You know that feeling when you're watching a movie and suddenly the air just leaves the room? That’s S. Craig Zahler’s calling card. If you’ve seen it, you know exactly what I’m talking about. The Bone Tomahawk split scene isn't just a moment of movie gore; it’s a cultural scar for horror and western fans alike. It’s the kind of thing that makes you want to look away, but your eyes are basically glued to the screen in a sort of horrified trance.

Westerns used to be about the hero riding into the sunset. They were clean. Even the gritty ones from the 70s had a certain "movie-ness" to them. But then 2015 happened. Zahler dropped this low-budget, slow-burn masterpiece that felt like a traditional John Wayne flick for the first eighty minutes, only to turn into a literal nightmare in the final act. People weren't ready. Honestly, I don't think anyone is ever truly ready for what happens to Deputy Nick in that cave.

The Brutality of the Bone Tomahawk Split Scene

Let's get into the weeds of why this specific moment works so well—or why it’s so traumatizing, depending on how you look at it. Most horror movies use "movie magic" sounds. You hear a "squish" or a "thud" that sounds like a watermelon hitting pavement. Zahler didn't do that. The sound design in the Bone Tomahawk split scene is dry. It’s crunchy. It sounds like wood snapping, which is infinitely more upsetting because your brain recognizes that sound as something real.

The scene involves a character being stripped, flipped upside down, and... well, the title of the scene doesn't leave much to the imagination. The Troglodytes—the "clansmen" who aren't quite human but definitely aren't supernatural—handle the human body like a piece of livestock. That’s the kicker. There’s no malice in their eyes. There’s no "evil villain" monologue. It’s just a Tuesday for them. They are hungry, and the Deputy is meat.

The cinematography stays wide. That's a huge factor. Usually, directors cut away or use shaky cam to hide the practical effects. Here? Benji Bakshi, the cinematographer, keeps the camera steady. You see the whole thing. You see the internal logic of the violence. It’s clinical. It feels like a National Geographic documentary filmed in hell. Kurt Russell’s character, Sheriff Hunt, has to watch it all from a cage. His reaction—that mixture of pure shock and a desperate need to maintain some kind of authority—is what grounds the horror. It’s not just about the blood; it’s about the total loss of human dignity.

Why This Scene Changed the "Weird Western" Genre

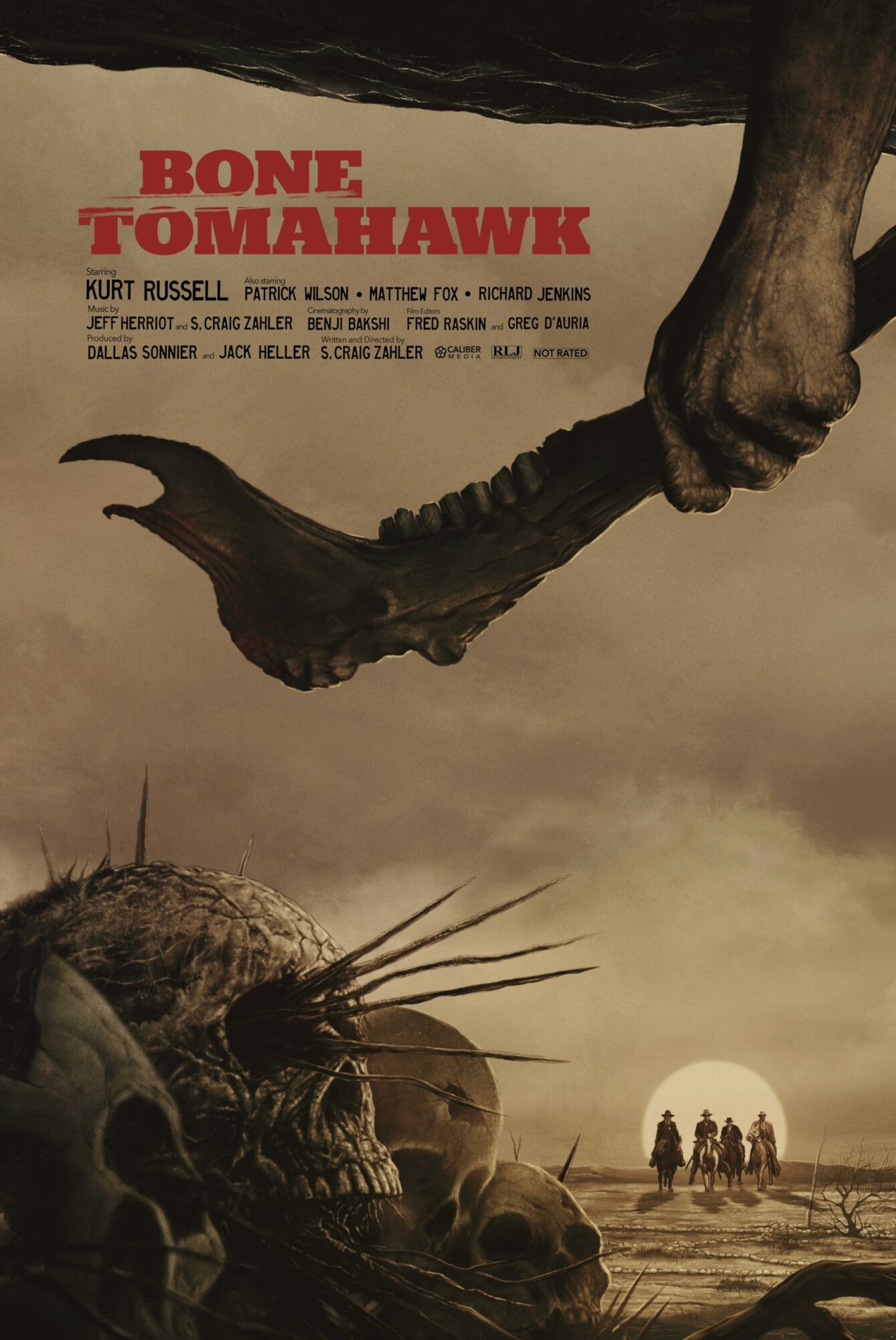

Before this movie, the "Weird Western" was a niche subgenre that mostly lived in comic books or straight-to-DVD bargains. Bone Tomahawk changed the math. It proved that you could have high-level acting—we're talking Patrick Wilson, Matthew Fox, and Richard Jenkins—and still go "full grindhouse."

The Bone Tomahawk split scene serves as a hard pivot point. Up until that moment, the movie is a talky, character-driven journey. You grow to love these guys. Chicory, played by Richard Jenkins, is one of the most endearing characters in modern cinema. He’s a bumbling, kind-hearted old man. Putting characters like that in a world where the "split scene" is possible creates a level of tension that’s almost unbearable. You realize that "plot armor" doesn't exist in Zahler’s world.

Critics like Mark Kermode have noted that the film's strength lies in its patience. It builds a bridge of empathy for an hour and a half, then blows that bridge up with a stick of dynamite made of human bone. It’s a subversion of the "cavalry comes to the rescue" trope. In this movie, the cavalry arrives, gets captured, and gets bifurcated.

The Practical Effects Behind the Mayhem

If you’re a gearhead or a practical effects nerd, you have to respect what the makeup team did here. In an era where CGI blood looks like strawberry jam, the physical props used in the Bone Tomahawk split scene are terrifyingly realistic. They used a combination of silicon prosthetics and weighted dummies to simulate the gravity of a human body being hauled around.

When the actual "split" happens, the resistance of the material matters. It doesn't just pop apart. It stretches. It tears. It’s a slow process. This wasn't a high-budget Marvel movie; they had to make every dollar count. By focusing on the mechanical reality of the violence, they created something that looks more "real" than a $200 million blockbuster.

Psychological Impact and the Audience Reaction

I remember seeing this in a small theater. When the scene finished, nobody moved. Nobody even crunched their popcorn. It was total silence. That’s the power of the Bone Tomahawk split scene. It’s a sensory assault that forces you to acknowledge the fragility of the human form.

Some people hate it. They think it’s gratuitous. And hey, that’s a fair take. If you’re looking for a fun Saturday night movie, this ain't it. But for those who appreciate the "frontier" as a place of lawless, primordial terror, it’s a masterclass. It taps into a very primal fear of being consumed—not just eaten, but totally dismantled by something that doesn't share your language or your morals.

The Troglodytes themselves are a fascinating choice. By making them a lost, inbred tribe that uses bone implants in their own throats to make those haunting whistling sounds, Zahler removes the possibility of reasoning with them. You can't talk your way out of the split. You can't offer them gold. They don't want your money. They want your marrow.

Beyond the Gore: The Moral Weight

What really sticks with me isn't just the blood. It’s the way the characters handle the aftermath. Sheriff Hunt is shot, weakened, and has just witnessed his deputy being treated like a side of beef. Yet, he continues. The "split scene" isn't the end of the movie; it’s the catalyst for the final stand.

It highlights the theme of duty. These men knew they were probably going to die. They went anyway. The horror makes their bravery mean more. If the villains were just guys in black hats who missed every shot, the heroes' journey would be cheap. Because the threat is so visceral and so capable of doing that to a human body, the fact that Arthur O'Dwyer (Patrick Wilson) crawls across the desert on a broken leg to save his wife becomes legendary.

Comparisons to Cannibal Holocaust and The Searchers

Film historians often compare Bone Tomahawk to two very different movies: The Searchers and Cannibal Holocaust. It has the DNA of a classic John Ford western—the kidnapping, the long trek, the rugged landscape—but it injects the "video nasty" energy of the late 70s Italian cannibal films.

The Bone Tomahawk split scene is the bridge between those two worlds. It’s where the noble western meets the nihilistic horror. Most movies try to balance these things and fail. They either become too campy or too depressing. Zahler hits a sweet spot where the stakes feel ancient and the violence feels modern.

🔗 Read more: Ben Rathbun and Mahogany Roca: The Tragic Reality Behind the 90 Day Fiancé Mystery

Actionable Insights for Horror Fans and Filmmakers

If you're looking to dive deeper into this kind of cinema, or if you're a creator trying to understand why this scene worked, here are a few things to chew on:

- Pace is everything. The reason the split scene hits so hard is that the movie takes its time. You have to earn the gore. If the movie started with that scene, you wouldn't care. You care because you spent 90 minutes walking through the dirt with Nick.

- Sound over visuals. If you watch the scene on mute, it’s still gross, but it loses 50% of its power. The "wet" sounds of the bone being worked on are what trigger the gag reflex.

- Practical beats digital. Every single time. The weight of a physical prop reacting to gravity creates a sense of "presence" that a digital model can't replicate.

- The "Uncanny Valley" of Violence. The most effective horror isn't always the most fantastical. It’s the violence that feels like it could actually happen in a garage or a butcher shop.

The Bone Tomahawk split scene remains a benchmark for practical effects and tonal shifts in modern cinema. It’s not for everyone—honestly, it’s barely for anyone—but it’s an undeniable piece of filmmaking that refuses to be forgotten. If you’re going to watch it for the first time, maybe skip the snacks. You’ve been warned.

To truly understand the impact of the film, look into S. Craig Zahler's follow-up works, Brawl in Cell Block 99 and Dragged Across Concrete. He continues to explore the idea of the "shattering moment"—a single scene of extreme, grounded violence that redefines the entire narrative. In Brawl, it's the "face scrape." In Bone Tomahawk, it's the split. These aren't just stunts; they are the logical, albeit horrific, conclusions of the worlds these characters inhabit.

Watch the film with an eye on the background characters. Notice how the Troglodytes interact with each other during the scene. There is a hierarchy and a process. It’s that attention to detail—the idea that this horror is a "culture" to those performing it—that makes the scene linger in the mind long after the credits roll. It turns a "slasher" moment into a study of anthropological terror.