It was the late seventies. Lee Strobel was, by all accounts, a rising star at the Chicago Tribune. He was the legal affairs editor, a guy who lived for hard evidence, court transcripts, and the "just the facts" vibe of a gritty newsroom. He was also a committed atheist. He didn't just doubt God; he basically thought religion was a crutch for people who couldn't handle reality. Then his wife, Leslie, became a Christian. For Strobel, this was a disaster. He felt like he was losing the woman he married to a cult or a delusion.

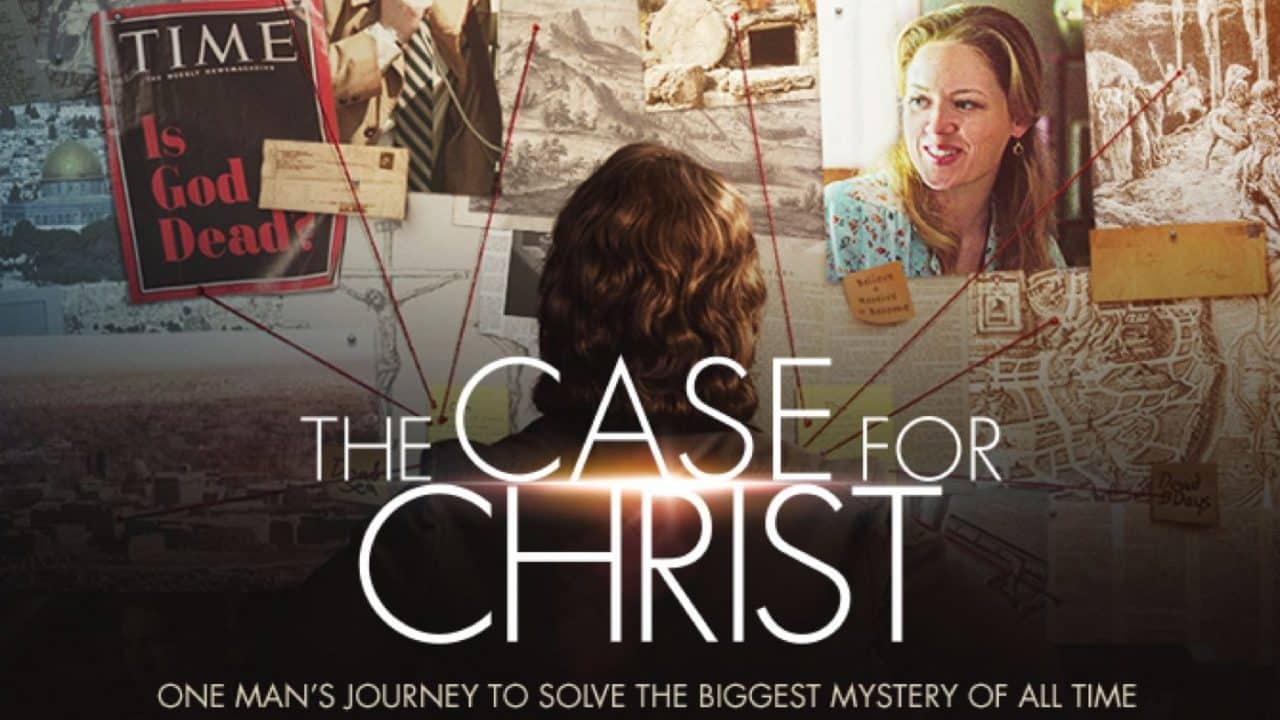

So, he did what any investigative journalist would do. He decided to debunk the whole thing. He used his legal training to go after the core of the Christian faith: the resurrection of Jesus. If he could prove that didn't happen, the whole house of cards would fall. That’s the origin story of The Case for Christ.

👉 See also: Converting 175 f to c: The Temperature Sweet Spot You're Probably Using Wrong

What Strobel Actually Found When He Went Digging

The book isn't just a memoir; it's a series of interviews. Strobel traveled across the country to grill experts—PhDs, historians, and world-class scholars. He wasn't looking for Sunday school answers. He wanted to know about the "biographical evidence." Is the New Testament actually reliable? Or is it just a game of telephone that got out of hand?

He sat down with Dr. Craig Blomberg, a heavy hitter in New Testament studies. They dug into the synoptic gospels. One of the biggest hurdles for skeptics is the gap between when Jesus lived and when the accounts were written. Usually, in ancient history, we’re lucky if we have a biography written within 500 years of the person’s life. With Jesus, we’re looking at decades. That might sound like a long time to us, but in the world of ancient historiography, it’s a blink of an eye.

Honestly, the "telephone game" argument—where the story changes every time someone tells it—doesn't really hold up when you look at how oral traditions worked in first-century Jewish culture. These people were pros at memorization. Rabbis had the entire Torah memorized. The idea that they’d just forget the core teachings or the "miracle" bits within a few years is kinda unlikely when you look at the cultural context.

The Science and the Scars

One of the more intense chapters involves Dr. Alexander Metherell. He’s a medical doctor who analyzed the physical toll of the crucifixion. This part of The Case for Christ gets pretty graphic. Strobel wanted to know if Jesus could have survived the cross—the so-called "Swoon Theory."

Metherell basically shuts that down. He describes hematidrosis (bloody sweat caused by extreme stress) and the effects of a Roman flagrum. We’re talking about leather thongs with lead balls and sharp bone woven in. It didn't just bruise; it tore muscle and exposed skeletal structure. By the time Jesus got to the cross, he was already in hypovolemic shock. The idea that he survived being nailed to a piece of wood, stayed in a cold tomb for three days without medical care, and then convinced everyone he had a "glorious resurrected body" is, medically speaking, a stretch.

It’s these kinds of technical details that make the book stick in your head. It moves away from "just have faith" and leans into "look at the trauma report."

The Empty Tomb and the "Crazy" Witnesses

Then there's the issue of the empty tomb. Skeptics have been trying to explain this one away for two thousand years. Did the disciples steal the body? Did they go to the wrong tomb?

👉 See also: The Vintage Secretary Writing Desk: Why These Weird, Fold-Down Antiques Are Making a Massive Comeback

Dr. William Lane Craig, a philosopher and theologian, walks Strobel through the "Criteria of Embarrassment." This is a fancy historical tool. Basically, if you’re making up a story to start a movement, you don't include details that make you look bad or weak.

In the first century, a woman’s testimony was basically worthless in a court of law. It's sad, but it's true for that time. Yet, all four gospels say that women were the first ones to find the empty tomb. If the disciples were inventing a lie to convince the world Jesus rose from the dead, they never would have made women the primary witnesses. They would have picked Peter or some high-ranking official. The fact that they kept the women in the story suggests they were stuck with a truth they couldn't change, even if it was socially "embarrassing" at the time.

Why Some People Still Aren't Buying It

We have to be fair here. The Case for Christ is written by someone who ended up becoming a believer. Critics often point out that Strobel didn't interview any "hostile" witnesses for the book. He didn't sit down with a staunch atheist scholar like Bart Ehrman to get a rebuttal in real-time.

- The scholars he interviewed are all biased toward Christianity.

- The book simplifies very complex textual criticisms.

- The "legal" framework is a bit of a literary device; it’s not a literal courtroom trial.

A lot of the pushback centers on the idea of "minimal facts." Skeptics argue that even if we agree the tomb was empty and people thought they saw Jesus, it doesn't automatically mean a supernatural resurrection occurred. There could be other naturalistic explanations we haven't figured out yet. Strobel’s argument is that the resurrection is the "best" explanation that fits all the pieces of the puzzle, but for many, the supernatural is a bridge too far no matter how much circumstantial evidence you pile up.

The Archaeological Paper Trail

Archaeology is usually where legends go to die. If the Bible was just a bunch of myths, you'd expect the geography and the politics to be all wrong. Strobel talked to Dr. John McRay about this.

Luke, who wrote the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts, used to be considered a bit of a hack by some 19th-century critics. They thought he made up titles for officials. But then, archaeology caught up. Inscriptions were found that used the exact specific, weird titles Luke used—titles like "politarchs" in Thessalonica. It turns out Luke was a first-rate historian.

Does a correct zip code prove the letter inside is true? Not necessarily. But it does show the author was actually there, or at least talking to people who were. It builds a level of trust. When you read The Case for Christ, you start to see that the New Testament isn't written like "Once upon a time" in a galaxy far, far away. It’s rooted in specific towns, under specific governors, during specific festivals.

The Fingerprint of God in Science?

Toward the end of the broader "Case" series (he later wrote The Case for a Creator), Strobel touches on the fine-tuning of the universe. This is a bit of a pivot from the historical Jesus, but it's relevant because it addresses the "why" behind the "what."

If the gravity of the universe were different by one part in $10^{60}$, we wouldn't be here. That’s a decimal point followed by 60 zeros. If the expansion rate of the universe was slightly off, everything would have collapsed back in on itself or flown apart too fast for stars to form. For a guy like Strobel, these aren't just "lucky breaks." They look like intent.

The Transformation That Can’t Be Quantified

The most compelling part of the book for many isn't the data—it's the change in Strobel himself. He started as a cynical, hard-drinking journalist who was pretty much a jerk to his family. By the end of his investigation, he was a different person.

This leads to the "Argument from Changed Lives." It's not a legal proof, but it's a powerful observation. The disciples were cowards when Jesus was arrested. Peter denied him three times just to save his own skin. Then, suddenly, they’re all willing to be tortured and executed for claiming they saw him alive.

People will die for a lie if they think it's the truth. But people don't usually die for a lie when they know they made it up. If the disciples stole the body, they knew it was a scam. Yet they went to their graves—stoned, crucified, beheaded—without ever recanting. That’s a huge psychological hurdle to clear if you're trying to prove the whole thing was a hoax.

Making Sense of it All Today

If you're looking at The Case for Christ today, you've gotta realize it’s a product of its time but the questions are evergreen. We live in a world of "fake news" and deepfakes. The idea of searching for objective truth is more relevant than ever.

Whether you walk away convinced or still skeptical, the book forces you to deal with the historical person of Jesus. You can't just dismiss him as a "nice moral teacher." As C.S. Lewis famously argued (and Strobel echoes), a guy who claims to be God isn't a "nice teacher." He’s either a lunatic, a liar, or exactly who he says he is.

Actionable Ways to Test the Evidence Yourself

Don't just take Strobel’s word for it—or mine. If you actually want to get to the bottom of this, you need to do a bit of your own legwork.

- Read the primary sources. Skip the devotionals for a second and just read the Gospel of Mark. It’s the shortest and likely the earliest. Look for those "embarrassing" details.

- Compare the creeds. Look at 1 Corinthians 15:3-7. Most historians—including the skeptical ones—agree this creed dates back to within two or three years of the crucifixion. It’s a snapshot of what the very first Christians believed.

- Check the "hostile" scholars. Read Bart Ehrman’s Did Jesus Exist? He’s an agnostic/atheist, but he spends the whole book debunking the idea that Jesus was a myth. It’s interesting to see where the "secular" and "sacred" historians actually agree (like the fact that Jesus was definitely crucified under Pontius Pilate).

- Look at the "Minimal Facts" approach. Gary Habermas has done extensive work on this. He only uses facts that virtually every scholar (liberal, conservative, or otherwise) agrees on. See if a resurrection is the only thing that explains those facts.

Strobel’s journey wasn't about a sudden bolt of lightning. It was a slow, agonizing grind through documents and data. It took him two years. If you’re honestly seeking, be prepared for it to take some time. Truth usually doesn't reveal itself in a thirty-second TikTok clip. It’s buried in the dirt of history, waiting for someone to pick up a shovel.