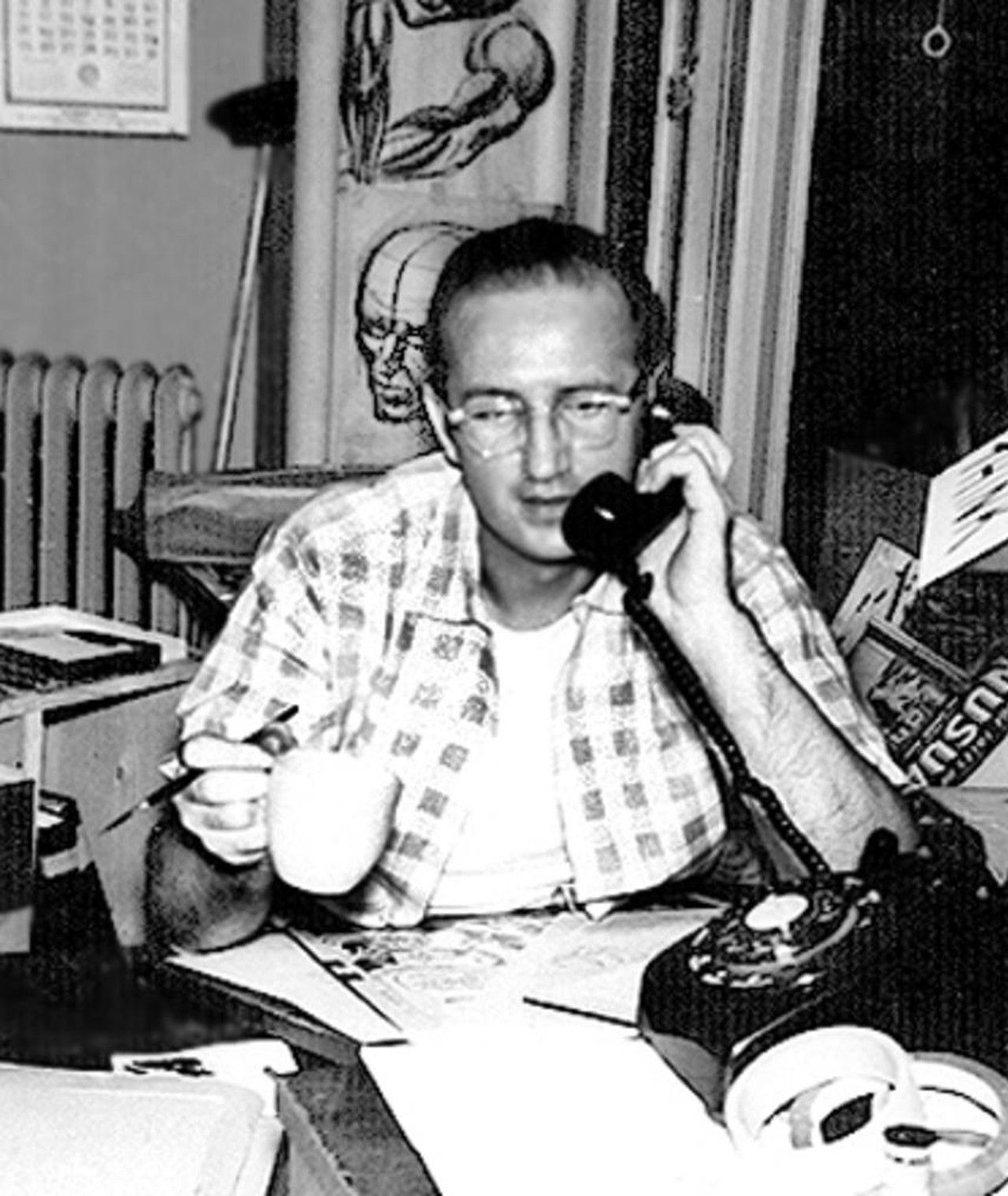

You know Steve Ditko. Or at least, you think you do. He’s the guy who gave Spider-Man his webs and Doctor Strange his psychedelic dimensions. But if you really want to understand the man who walked away from Marvel at the height of its silver age glory, you have to look at a character most people have never heard of.

Mr. A.

💡 You might also like: Slow Dancing in a Burning Room Guitar: Why It Is Still the Hardest Riff to Master

He wears a metal mask. A white suit. A matching fedora. He doesn’t have spider-powers or mystical capes. He has a philosophy. And a calling card that is half-white and half-black. No gray.

Honestly, Mr. A is the most "Ditko" thing Ditko ever did. It’s where the subtext of his Marvel work became the absolute, shouting text of his independent work. If you’ve ever wondered why Rorschach in Watchmen is so obsessed with "never compromising," you’re looking at the direct DNA of Mr. A.

The Birth of an Uncompromising Vigilante

In 1967, Ditko was done with the mainstream. He’d left Stan Lee and the "Marvel Method" behind. He wanted to say things that the Comics Code Authority—the censors of the time—would never allow.

He found his outlet in Witzend, an independent magazine started by his friend and fellow legend Wally Wood. This wasn't for kids. It was for people who wanted to see what happened when an artist was truly unleashed.

Enter Rex Graine. By day, he’s a hard-nosed newspaper reporter. By night (or whenever the moral code demands it), he is Mr. A.

The name is a direct reference to the Aristotelian law of identity: A is A. Basically, it means a thing is what it is. A fact is a fact. Good is good, and evil is evil. In Ditko’s world—and the world of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, which Ditko followed religiously—there is no middle ground. There is no "he’s a good guy who made a mistake." There is only the choice.

Why the White Suit and the Black-and-White Card?

Most superheroes are defined by their powers. Mr. A is defined by his refusal to tolerate moral "grayness."

You see it in the art. Ditko’s work on Mr. A is stark. It’s harsh. The shadows are pitch black, and the highlights are blindingly white. It’s visual storytelling as a polemic.

When Mr. A confronts a criminal, he doesn't offer a hand up. He doesn't wonder about the perpetrator's "difficult childhood." He sees a person who has chosen to violate the rights of others.

There’s a famous, or perhaps infamous, scene in an early story. A criminal is hanging off a ledge. He’s pleading for his life. A typical hero—Peter Parker, for instance—would strain every muscle to save him.

Mr. A? He just watches.

He explains, quite calmly, that the criminal has forfeited his right to life by his own actions. If the man falls, it’s not because Mr. A killed him; it’s because gravity and the man’s own choices did. It’s cold. It’s brutal. And for Ditko, it was the only logical outcome of a moral universe.

The Question vs. Mr. A: What’s the Difference?

A lot of fans get these two mixed up. It makes sense. They both wear the suit and the hat. They both have the "no face" look.

But there’s a key distinction:

- The Question (Vic Sage): Created for Charlton Comics. He had to pass the censors. He was tough, but he still operated within the general "hero" framework of the 1960s.

- Mr. A: The "pure" version. No filters. No editors telling Ditko to tone it down.

While DC Comics eventually bought the Question and turned him into a conspiracy theorist or a Zen seeker, Mr. A remained Ditko’s personal property until the day he died in 2018. He kept drawing Mr. A stories for decades, publishing them in small-press "fanzines" and independent collections like The Avenging World.

The Alan Moore Connection: How Mr. A Created Rorschach

If you've read Watchmen, you know Rorschach. He’s the fan favorite. The guy who says, "Not even in the face of Armageddon."

Alan Moore actually wanted to use the Charlton characters like The Question. DC said no because they had big plans for them. So, Moore created analogues.

Rorschach is Moore’s take on Mr. A. But here’s the kicker: Moore intended Rorschach to be a critique. He thought the "no compromise" philosophy was, well, kind of insane in a real-world context.

Ditko, ever the straight shooter, didn't much care for the parody. When asked about Rorschach, he reportedly said, "He’s like Mr. A, except Rorschach is insane."

It’s a fascinating loop. The "real" version is a man of perfect, rational logic (in Ditko’s view). The "homage" is a broken, smelly loner living in a dumpster.

The Philosophy of "A is A" in Action

To understand the stories, you have to understand Objectivism. It’s not just a political stance; for Ditko, it was a way of seeing reality.

He believed that:

- Reality is objective. It doesn't matter what you "feel." What is, is.

- Reason is man’s only tool. Emotions are not a guide to action.

- Justice is absolute. If you reward the "bad" even a little, you are punishing the "good."

This is why Mr. A is so polarizing. In one story, he might pursue a murderer. In another, he’s lecturing a "neutral" person who refuses to take a side. To Mr. A, being neutral is just as bad as being evil. By not opposing the wrong, you're helping it happen.

It makes for dense reading. Sometimes the characters stop fighting and just give five-page speeches about the nature of truth. It’s not "fun" in the way a movie like The Avengers is fun. It’s meant to be a challenge.

Why Does Mr. A Still Matter Today?

We live in an era of "anti-heroes" and "shades of gray." Every villain has an origin story that makes us feel sorry for them. Every hero is "flawed" and "relatable."

Mr. A is the exact opposite of that trend.

He is a reminder of a time when a creator was so dedicated to his personal truth that he was willing to walk away from fame and fortune to draw what he believed in. Ditko didn't want your approval. He didn't want to be "relatable." He wanted to be right.

Whether you agree with the philosophy or not, there is something undeniably powerful about the purity of the work. You don't see this kind of conviction in corporate comics anymore. You see committees. You see brand management.

💡 You might also like: Top Joe Rogan Episodes: The Ones That Actually Change How You Think

With Mr. A, you just see Steve Ditko.

How to Explore the World of Mr. A

If you want to actually read this stuff, it’s a bit of a treasure hunt. Because Ditko kept his work independent, it’s not always sitting on the shelf at your local bookstore.

What to look for:

- Witzend #3 and #4: These contain the earliest, most iconic stories.

- The Avenging World: A collection of Ditko’s philosophical comics that hits like a sledgehammer.

- Mr. A. #1 (1973): Published by Comic Art Publishers, this is a great entry point if you can find a copy.

- Robin Snyder’s Publications: Ditko spent his later years working with editor Robin Snyder to put out small books like The Ditko Public Service Package.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Look for the "Law of Identity" in visual form. Go back and look at Ditko’s final issues of The Amazing Spider-Man (around issue #38). You can see the seeds of Mr. A in how Peter Parker starts treating student protesters and "moochers."

- Compare and Contrast. Read a 1980s Question comic by Denny O'Neil and then read a Mr. A story. Notice how the DC version introduces doubt and "gray" areas, while Ditko’s version remains a solid, unmoving rock.

- Support Independent Collections. Many of Ditko's independent works have been collected in recent years by publishers like IDW or through Snyder's direct efforts. These are the best ways to see the art as it was intended—without the muddying effects of 1960s newsprint.

Mr. A isn't for everyone. He wasn't meant to be. But if you want to see the "hidden" heart of comic book history, he is the place to start. He is the man who never compromised, even when the rest of the world moved on.

End of Article.

Actionable Insight: To truly appreciate the history of the medium, track down a reprint of The Avenging World. It provides the necessary context to understand why Steve Ditko’s departure from Marvel was a philosophical necessity rather than just a business dispute.