You probably won't find one in your Christmas card this year. Honestly, most people go their entire lives without seeing a US 1000 dollar bill in the flesh, and there's a good reason for that. They haven't been printed in eighty years. But if you happened to stumble upon one in a dusty attic or an old safe-deposit box, don't just run to the bank and deposit it for face value. You'd be losing a small fortune.

It's a weird piece of American history. Most folks assume that anything higher than a hundred-dollar bill is either Monopoly money or a total fake. They’re wrong. These things are very real, they are absolutely legal tender, and they carry the face of a guy who wasn't even a President. Alexander Hamilton? No, he’s on the ten. We’re talking about Grover Cleveland.

What’s the Deal With the $1,000 Bill?

Technically, the US 1000 dollar bill is still "live" money. You could, in theory, walk into a 7-Eleven, grab a Slurpee, and hand the clerk a Series 1934 gold certificate. They would probably call the cops. Then the cops would probably call the Secret Service. It would be a whole thing. But at the end of the day, the government still recognizes these notes as valid currency.

The Federal Reserve stopped printing them in 1945. They officially "retired" the high-denomination notes in 1969. Why? Because nobody was using them for groceries. They were being used by the mob. When you’re trying to move a million dollars in cash, it’s a lot easier to carry a stack of thousands than a suitcase full of twenties. To curb money laundering and organized crime, the Nixon administration decided to keep the $100 bill as the largest note in circulation.

Since then, the Fed has been on a "find and destroy" mission. Every time a $1,000 bill hits a bank, it’s supposed to be sent back to the Treasury to be shredded. This makes them incredibly rare. There are only about 165,000 of the 1934 series still floating around in the wild.

The Varieties of the US 1000 Dollar Bill

Not all of these notes are created equal. If you're looking at one, the first thing you need to check is the seal.

Most of the ones that survived are the Series 1928 or 1934 Federal Reserve Notes. These feature Grover Cleveland’s portrait. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms, which is a fun trivia fact, but in the world of paper money, he’s just the "thousand-dollar guy."

But then there are the Gold Certificates.

Back in the day, you could actually trade your paper money for physical gold. These notes have a distinct orange/gold reverse side and a bright gold seal. They are stunning. If you have a 1928 Gold Certificate US 1000 dollar bill, you aren't just looking at a piece of history; you're looking at a down payment on a house. Collectors go absolutely nuts for these because the color is so vibrant and the historical context of the Gold Standard is so heavy.

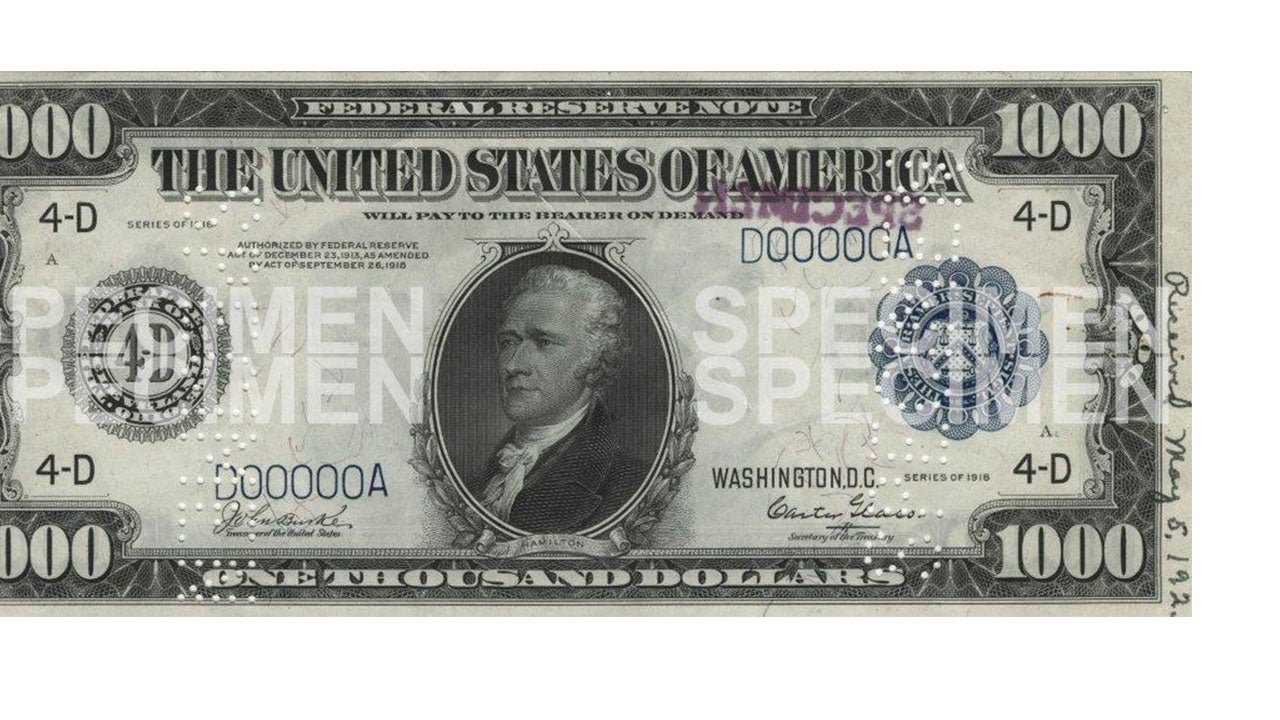

Then you have the Series 1918 Blue Seals. These are large-size notes, often called "horse blankets" because they are significantly bigger than the money we use today. They feature Alexander Hamilton. Wait, I thought I said Cleveland? On the 1918 series, it was Hamilton. The Treasury changed the portraits when they shrunk the physical size of the bills in 1928.

Why the Price Varies So Much

Condition is everything. In the numismatic world, we talk about "grading." A bill that looks like it was crumpled in someone's pocket for a decade might only be worth $1,500 to $2,000. That’s still a profit, sure.

But a "Gem Uncirculated" note? That’s a different story.

I’ve seen pristine 1934 $1,000 bills go for $5,000 or $8,000 at auction. If the serial number is interesting—like 00000001 or a "radar" number that reads the same backward and forward—the price can jump into the tens of thousands.

There's also the "Star Note" factor. If there is a little star next to the serial number, it means the bill was a replacement for a sheet that was misprinted. These are much rarer. A 1934 $1,000 Star Note is basically the Holy Grail for some collectors.

Is It Actually Legal to Own One?

Yes. 100%.

🔗 Read more: Coal India share value: What Most People Get Wrong About This Dividend Giant

There was a brief period where the government made it tricky to hold certain gold-related currencies, but today, owning a US 1000 dollar bill is perfectly legal. You don't need a special permit. You don't need to report it to the FBI. You just need to have the cash to buy one.

The real danger isn't the law; it's the fakes.

Counterfeiting high-value notes was a massive problem in the early 20th century. Also, modern scammers love to take a $1 bill and "wash" it, printing a fake $1,000 image over the top. If you're buying one, you have to look for the security features of the era. Look at the paper. Real US currency is printed on paper that is actually a blend of linen and cotton. It shouldn't feel like a printed photo. It should have tiny red and blue silk fibers embedded in the paper itself.

Where to Find Them (And How to Sell Them)

You aren't going to find these at the local bank. Trust me, I've asked. Tellers will just look at you like you've lost your mind.

If you want to buy a US 1000 dollar bill, you need to go through reputable auction houses like Heritage Auctions or Stack’s Bowers. These places verify the authenticity and the grade of the note. They use third-party grading services like PCGS (Professional Coin Grading Service) or PMG (Paper Money Guaranty).

If a bill is "slabbed"—encased in a hard plastic holder with a certified grade—it's worth significantly more because the buyer knows exactly what they’re getting.

If you happen to inherit one, please, for the love of all things holy, do not take it to a pawn shop. Most pawn shop owners are looking to flip items quickly and will offer you maybe 60% of the actual value. You’re better off reaching out to a dedicated currency dealer or putting it up for a specialized numismatic auction.

The Future of High-Denomination Currency

Will we ever see a new US 1000 dollar bill?

Probably not. In fact, there's a lot of political pressure right now to get rid of the $100 bill. Economic experts like Larry Summers have argued that large bills only help criminals and tax evaders. As we move closer to a digital economy, the need for physical "big money" is shrinking.

But that's exactly why the old ones keep going up in value. They represent a time when money was physical, heavy, and meant something different. They are artifacts.

Actionable Steps if You Find or Want a $1,000 Bill

- Check the Seal Color: Green is common (Federal Reserve Note), Gold is rare (Gold Certificate), Blue is very old and very valuable (1918 series).

- Examine the Borders: Look for any tears or "pinholes." People used to pin cash to the inside of their coats to prevent theft. Those tiny holes can drop the value by hundreds of dollars.

- Get it Graded: If the bill looks crisp and uncirculated, send it to PMG. A certified grade of 65 or higher can double the market price.

- Never Clean It: This is the golden rule of collectibles. Do not iron it. Do not use bleach. Do not try to "freshen it up." You will destroy the microscopic fibers of the paper and tank the value instantly.

- Storage Matters: If you own one, keep it in a PVC-free plastic sleeve. Regular plastic can "outgas" and turn the paper yellow or brittle over time.

The US 1000 dollar bill is a ghost in the American financial system. It’s there, but it’s not. It’s worth exactly $1,000 at the bank, but it’s worth $4,000 to the guy across the street. In a world of digital bits and credit scores, there’s something deeply satisfying about holding a piece of paper that says the United States of America owes you a thousand dollars. Just don't spend it on a Slurpee.