Five years. That is how long the United States had been "back together" when the 1870 census hit. But if you look at an 1870 map of us, you aren't looking at a finished product. Far from it. Honestly, you’re looking at a giant work in progress that looks kinda like a half-baked cake.

The Civil War was over, but the dirt hadn't even settled. People were moving. Like, really moving. If you lived in 1870, the map was shifting under your feet because the federal government was carving out territories faster than they could survey them. You’ve got these massive blocks of land out West—places like the Dakota Territory—that hadn't been broken down into the states we know today. It’s chaotic. It’s messy. And it is the most honest snapshot of a country trying to find its new shape after literally almost tearing itself in two.

What an 1870 map of us actually reveals about a broken nation

When you first glance at a map from this era, your eyes probably go straight to the West. That’s where the "empty" spots are. But the real story is in the South and the East.

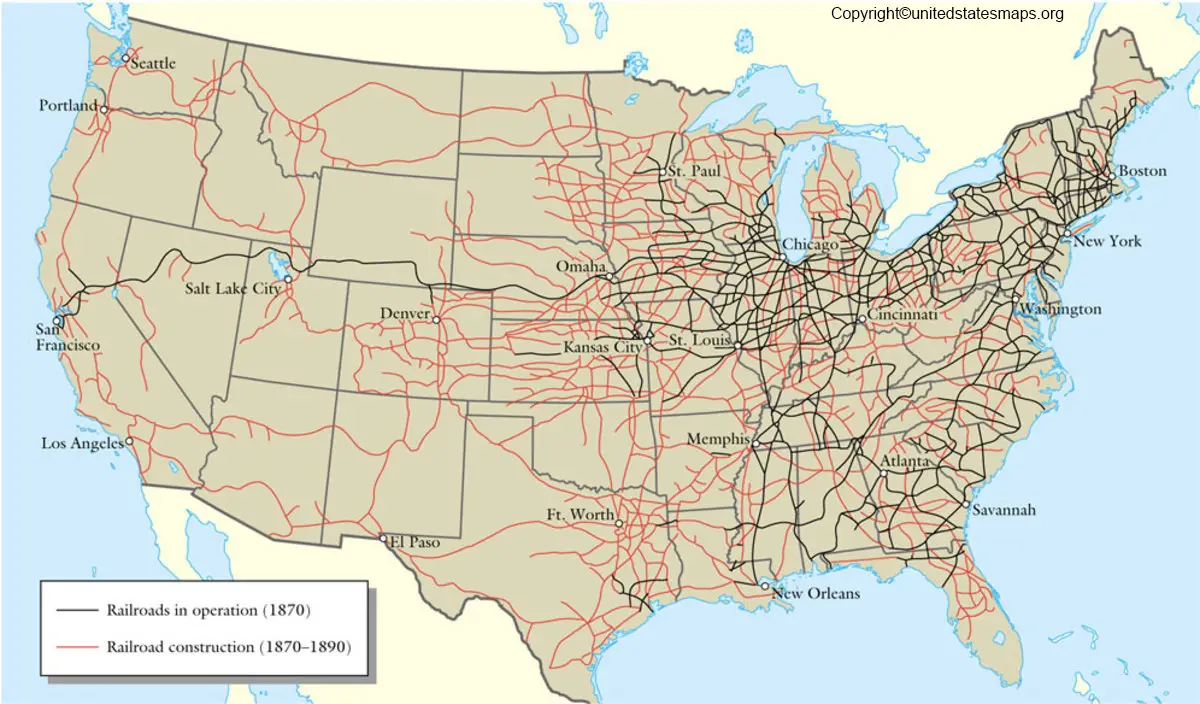

In 1870, the "United States" was technically united, sure. But the map doesn't show you the military districts or the Reconstruction-era tension. What it does show is the sudden, explosive growth of the railroad. Look at the lines. By 1870, the First Transcontinental Railroad had been finished for about a year. Suddenly, an 1870 map of us wasn't just about borders; it was about the iron veins connecting New York to San Francisco.

🔗 Read more: Por qué el degradado corte en v hombre atras es la técnica que define la barbería moderna

The phantom borders of the West

Ever notice how Wyoming looks like a perfect rectangle? That happened in 1868, just two years before this map era. But look at the Dakota Territory. In 1870, it was one giant blob. It wouldn't split into North and South for another nineteen years. If you were a settler moving there, you weren't "moving to North Dakota." You were just going to the "Dakotas."

The map was a liar, too. It showed clear boundaries, but for the Indigenous populations—the Sioux, the Cheyenne, the Apache—those lines were foreign impositions. The 1870 map marks a period of intense conflict. It represents the blueprint for the reservation system that was being aggressively forced upon the landscape.

Why the 1870 census changed how maps were drawn

We have to talk about Francis Amasa Walker. He was the superintendent of the 1870 Census, and the guy was basically a data nerd before that was a thing. He realized that a basic map showing state lines was boring and, frankly, useless for a growing empire.

So, he helped create the Statistical Atlas of the United States. This changed everything. For the first time, an 1870 map of us could show you where people lived, not just where the dirt was. It showed population density using "choropleth" shading—you know, the darker the color, the more people.

It showed something else kind of shocking for the time: the "Frontier Line."

This was a literal line on the map. If an area had fewer than two people per square mile, it was "unsettled." In 1870, that line was jagged and weird. It poked into Kansas and Nebraska. It retreated in the face of the Rocky Mountains. Seeing this on paper made Americans realize that the "Wild West" was actually shrinking. It turned the map into a countdown clock.

The ghost of the Confederacy

Look at the state lines in the South. They look the same as 1860, right? Physically, yes. But the 1870 map is the first one where the "Three-Fifths Compromise" is gone. Every single person on that map was now, legally, a full person for representation.

🔗 Read more: Why Christian Quotes for Thanksgiving Still Matter in a Busy World

This shifted the political weight of the map entirely. Even if the borders didn't move an inch, the power inside those borders was supposed to be fundamentally different. Maps from this year were often used by politicians to figure out how to gerrymander new districts to account for the millions of newly enfranchised Black citizens. It was a map of hope and a map of deep, systemic resistance.

Decoding the tiny details most people miss

If you find an original lithograph or a high-res scan from the Library of Congress, stop looking at the big names. Look at the corners.

- The Railway Hubs: See how Chicago looks like a spider? In 1870, it was the gateway. Everything went through Chicago.

- The "Unorganized" Territories: Look at what is now Oklahoma. It's often labeled "Indian Territory." It’s a somber reminder of the forced relocations that defined the mid-19th century.

- The Names That Died: You’ll see towns on an 1870 map of us that don’t exist anymore. Mining towns in Nevada or Colorado that boomed for six months and then turned to dust.

It’s also worth noting that the 1870 map was the last time the US felt truly "regional." Within a few decades, the telegraph and the rail would make the country feel much smaller. But in 1870? If you were in Maine, Oregon might as well have been the moon.

The technology of the 1870 map

They weren't using satellites, obviously. They were using "plane table" surveying and theodolites. It was grueling work. Men lugged heavy brass instruments up mountains to get the angles right.

This is why, if you look closely at an 1870 map of us, the mountains often look like hairy caterpillars. That’s "hachuring." It was the old-school way of showing elevation before we got good at contour lines. It gives the map a hand-drawn, organic feel that modern Google Maps just can’t touch. It feels alive.

How to use an 1870 map for your own research

Whether you are a genealogy buff or just a history nerd, these maps are gold mines. But you have to know which one you’re looking at. There isn't just "one" map.

💡 You might also like: My Life as Eva: Why the Original Lifestyle Influencer Era Actually Matters

There are Postal Route Maps, which are incredible if you want to know how long it took a letter to get from St. Louis to Denver. There are Railroad Guide Maps, which are basically the 19th-century version of an airline app. Then there are the General Land Office (GLO) maps, which show exactly who was buying what plot of dirt.

Real-world steps for the map hunter

If you want to dive into this properly, don't just search Google Images. You’ll get low-quality junk.

Go to the David Rumsey Map Collection. It is arguably the best digital map archive on the planet. You can overlay an 1870 map of us directly on top of a modern 2026 satellite view. It is trippy. You can see your own neighborhood and realize that in 1870, it was maybe just a cow pasture or a dense forest owned by a railroad company.

Another move? Check the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. They have the high-resolution TIF files. You can zoom in until you see the individual ink bleeds on the paper.

Why you should care about 1870 specifically

1870 is the "hinge" year.

The 1850s were about the lead-up to war.

The 1860s were the war itself.

The 1880s were the Gilded Age.

1870? 1870 is the awkward teenage years of America. It’s the moment the country decided it was going to be an industrial powerhouse, but it still had one foot in the frontier mud.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly understand the 1870 landscape, start by identifying a specific location—perhaps your hometown or a family ancestral site. Access the David Rumsey Map Collection and use the "Georeferencer" tool to compare the 1870 layout with modern roads.

Focus on identifying:

- The nearest rail line: If there wasn't one within 20 miles in 1870, that area was likely economically isolated.

- The county boundaries: Many counties were much larger in 1870 and were later subdivided; this is crucial for tracking down old property deeds or census records.

- Water sources: Note the proximity to rivers, as these remained the primary "highways" for heavy goods before the rail network was fully integrated.

By narrowing your focus from the national level to a specific county, the abstract lines of the 1870 map of us become a tangible history of how the land was actually used and lived upon.