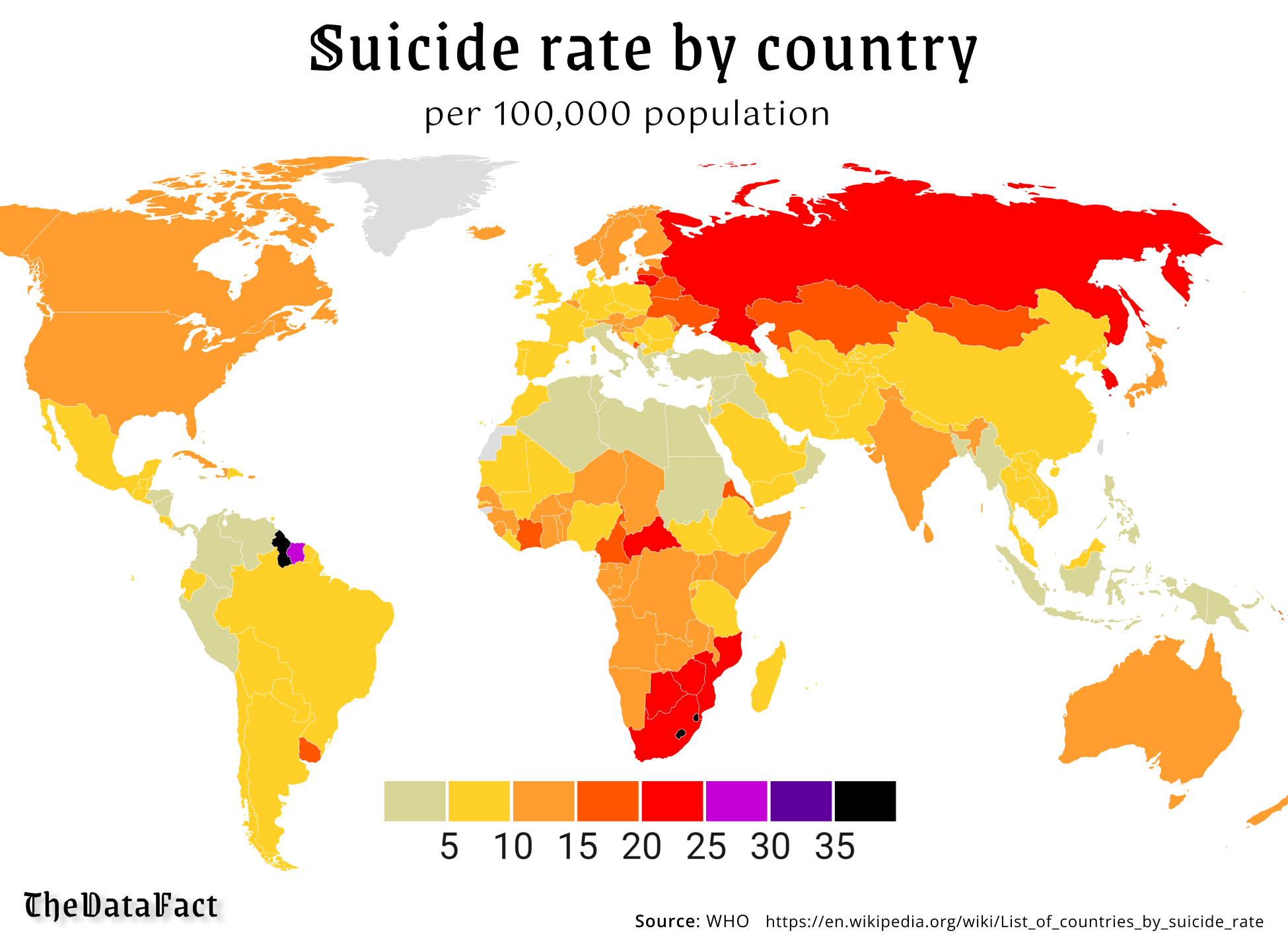

Numbers usually tell a story, but when it comes to the suicide rate by country, those numbers often lie—or at least, they leave out the most important parts. You've probably seen the headlines. One year a certain Baltic nation is at the top, the next it’s a tiny island in the Pacific. Honestly, it’s a lot more complicated than a simple leaderboard.

Every year, more than 720,000 people die by suicide. That’s a staggering figure from the World Health Organization (WHO). It basically means one person every 40 seconds. But those 40 seconds look very different depending on whether you’re in Seoul, Vilnius, or Georgetown.

The Reality Behind the Rankings

If you look at the raw data, Lesotho often sits at the very top of the list. Their reported rate has spiked as high as 87.5 per 100,000 people. That’s huge. But why? In Lesotho’s case, it’s a perfect storm of extreme poverty, one of the highest HIV/AIDS rates in the world, and a lack of mental health infrastructure.

Then you have South Korea. It’s the highest among OECD countries and has been for a long time. They have a rate of about 27.5 per 100,000. It’s a wealthy, high-tech society. So the "poverty equals suicide" theory doesn't always hold water. In Korea, experts like those at the Korea Suicide Prevention Center point to a "pressure cooker" culture. Intense academic competition, the breakdown of the traditional family safety net for the elderly, and the "copycat" effect after celebrity deaths create a unique crisis.

Why the Data is Kinda Messy

Let’s be real: many countries don't want to report these numbers accurately. Suicide is still a crime in some places. In others, it's a massive social taboo.

- Underreporting: A 2025 study in Frontiers in Psychiatry estimated global underreporting at about 17.9%.

- Misclassification: Often, a suicide is recorded as an "accidental poisoning" or "undetermined intent" to save the family from shame.

- Data Quality: Only about 80 WHO member states have what's considered "high-quality" data. If a country doesn't have a good system for tracking any deaths, their suicide stats are basically a guess.

The Gender Paradox

This is one of the weirdest parts of the suicide rate by country. In almost every single nation, men die by suicide at much higher rates than women. Globally, it’s about twice as likely for men. In some places like Lithuania or Russia, the gap is even wider—men might be 4 or 5 times more likely to take their own lives.

But here’s the kicker: women actually attempt suicide more often.

It’s often called the "gender paradox" in suicidal behavior. Men tend to use more violent, "certain" methods. Women are more likely to use methods that allow for intervention, like poisoning. However, in India, this gap is much smaller. In some age groups in India, the female suicide rate is actually higher than the global average for women, often linked to domestic issues and social status transitions.

What’s Happening in High-Income Nations?

You’d think more money would mean better mental health. It doesn't. The United States has seen its rate climb over the last two decades, currently sitting around 14.5 to 15.6 per 100,000.

A lot of people blame "deaths of despair." That’s a term popularized by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton. It refers to the rise in deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease among middle-aged, white, working-class Americans. It’s about a loss of purpose and economic stability.

Then you have the "Nordic Paradox." Countries like Finland and Sweden rank as the happiest in the world, yet their suicide rates aren't the lowest. They aren't the highest either—Finland is around 14.6—but it’s a reminder that happiness rankings and mental health crises are two different things.

The Impact of Easy Access

Methods matter. In the US, firearms are used in over half of all suicides. In rural China and Sri Lanka, it used to be pesticides. When Sri Lanka restricted the most toxic pesticides, their total suicide rate dropped significantly. It didn't just move to another method; people survived.

The Lowest Rates: Real or Paper-Only?

Countries like Jordan, Syria, and many Caribbean nations report incredibly low rates—sometimes less than 1 per 100,000.

- Religious Prohibitions: In many Islamic countries, suicide is a severe sin and highly stigmatized. This leads to massive underreporting.

- Social Integration: Stronger community and family bonds in some cultures act as a protective layer.

- Statistical Gaps: If a country is in the middle of a war (like Syria), tracking individual suicides isn't exactly the top priority for the government.

What We Can Actually Do

Looking at the suicide rate by country shouldn't just be about morbid curiosity. It's about seeing what works.

Lithuania used to have the highest rate in Europe. They didn't just ignore it. They started massive public health campaigns, trained "gatekeepers" like teachers and police to spot signs of distress, and restricted alcohol sales. Their rates have been falling steadily for years.

Actionable Insights for the Future:

✨ Don't miss: Charles Bronson Prison Fitness: What Most People Get Wrong

If you are looking at these trends or worried about someone, the global data suggests a few high-impact moves:

- Secure the environment: If someone is in crisis, removing access to lethal means (like locking up medications or firearms) is the single most effective "first aid" step.

- The 20-minute rule: Most suicidal crises are short-lived. If you can help someone get through the most intense 20 to 60 minutes of an urge, the risk drops significantly.

- Look for the "withdraw": Across all cultures, the most common sign isn't crying; it's pulling away. When someone stops engaging with their usual world, that's the red flag.

- Use the resources: Most countries now have 3-digit or easy-access hotlines (like 988 in the US). These aren't just for people on a bridge; they’re for anyone who feels like they’re drowning.

The global suicide rate is a heavy topic, but the numbers are moving in the right direction in many places. Awareness is higher than it’s ever been. We’re moving away from seeing it as a "personal failure" and toward seeing it as a public health challenge that we can actually solve.

To stay informed or help someone in need, keep a list of local crisis resources on your phone. In the US and Canada, you can call or text 988. In the UK, you can call 111 or contact Samaritans at 116 123. Most countries have dedicated helplines that are free and available 24/7. Taking that small step to know the number can quite literally save a life.