It’s just a painting. Seriously. If you saw it at a yard sale in South Boston, you’d probably keep walking. It’s a bit messy, the colors are dark, and the perspective is… well, it’s not exactly a Da Vinci. But when Sean Maguire (Robin Williams) leans back in his chair and lets Will Hunting (Matt Damon) tear that canvas apart with his words, it becomes one of the most pivotal moments in cinema history.

The painting in Good Will Hunting isn't just a prop. It's a landmine.

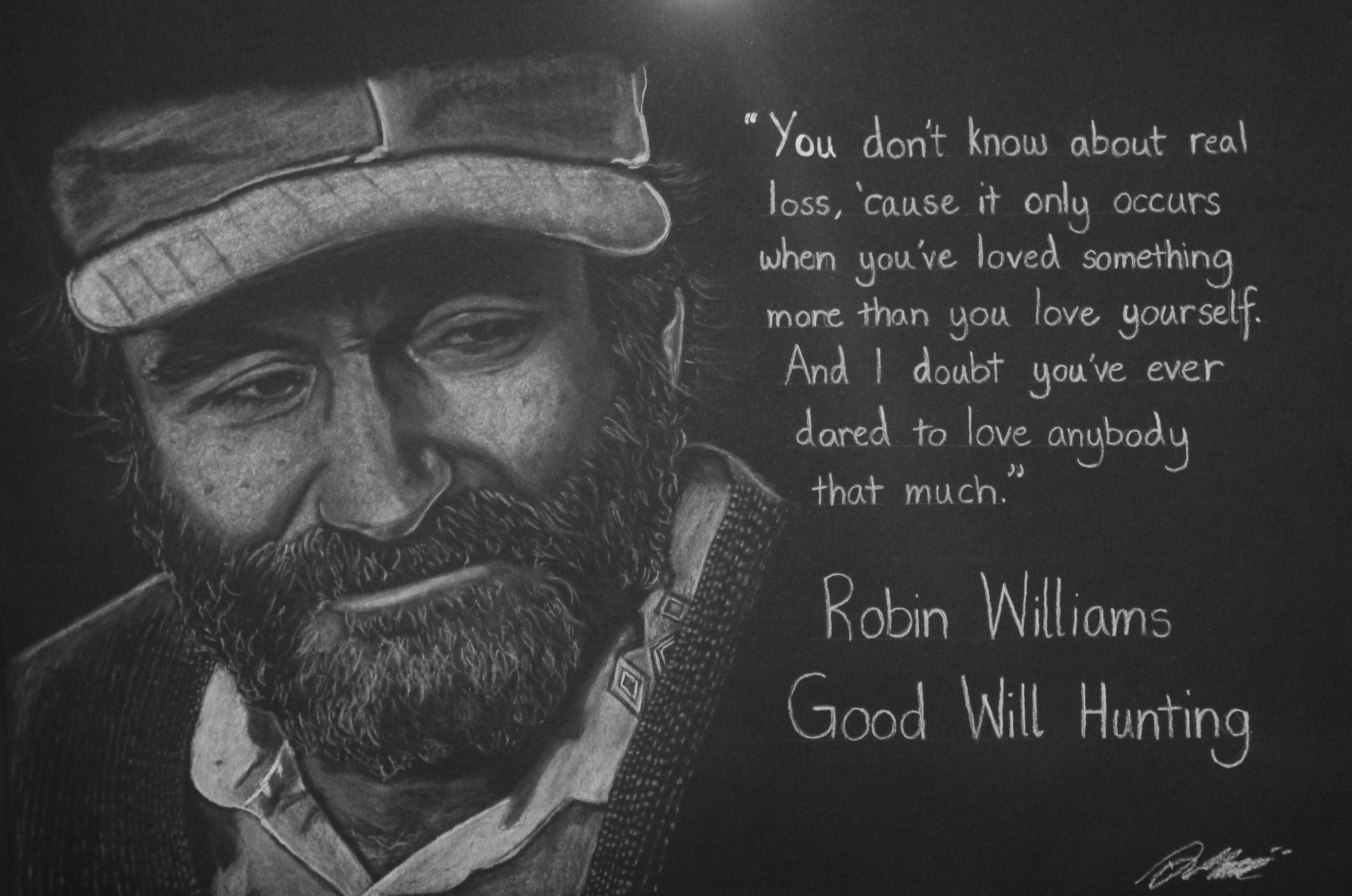

Most people remember the "It’s not your fault" scene as the emotional peak of the movie, and rightfully so. But the groundwork for that breakthrough was laid weeks earlier in Sean's cramped, book-filled office. The moment Will looks at the painting—the one of the lone rower in a storm—everything changes. It’s the first time we see Will's genius used as a defensive weapon against someone who actually understands the pain behind it.

The Story Behind the Canvas

Let’s get the facts straight first. The painting wasn't some high-end gallery piece. It was actually painted by the director himself, Gus Van Sant. This adds a layer of raw, personal energy to the scene. It doesn’t look like "fine art" because it isn't supposed to. It’s supposed to look like the work of a man who is grieving, someone who is stuck in the middle of a psychological tempest and can’t find his way back to shore.

The image depicts a man in a small boat, oars in hand, surrounded by a chaotic, blue-grey sea.

Will stares at it. You can see his brain working, clicking through variables like a supercomputer. He isn't looking at the brushstrokes for their beauty. He’s looking for a vulnerability. And he finds it. He mocks the "linear" nature of the composition. He insults the technique. Then, he goes for the throat. He suggests Sean married the "wrong woman" or that his wife left him because of his obsession with the "storm."

It’s brutal.

The silence that follows is heavy. Sean doesn't yell. He doesn't kick him out—not immediately. He just watches this kid use a piece of art as a scalpel to try and perform surgery on a stranger's soul. It's the moment Sean realizes that Will isn't just a smart-aleck; he's a terrified boy who uses his intellect to keep the world at arm's length.

Why Will’s Critique Was Technically Wrong but Emotionally Right

Will Hunting is a polymath. He can solve the most complex Fourier rearrangements on a chalkboard in the middle of the night, but he doesn't know a thing about the actual experience of life.

When he critiques the painting in Good Will Hunting, he’s doing what he always does: he’s analyzing. He mentions the "starkness of the sky" and the "shitty" watercolor technique. He's trying to prove he's the smartest person in the room. He tries to "read" Sean through the art.

"Maybe you’re in the middle of a storm," Will says. He’s guessing. He’s trying to find the crack in the armor.

The irony? He’s right about the pain, but he’s wrong about the source. He assumes Sean is a failure because the painting looks "unbalanced." He doesn't realize that the imbalance is the point. Art isn't about the math of the golden ratio; it's about the feeling of being half-drowned.

📖 Related: TV Shows With Nico Hiraga: Why You Should Watch Beyond the Skateboarding

Sean’s rebuttal the next day on the park bench is the real "checkmate" moment. He tells Will that he could recite everything ever written about Michelangelo, but he doesn't know what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel. He tells him he could talk about art all day, but he couldn't tell Sean how it feels to wake up next to a woman and feel true joy.

The painting was the bait. Will bit. And Sean used that bite to show Will how little he actually knew about the world.

The Psychological Weight of the "Rowboat"

If you look at the painting through the lens of psychology—which, given the movie's themes, is the only way to look at it—it represents the "internal working model" of attachment theory.

Sean is the rower.

The storm is his grief over his late wife, Nancy.

The boat is his tiny, fragile life.

Will sees the boat and thinks it’s a sign of weakness. He thinks Sean is "circling the drain." But for Sean, the painting is a way of externalizing a feeling that is too big to keep inside. This is a classic therapeutic tool. Sometimes you can’t say "I’m lonely," but you can paint a guy alone in a boat.

There's a reason the painting stays in the office. It sits there behind Sean's desk, a constant reminder of his own stagnation. Will calls it out for being "unoriginal," and in a way, he's right. Grief is unoriginal. It’s the most common human experience there is, yet it feels entirely unique to the person drowning in it.

How the Scene Changed Screenwriting

Before Good Will Hunting, scenes about art in movies were often pretentious. They were about "meaning" and "symbolism" in a way that felt detached from the characters. Matt Damon and Ben Affleck wrote this scene to be a street fight.

It’s a verbal boxing match.

The pacing is incredible. It starts with Will's quiet observation. The camera stays tight on his face. Then the insults start flying. Then the physical tension—Sean grabbing Will by the throat—breaks the intellectual atmosphere. It reminds the audience that for all the talk about math and philosophy, these are two guys from Southie. They lead with their fists when their hearts get poked.

The painting is the catalyst for the most famous monologue in 90s cinema. Without that "shitty" painting, we never get the park bench scene. We never get Sean Maguire's soul-baring speech about the difference between knowledge and experience.

Spotting the Details You Missed

Next time you watch the film, look at how the painting is lit.

💡 You might also like: Taylor Swift on Guitar: Why Her Playing Actually Matters

In the first scene, it’s shrouded in shadows, much like Sean’s personality at the start of the film. He’s guarded. He’s hiding. As the movie progresses and Sean begins to heal—largely thanks to his interactions with Will—the office seems to get brighter.

Also, pay attention to the placement. The painting is positioned so that Will has to look past Sean to see it. It’s literally Sean’s "background." It’s his history. By attacking the painting, Will is attacking Sean’s past, and Sean’s reaction is the first time anyone has ever stood their ground against Will’s intellectual bullying.

It's also worth noting that the painting isn't "good" by traditional standards. If it were a masterpiece, Will’s critique wouldn't work as well. The fact that it’s an amateurish, emotional outpouring makes Will’s "expert" analysis look even more cold and detached. He’s treating a man’s soul like a textbook.

The Legacy of the Storm

Even decades later, fans still search for prints of the painting in Good Will Hunting. People want it on their walls. Why? Because it represents the moment we stop pretending to be okay.

It’s a symbol of the "messy middle." We aren't always winning, and we aren't always sinking; sometimes we’re just rowing like hell in the middle of a dark ocean, hoping the weather breaks.

The painting teaches us that you can’t analyze your way out of a feeling. You can know the physics of water tension, the chemistry of oil paint, and the history of maritime art, but none of that helps you stay afloat when your wife dies or when your father hurts you.

Lessons From the Canvas

If you're looking to apply the "Sean Maguire" philosophy to your own life or your own creative work, there are a few things to take away from this specific piece of movie history:

- Experience Trumps Information: You can read every book on a subject, but until you’ve lived it, you’re just a "smart-ass kid" (in Sean’s words). Don't mistake data for wisdom.

- Vulnerability is a Mirror: Will attacked the painting because he saw his own isolation reflected in the rower. When someone lashes out at your "art" or your work, they are often just reacting to their own insecurities.

- Art Doesn't Have to Be Perfect to Be Powerful: The "storm" painting was technically flawed, yet it sparked the most important conversation in the characters' lives. Don't let the fear of being "unoriginal" stop you from expressing something real.

- Watch for the "Defense Mechanisms": Will’s use of art history to deflect from his own trauma is a classic example of "intellectualization." Recognize when you are using your skills to hide your heart.

The painting in Good Will Hunting eventually disappears from the narrative as the two men move toward actual healing. Once the truth is out in the open, the metaphor isn't needed anymore. Will doesn't need to mock it, and Sean doesn't need to hide behind it. They eventually just become two men, sitting in a room, finally talking for real.

Next Steps for Fans and Creators:

- Re-watch the scene: Focus entirely on Sean's face while Will is talking. Robin Williams' performance in those silent moments is a masterclass in controlled pain.

- Explore Gus Van Sant’s Art: If you liked the raw style of the painting, check out Van Sant’s photography and other paintings. He has a very specific, lo-fi aesthetic that influenced the entire look of the film.

- Practice "Active Observation": The next time you see a piece of art you don't "get," try to avoid the Will Hunting trap. Don't look for what’s wrong with it. Ask yourself what the person who made it was trying to survive.

Art isn't a puzzle to be solved. It’s a bridge to be crossed. Will Hunting finally crossed it when he stopped looking at the paint and started looking at the man who held the brush.