You just spent twenty minutes sweating over a sharpening stone. The edge looks shiny, and it cuts paper—kinda. But it still feels "toothy." It catches. That’s because you haven't finished the job. Most people think sharpening ends with the stones, but honestly, learning how to strop a blade is the difference between a tool that just cuts and one that glides through wood or hair like it’s not even there.

Stropping is the "lost art" of the modern kitchen and workshop. It’s the final stage of alignment. When you sharpen a knife on a whetstone, you’re removing metal to create a new edge. This process inevitably leaves behind a "burr"—a microscopic, ragged wire of metal hanging off the apex. If you don't remove that, your knife will feel sharp for exactly three cuts before that wire edge rolls over and makes the blade feel dull again. Stropping fixes this.

The Science of the Micro-Edge

Think of your blade edge under a microscope. It’s not a smooth V. After stones, it looks like a serrated saw blade with tiny metal shards clinging to life. If you’ve ever used a straight razor, you know the leather strap is non-negotiable. For a pocket knife or a chef’s knife, it’s just as vital.

Leather is the traditional choice because it has a natural "give." When you push a blade across a hard stone, you’re grinding. When you pull it across leather, the surface deforms slightly, wrapping around the very tip of the edge to polish away those microscopic imperfections. You aren't really removing "bulk" metal here. You’re burnishing. It’s the difference between sanding a piece of wood and buffing it with wax.

A common misconception is that stropping is just for show. It’s not. In fact, a study by Larrin Thomas at Knife Steel Nerds has shown that stropping with fine diamond compounds can significantly reduce the edge radius, making the blade objectively sharper than what is possible with stones alone. However, there’s a catch. If you over-strop or use too much pressure, you actually round the edge, making it duller. It’s a delicate balance.

What You Actually Need to Get Started

You don't need a $200 bespoke leather setup from a boutique shop in Japan. You can literally use a piece of cardboard or an old leather belt. But if you want real results, you need a flat surface.

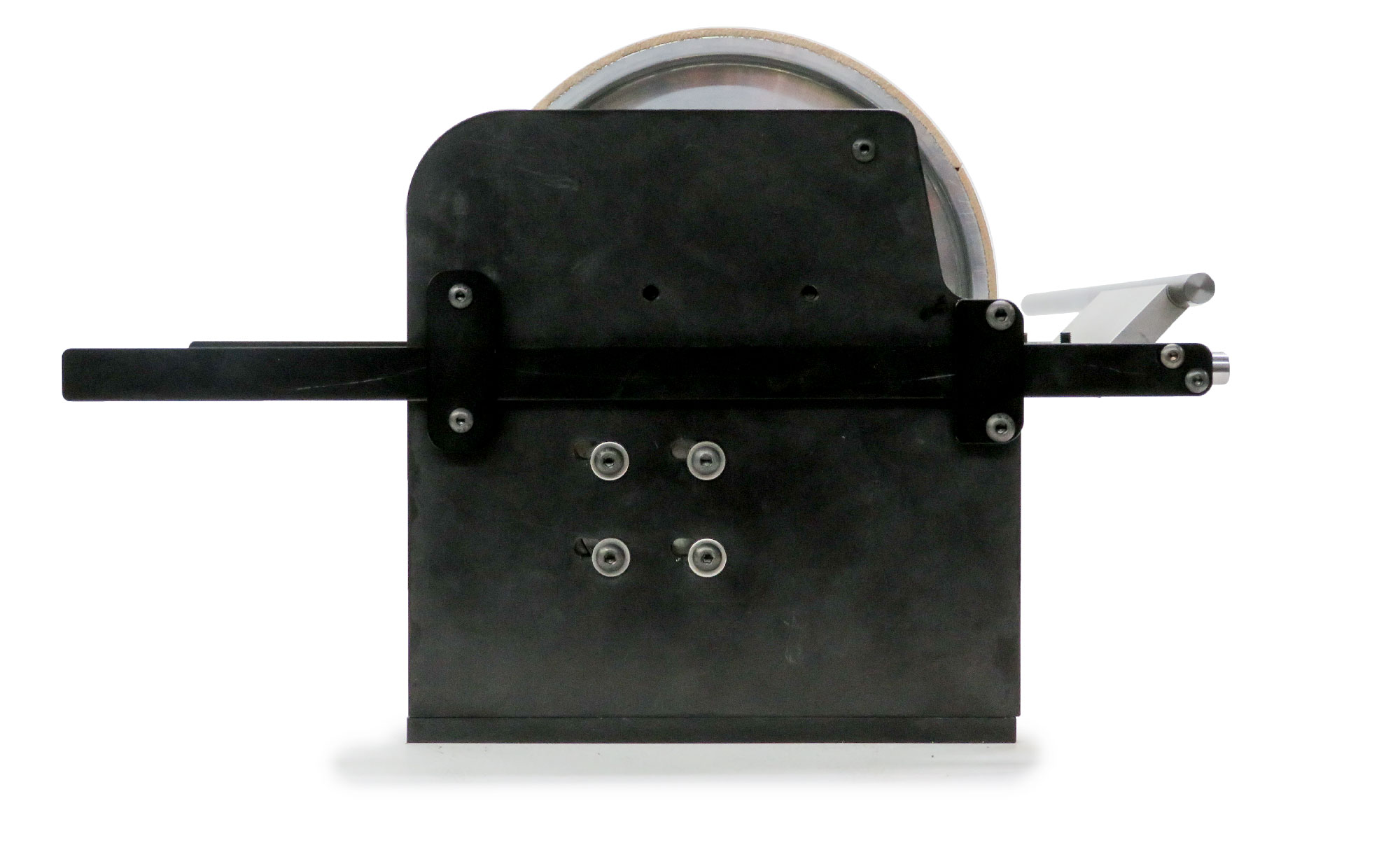

Most pros use a paddle strop. It’s basically a piece of wood with leather glued to it. Why wood? Because if the leather is just hanging in the air (like a barber's strop), it’s too easy for a beginner to "dish" the edge. The wood provides a hard backing that keeps your angles consistent.

👉 See also: Why the Bride of Frankenstein Wig is Harder to Get Right Than You Think

The Abrasives

Raw leather is okay, but "loaded" leather is better. You load a strop by rubbing a polishing compound onto it.

- Green Compound: Usually chromium oxide. This is the gold standard. It’s roughly 0.5 microns. Cheap, effective, and turns your strop a weird Hulk-green color.

- Diamond Paste: The modern choice. It stays sharp longer and cuts through high-carbide "super steels" that chromium oxide struggles with.

- Plain Leather: Good for a final, final touch. It just cleans off any leftover compound or dust.

How to Strop a Blade Without Ruining the Edge

The technique is simple, but your muscle memory will try to sabotage you. In sharpening, you usually push the edge forward (edge-leading). In stropping, you always pull the edge away (edge-trailing). If you push the edge into the leather, you’ll cut the strop. You’ll also feel like an idiot. Don't do it.

First, lay the blade flat on the strop. Slowly raise the spine until the cutting bevel is touching the leather. You want to match the angle you used on your sharpening stones. If you sharpened at 15 degrees, strop at 15 degrees.

Apply very light pressure. I’m talking about the weight of the knife plus maybe a feather's touch. Pull the knife toward you, spine-first. Sweep the entire edge from heel to tip. When you reach the end of the stroke, lift the knife, flip it over, and push it away from you on the other side.

Repeat this maybe 10 to 15 times per side. You don't need a hundred passes. If it’s not sharp after 20 passes, your problem isn't the strop—it’s that you didn't spend enough time on the stones. The strop isn't a miracle worker; it’s a finisher.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Sharpness

The biggest mistake? Pressure.

People think pushing harder makes it sharper. It does the opposite. Because leather is soft, pushing hard causes the leather to compress and then "roll up" over the tiny apex of your knife. This rounds the edge. You’ll end up with a blade that looks like a mirror but won't even cut a tomato.

Another big one is "flipping" the knife on the edge. When you finish a stroke, some people have a habit of rolling the knife over the spine while it's still in contact with the leather. This can also round the edge. Lift the knife completely off the surface before you flip it. It feels slower, but it’s how you get that "scary sharp" result.

Is Cardboard Actually Good?

Yes. Honestly, if you're in a pinch, the back of a legal pad or a clean piece of corrugated cardboard works surprisingly well. The silicates in the paper act as a very mild abrasive. It won't give you a mirror polish, but it’ll definitely rip a burr off a kitchen knife in a few seconds.

Advanced Stropping: The Compound Debate

Some guys get really intense about micron sizes. They'll start with a 4-micron diamond spray, move to a 2-micron, then a 1-micron, and finish with a 0.25-micron emulsion. Unless you are a competitive woodcarver or a straight-razor enthusiast, this is overkill.

For the average person, a single strop with green compound is all you need. If you’re working with modern powdered steels like S30V, M390, or MagnaCut, you might find that chromium oxide (green) feels a bit slow. Those steels have carbides that are literally harder than the abrasive in the green wax. In that case, grab a small bottle of 1-micron diamond spray. It’ll bite into those tough steels much faster.

Real-World Evidence: Does It Really Matter?

I remember talking to a veteran woodworker who swore he hadn't touched a whetstone in six months. He just stropped his chisels every 30 minutes of work. That’s the secret. Stropping isn’t just for after-sharpening; it’s for maintenance.

When you use a knife, the edge doesn't always "dull" by losing metal. Often, the very tip just gets slightly bent to one side (micro-rolling). A few passes on a strop realigns that tip. If you strop your kitchen knife once a week, you might only need to go to the stones once a year. It saves your steel and it saves your time.

Your Actionable Maintenance Plan

Stop overthinking the grit and the leather quality. If you want a sharp knife right now, follow these steps:

- Check for a burr: Run your fingernail (carefully!) down the side of the blade toward the edge. If it catches a "lip" of metal, you're ready to strop.

- Get a flat surface: A piece of denim wrapped around a 2x4 works if you don't have a strop.

- Use the "Trailing" stroke: Pull the blade away from the edge. Keep the spine low.

- Count your reps: Do 10 passes on one side, then 10 on the other. Then 5 and 5. Then 1 and 1.

- The Arm Hair Test: If it shaves cleanly without tugging, you're done. If it doesn't, go back to your finest stone for three passes and try stropping again.

Next time you're watching TV, grab your favorite pocket knife and a piece of cardboard. Practice that trailing-edge motion. It’s meditative, it’s useful, and it ensures that the next time you actually need to cut something, you aren't fighting your tool.

Once you see the mirror-polish an edge takes on after a proper stropping session, you’ll never consider a knife "finished" straight off the stones again. It’s that final 5% of effort that provides 50% of the performance. Check your edge, keep your pressure light, and stop before you round the apex. That’s all there is to it.