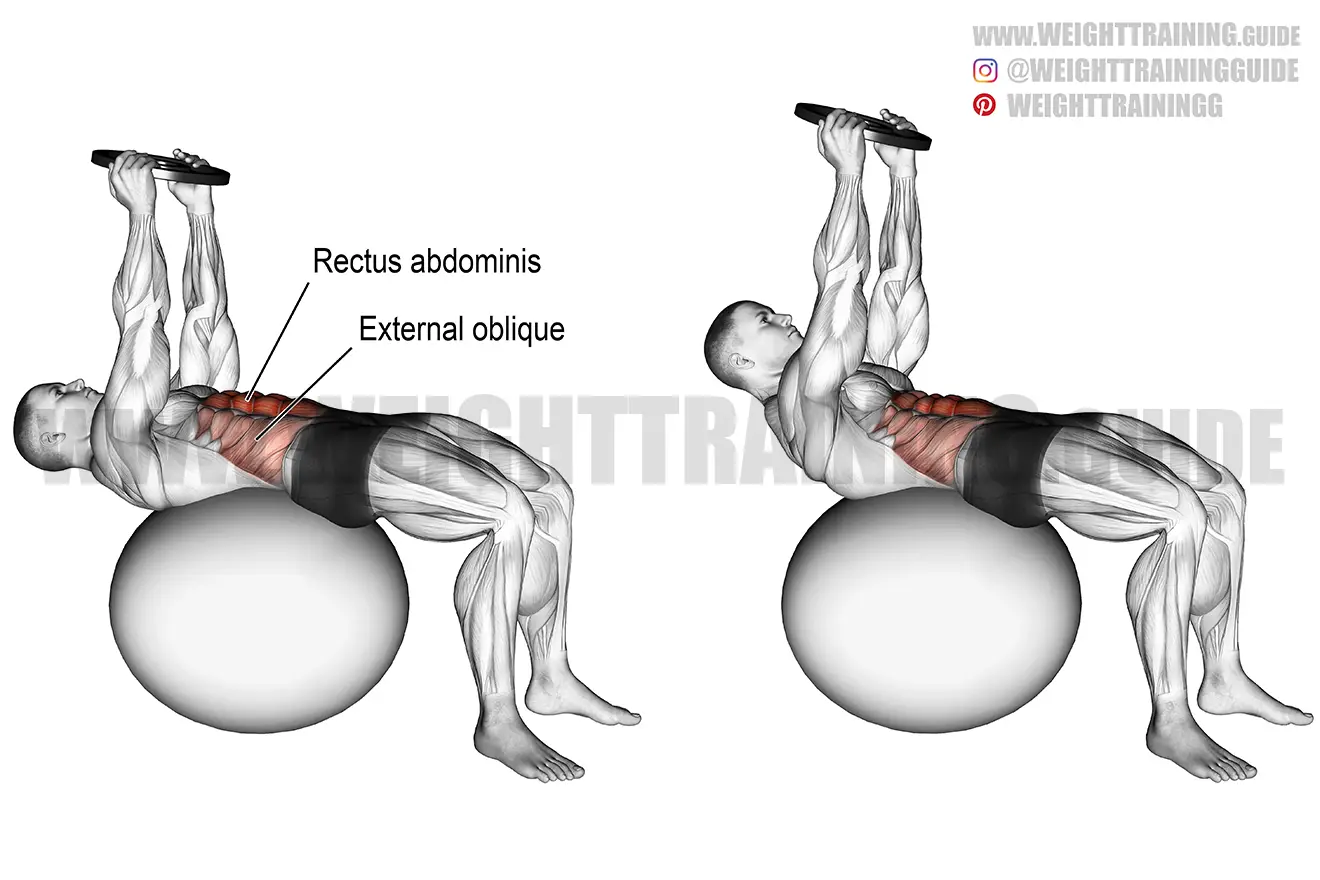

Let’s get nerdy for a second. Why bother with the ball at all? Research published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research has shown that performing abdominal exercises on an unstable surface increases electromyographic (EMG) activity in the rectus abdominis and the obliques compared to stable surfaces. Basically, your muscles fire harder because they’re terrified you’re going to fall off.

But there’s a bigger reason: Range of Motion.

When you lie on the floor, your spine is flat. You can only crunch "up." You’re limited to about 30 degrees of spinal flexion. On a ball, your spine can actually extend backward over the curve. This puts the rectus abdominis under a pre-stretch. In exercise science, we call this the stretch-shortening cycle. By starting the movement from a position of extension (arched back slightly over the ball), you recruit more muscle fibers through a greater range of motion. It’s the difference between doing a partial squat and going all the way down.

Stop Hurting Your Neck and Start Engaging Your Core

Most people complain of neck pain during a stability ball crunch. That’s a huge red flag. If your neck hurts, your abs aren't working; your sternocleidomastoid is doing the heavy lifting. You've got to tuck your chin—sorta like you're holding a tennis ball between your chin and your chest—and keep it there.

Don't pull on your head. Seriously. Stop it.

Instead, try touching your temples or crossing your arms over your chest. If you're a beginner, reach your hands toward your knees. The goal is to move your ribcage toward your pelvis. That’s it. That’s the whole "crunch." It’s a small, controlled contraction. You aren't trying to sit all the way up. If your lower back loses contact with the ball or you start sliding forward, you’ve gone too far.

Setting Up the Perfect Rep

- Sit on the ball and walk your feet forward until your lower and middle back are supported.

- Your feet should be shoulder-width apart. Wider for more stability, narrower if you want to challenge your balance.

- Lean back so your spine follows the contour of the ball. You should feel a slight stretch in your abs.

- Exhale hard as you lift your shoulder blades off the ball.

- Hold for a split second at the top. Squeeze like someone is about to poke you in the stomach.

- Slowly—and I mean slowly—lower back down.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Progress

I see it every day. People bounce. They use the elasticity of the ball to catapult themselves upward. That’s great for physics, but it’s terrible for muscle growth. If you’re bouncing, you’re letting the air inside the ball do the work your muscle should be doing.

Another big one? Hip flexor dominance.

If you feel a "tugging" in the front of your thighs near your groin, you’re using your hip flexors to pull your torso up. To fix this, press your heels into the floor. Imagine you’re trying to push the floor away from you. This creates reciprocal inhibition, which basically tells your hip flexors to relax so your abs can take over.

Then there’s the ball size. If you’re 5'4" trying to use a 75cm ball, you’re going to have a bad time. You won't be able to get the right leverage. Conversely, a tall person on a tiny ball will feel like they’re doing crunches on a grape. Generally, if you sit on the ball and your knees are at a 90-degree angle, you’ve found the right fit.

Variations for When You Get Bored

Once you’ve mastered the basic stability ball crunch, you can’t just keep doing three sets of fifteen forever. Your body adapts. It gets efficient. Efficiency is the enemy of fat loss and muscle hypertrophy.

- Weighted Crunches: Hold a dumbbell or a weight plate against your chest. Do not hold it behind your head unless you have incredibly mobile shoulders and a very strong core, as this increases the lever arm and can strain the lower back.

- The Oblique Twist: As you crunch up, rotate one shoulder toward the opposite hip. Focus on the rotation coming from your torso, not just swinging your elbows.

- Medicine Ball Reach: Hold a light medicine ball and reach it toward the ceiling as you crunch. This shifts the center of gravity and forces your deep stabilizers to kick in.

Is It Safe for Everyone?

Not necessarily. If you have a herniated disc or acute lower back pain, the stability ball crunch might be too much extension for you right now. Dr. Stuart McGill, a leading expert in spine biomechanics, often suggests that repeated spinal flexion (the crunching motion) can put undue stress on the intervertebral discs if done excessively or with poor form.

For people with back issues, "dead bugs" or "bird-dogs" on the floor might be a better starting point. But for a healthy trainee, the ball offers a level of protection that the floor doesn't—it supports the natural curve of the lumbar spine while allowing the muscles to work.

The Myth of Spot Reduction

We have to address the elephant in the room: you cannot crunch away belly fat. Doing 500 stability ball crunches a day will give you incredibly strong abdominal muscles, but they will remain hidden under a layer of adipose tissue if your nutrition isn't on point.

Think of crunches as building the "bricks" of your six-pack. Your diet is what removes the "tarp" covering them. You need both. But the benefit of using the ball goes beyond aesthetics. A strong core—meaning the rectus abdominis, the transversus abdominis, the multifidus, and the obliques—acts as a natural weight belt. It protects your spine during heavy lifts like squats and deadlifts. It improves your posture. It even helps with balance as you age.

How to Program This Into Your Workout

Don't do your ab work at the very beginning of a heavy lifting session. You need those core muscles fresh to stabilize your spine during your big movements. Save the stability ball crunch for the end of your workout or pair it in a superset with a non-competing movement like push-ups or lat pulldowns.

Start with 2 sets of 10 to 12 reps. Focus entirely on the tempo. Try a "2-1-2" tempo: two seconds on the way up, a one-second pause at the top, and two seconds on the way down. If you do this correctly, twelve reps will feel harder than fifty "fast" reps.

Real-World Implementation Steps

If you’re ready to actually see results from this movement, stop treating it as an afterthought. Most people toss in a few sets at the end of their workout when they're already exhausted and just want to go home. That leads to sloppy form.

Your Action Plan:

✨ Don't miss: Low Calorie Dinner Recipes: Why Most People Are Doing Weight Loss Meals All Wrong

- Check your equipment: Ensure the ball is firm. A soft, under-inflated ball provides too much stability (ironically) and reduces the effectiveness of the exercise.

- Master the "Hollow Body" feeling: Before you even move, pull your belly button toward your spine. This engages the transversus abdominis, the deep "corset" muscle of your core.

- Focus on the Rib-to-Pelvis connection: Imagine a string connecting your bottom rib to your hip bone. Your only goal is to make that string shorter.

- Progress slowly: Don't add weight until you can perform 15 reps with perfect control and zero neck pain.

- Frequency matters: The core recovers quickly. You can train crunches 2-3 times a week, but give yourself at least 48 hours between sessions if you're using added resistance.

The stability ball crunch is a phenomenal tool for core development, but only if you respect the mechanics of the movement. Stop rushing. Stop bouncing. Focus on the squeeze, embrace the wobble, and you’ll actually start to feel the muscles you’ve been trying to find for years.

Next Steps for Your Core Routine

To maximize your results, combine the stability ball crunch with "anti-extension" exercises like planks or stir-the-pot (also done on the ball). While the crunch works on flexion, anti-extension movements teach your core to resist movement, which is the primary job of your midsection during daily life. Check your ball's air pressure before your next session—if you can sink more than two inches into it when sitting, grab the pump and firm it up. This small change alone will significantly increase the muscle recruitment during your next set.