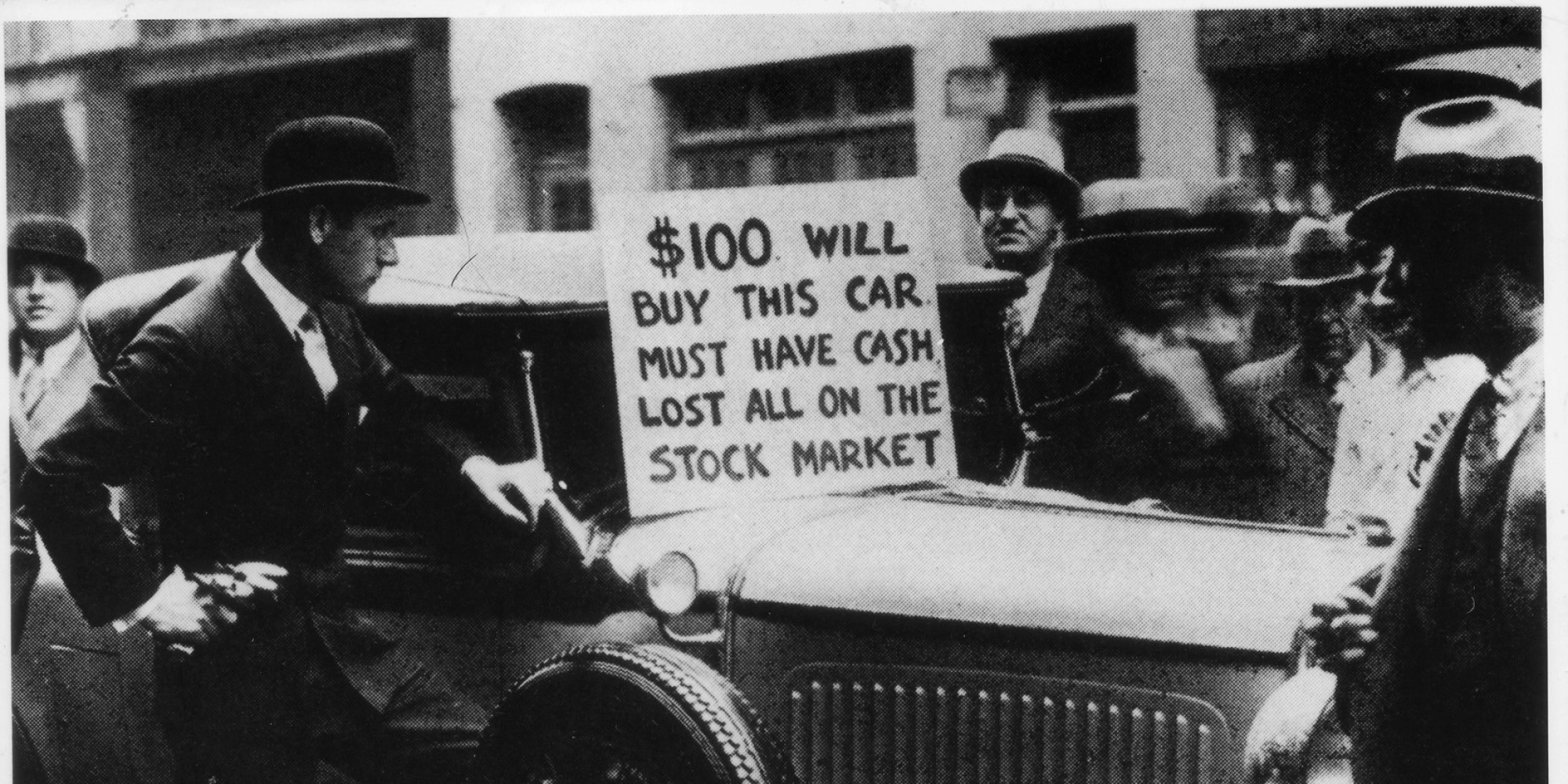

Everyone thinks they know how the 1929 stock market crash went down. They picture brokers leaping from skyscrapers and the entire world turning gray overnight. It's a cinematic image. But honestly? Much of that is just myth-making and historical shorthand that misses the actual, messy reality of what happened on Wall Street during those frantic weeks in October.

The market didn't just fall off a cliff in a single afternoon. It was a slow-motion car wreck.

In the late 1920s, the United States was obsessed with the market. You had "shoe-shine boys" giving stock tips—a classic trope, sure, but it pointed to a real phenomenon of mass participation. People weren't just investing; they were gambling with money they didn't have. This was the era of "buying on margin." Basically, you could put down just 10% of a stock's price, and your broker would lend you the rest. It works great when prices go up. When they don't, things get ugly fast.

The Myth of the "Great Leap" and the Real Timeline

Let's clear one thing up: there wasn't a wave of bankers jumping out of windows on Black Tuesday. That's a legend. Winston Churchill was actually in New York at the time, staying at the Savoy-Plaza, and he did see one person fall to their death, but it wasn't a prominent financier. The suicide rate in New York actually stayed relatively stable that month.

The 1929 stock market crash was a series of tremors, not one big earthquake.

First came Black Thursday, October 24. The market opened shaky. By mid-morning, prices were cratering. A group of powerful bankers, including Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan and Charles E. Mitchell of National City Bank, met to try and save the day. They pooled their money and started buying shares of U.S. Steel above market price to show confidence. It worked—sort of. The market recovered a bit. People breathed a sigh of relief over the weekend. They thought the "organized support" had saved them.

They were wrong.

Monday, October 28, was a bloodbath. Then came the infamous Black Tuesday, October 29. On that single day, the market lost about 12%. Panic wasn't just a word; it was a physical force on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. The ticker tape machines, which printed stock prices, couldn't keep up. They were hours behind. Investors were selling stocks without even knowing what the current price was. Imagine trying to trade on an app today where the prices are from three hours ago. You'd lose your mind.

Why Did the Bottom Fall Out?

It's easy to blame "greed," but that's a lazy answer. The structure of the market was fundamentally broken.

Economists like John Kenneth Galbraith, who wrote the definitive The Great Crash, 1929, pointed to a few specific structural failures. First, there was the "Investment Trust" craze. These were basically the 1920s version of mutual funds, but with zero regulation and tons of leverage. They were often "pyramids" where one trust owned shares in another trust, which owned shares in another. When the base crumbled, the whole thing folded like a cheap card table.

Then you had the lopsided distribution of wealth. The 1920s were roaring for the rich, but wages for workers were largely stagnant while productivity skyrocketed. People couldn't afford to buy the stuff they were making.

The Margin Call Nightmare

If you bought $10,000 worth of Radio Corporation of America (RCA) stock with only $1,000 of your own money, you felt like a genius in 1928. RCA was the Nvidia of its day. But when the price dropped even slightly, your broker would call you up—a margin call—and demand more cash immediately to cover the loan.

If you didn't have the cash? The broker sold your stock.

This created a feedback loop. Prices drop -> Margin calls happen -> People sell to get cash -> Prices drop further -> More margin calls. It was a self-destruct mechanism built into the very fabric of the exchange. By the time the 1929 stock market crash reached its nadir, billions of dollars in "wealth" had simply vanished. It wasn't "transferred" to anyone else. It just ceased to exist.

The Fed and the Great Oops

Could the Federal Reserve have stopped it?

Modern economists like Milton Friedman and even former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke argued that the Fed actually made things worse. They were worried about "speculation," so they raised interest rates in 1928 and 1929 to try and cool the market down. It was like trying to put out a grease fire with a bucket of water.

The higher rates didn't stop the speculators, but they did hurt the real economy. They made it harder for farmers to get loans and for businesses to expand. By the time the crash actually hit, the economy was already weakening. The Fed then stayed too tight for too long, failing to act as a "lender of last resort." They let banks fail by the thousands.

This Wasn't Just a "Wall Street" Problem

People often think the crash caused the Great Depression. That's not entirely accurate. The crash was a major catalyst, sure, but the Depression was a result of many things: bad trade policies (like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act), a collapsing banking system, and a devastating drought in the Midwest.

However, the 1929 stock market crash destroyed the one thing an economy needs to function: confidence.

Before the crash, people believed the "New Era" was here. They thought poverty was going to be abolished. After October 1929, that optimism was replaced by a deep, soul-crushing fear. People stopped spending. They stopped investing. They pulled their money out of banks and hid it under mattresses.

💡 You might also like: India Gold Rate Today in Hyderabad: Why the City of Pearls is Seeing Record Highs

What We Learned (and What We Forgot)

The aftermath of the crash gave us the modern financial world.

We got the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 because, before that, companies could basically lie about their earnings with zero consequences. We got the Glass-Steagall Act, which forced a divorce between "boring" commercial banking (checking accounts) and "risky" investment banking. We got FDIC insurance so that if your bank goes bust, you don't lose your life savings.

But humans have short memories.

Every few decades, we start to think we've "solved" the market. We saw echoes of 1929 in the Dot-com bubble of 2000 and the Great Recession of 2008. The specific "tech" changes—from ticker tapes to high-frequency trading algorithms—don't change the underlying psychology of fear and greed.

Actionable Lessons for Today's Investors

You don't need to be a history buff to protect your portfolio. Here is the "too long; didn't read" version of how to not get wiped out like a 1929 speculator:

- Check your leverage. If you are trading on margin or using high-leverage options, you are playing the exact same game that ruined people in 1929. One bad week can wipe you out completely.

- Diversification is your only hedge against "systemic" failure. In 1929, the people who survived were the ones who didn't have 100% of their net worth in speculative stocks. They had cash, they had bonds, and they had diverse assets.

- Don't trust the "New Era" talk. Whenever you hear someone say "the old rules of economics don't apply anymore because of [AI/Crypto/The Internet]," that is your signal to get cautious. The rules always apply eventually.

- Watch the Fed, but don't worship them. Central banks are run by humans. They make mistakes. They can be too slow to cut rates or too fast to raise them. Always have a "plan B" for your finances that doesn't rely on a perfect economic "soft landing."

The 1929 stock market crash wasn't just a historical event. It was a masterclass in human psychology and the dangers of unregulated exuberance. The market eventually recovered, but it took 25 years for the Dow Jones Industrial Average to get back to its 1929 peak. Twenty-five years. That's a whole generation of lost growth.

👉 See also: Dow Industrial Average Graph: What Most People Get Wrong

Understanding what really happened helps you see through the noise of today's market cycles. It's not about being a "doomer"; it's about being a realist. The ghosts of 1929 are still wandering around Wall Street, reminding us that what goes up can come down—and it usually comes down much faster than it went up.

Stop looking for the "next big thing" for five minutes and look at your risk exposure. That's the best way to honor the hard-learned lessons of October 1929. Be the person who stays calm when everyone else is staring at a lagging ticker tape in a panic.