Honestly, most people read William Blake and think of "The Tyger" or some vague, flowery idea of 18th-century Romanticism. But if you really look at The Chimney Sweeper William Blake wrote—well, both versions he wrote—you aren't looking at a Hallmark card. You're looking at a crime scene.

Blake didn’t just write about kids. He wrote about "climbing boys," some as young as four or five, who were literally sold by their fathers into a life of soot and slow-motion suffocation. It's dark stuff. You’ve probably heard the lines about "weep! weep! weep!" in an English class once, but there’s a massive gap between the poem's surface and the gritty, horrifying reality of 1789 London.

The Brutal Reality Behind the Poem

London back then was a mess. After the Great Fire, building codes changed, making chimneys narrower and more winding to prevent future disasters. Great for the city, but a death sentence for children. These flues were sometimes only 9 inches wide. You couldn't fit a brush up there, so you used a human being.

These kids weren't just "sweepers." They were "climbing boys." They had to "buff it"—climb completely naked so their clothes wouldn't get snagged and trap them. They used their knees and elbows to shimmy up, scraping their skin raw until it developed thick, ugly calluses. To speed things up, some "masters" would literally light a fire under the kids' feet or poke them with pins. That’s where the phrase "light a fire under someone" actually comes from. It isn't a cute motivational idiom; it’s a memory of child abuse.

Blake wasn't making things up for dramatic effect. He lived in London. He saw these kids, covered in black dust, crying out " 'weep! 'weep!" because they were too young to even pronounce the word "sweep."

Why the Two Versions Matter

Blake published two poems with the exact same title. One is in Songs of Innocence (1789) and the other is in Songs of Experience (1794). If you only read one, you're missing the point.

The "Innocence" Version: A False Comfort

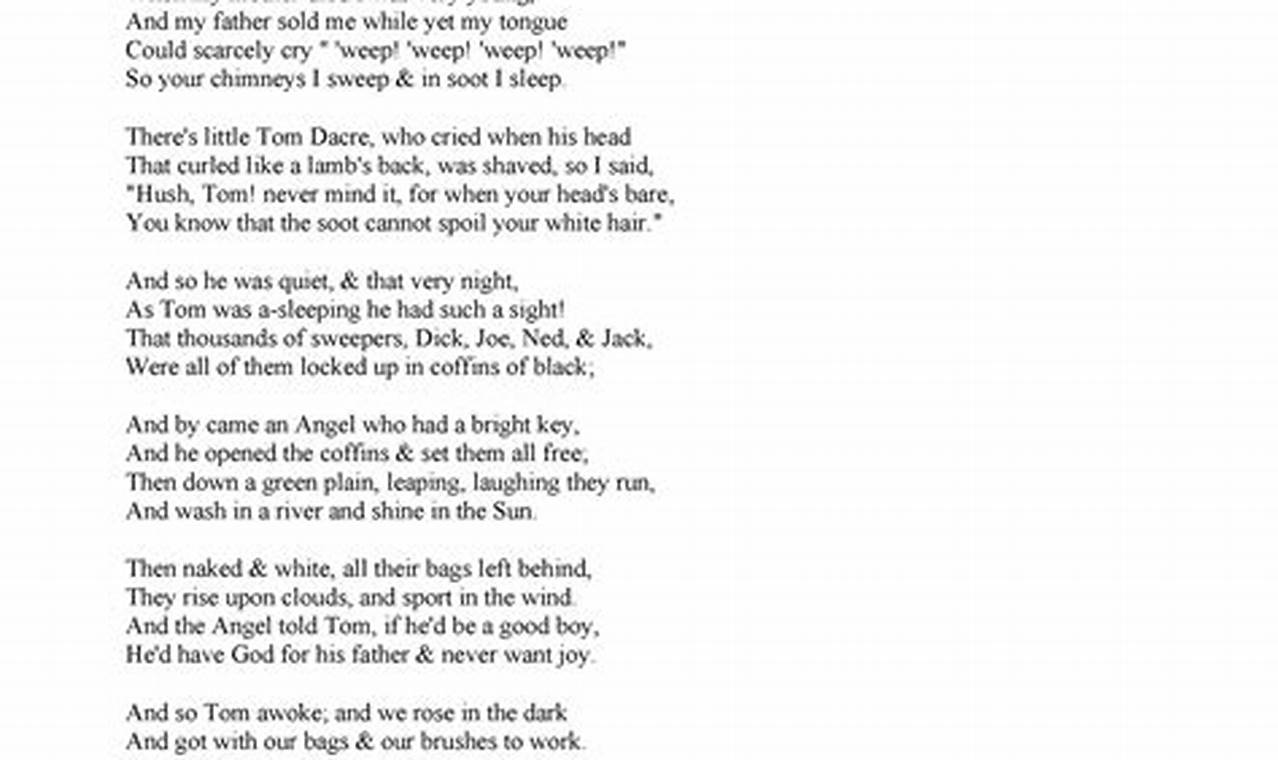

In the first poem, a boy named Tom Dacre has a dream. He sees thousands of sweepers locked in "coffins of black." An angel arrives with a bright key, opens the coffins, and sets them free to play in a green plain. It sounds lovely, right? Wrong.

👉 See also: The Sun Blessed Prince: Why This Niche Trope Is Dominating Modern Fantasy

The angel tells Tom that if he’s a "good boy," God will be his father and he'll never want for joy. The poem ends with: "So if all do their duty they need not fear harm."

This is Blake being incredibly sarcastic. He’s showing how the Church and society used the promise of a happy afterlife to keep these kids obedient while they were being worked to death. It’s a "shut up and work" manual disguised as a divine promise. The "coffins of black" aren't just metaphors; they are the chimneys the kids died in.

The "Experience" Version: The Angry Truth

Fast forward to 1794. The second version of The Chimney Sweeper William Blake gave us is much shorter and way more biting.

An adult narrator finds a "little black thing among the snow," crying. When asked where his parents are, the kid says they’ve gone to the church to pray. They "clothed me in the clothes of death" and "taught me to sing the notes of woe."

The kid is smart. He knows his parents and the King and the Priest are all in on it. They "make up a heaven of our misery." There's no angel here. No dream. Just a cold, snowy reality and a kid who knows he’s been sold out.

The Health Hazards Nobody Talks About

We talk about the "loss of innocence," but the physical loss was just as bad. These kids suffered from what was essentially the first recognized industrial cancer: Chimney Sweep Cancer (scrotal cancer caused by constant soot exposure).

- Deformed limbs: Their bones grew crooked from being cramped in flues.

- Blindness: Soot inflammation destroyed their eyes.

- Suffocation: Getting stuck in a bend was common. If a kid got stuck, the master might just leave him there and wait for him to die, then break the bricks to get the body out later.

Blake’s poetry was a protest. He was writing at a time when there were zero labor laws. The first "Act for the Better Regulation of Chimney Sweepers" wasn't passed until 1788, and it was barely enforced. It said kids had to be at least eight years old, but masters just lied about the age. It took until 1875—nearly a century after Blake's first poem—for the practice to finally be banned effectively.

What This Means for Us Today

It’s easy to look back and think, "Wow, the 18th century was barbaric." But Blake’s central question still hits home: who is benefiting from the suffering we choose not to see?

In his time, it was the wealthy Londoners who wanted warm, soot-free houses. Today, we might look at cobalt mines or fast-fashion factories. The "clothes of death" have just changed styles.

Blake’s genius wasn't just in the rhyming. It was in his ability to see the "mind-forged manacles" that make people accept cruelty as "duty." He wanted his readers to feel uncomfortable. He wanted them to see the kid in the snow.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Students

If you're studying Blake or just interested in the history of social reform, here is how you can actually apply this knowledge:

- Compare the Imagery: Look at the color palette Blake uses. In Innocence, it’s white hair vs. black soot. In Experience, it’s a black child vs. white snow. This isn't accidental; he's highlighting the total isolation of the child from the natural world.

- Trace the Reform: Research the "Climbing Boys' Act" and the work of Jonas Hanway. Seeing the legislative struggle helps you realize that Blake wasn't shouting into a void; he was part of a very real, very dangerous political movement.

- Analyze the "Father" Figure: In both poems, the biological father is either gone or the one who sold the child. Blake is critiquing the patriarchal structure of the era—where a father, a King, and a God are all figures of authority who fail to protect the most vulnerable.

- Look for Modern Parallels: Identify "invisible" labor in today’s economy. Blake’s work is a template for how to use art to expose systemic issues that the "pious" would rather ignore.