If you look at a civil war mason dixon line map, you’re actually looking at a mistake. Well, maybe not a mistake, but a massive misunderstanding that’s been baked into American culture for over 150 years. Most people think of that line as the definitive split between the North and the South during the 1860s. It’s the "line in the sand."

But honestly? It was never meant to be that.

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon weren't thinking about slavery or secession when they were trudging through the wilderness in the 1760s. They were surveyors hired to settle a petty, violent property dispute between the Penns of Pennsylvania and the Calvert family of Maryland. They were drawing a boundary for taxes and land deeds, not a geopolitical wall. Yet, by the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, that line had become the psychological and physical edge of a fractured nation.

The Map That Defined the "Border States"

When you pull up a civil war mason dixon line map, the first thing you notice is the messy reality of the "Middle." History books like to paint the war in blue and grey. Crisp. Clean. But the map tells a different story.

The Mason-Dixon line technically ends at the western border of Pennsylvania. It doesn't even touch the Ohio River, though we often pretend it does. During the war, this created a bizarre "gray zone." Take Maryland, for example. Geographically, it’s south of the line. Culturally and economically, it was tied to the South. But it stayed in the Union—mostly because Abraham Lincoln couldn't afford to have the U.S. capital surrounded by Confederate territory. He suspended habeas corpus and sent in troops to make sure that map stayed blue.

Then you've got Delaware. It’s east of the line, technically "South" of the Pennsylvania border, but it never seceded.

The line was a ghost. It haunted the politics of the era. By 1860, the Mason-Dixon line had morphed from a property marker into the "Sectional Line." It was the threshold of freedom for thousands of enslaved people following the North Star. If you crossed that line, the laws changed. The air felt different. But even that is a simplification. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 meant that crossing the line on a map didn't actually guarantee safety.

Why the Map Looks So Weird Around West Virginia

One of the most fascinating parts of any civil war mason dixon line map is the jagged birth of West Virginia. Before 1863, Virginia was one big state. But the people living in the rugged Appalachian mountains didn't have much in common with the plantation owners in the Tidewater region.

They didn't own many slaves. They didn't want to fight for the Confederacy.

So, they basically seceded from the secession. This created a massive indentation in what we think of as the "Southern" border. Suddenly, the North had this huge wedge of territory driving down into the heart of the South. If you’re looking at a map from 1861 versus 1864, the line shifts dramatically. It’s a reminder that borders aren't permanent. They are made of blood and political willpower.

💡 You might also like: The portable air conditioner 8000 BTU reality check: What you actually need to know before buying

The Surveying Feat Nobody Talks About

We should probably give some credit to Mason and Dixon themselves. These guys weren't just guys with measuring tapes. They were using high-end astronomical equipment. They used the stars to determine latitude with incredible precision.

They hauled a heavy zenith sector through dense forests and over mountains.

They marked the line with limestone "crownstones" brought over from England. Every five miles, a stone featured the coat of arms for Penn on one side and Calvert on the other. During the Civil War, these stones were still there, sitting quietly in the woods while soldiers marched past them. Some of those stones are still there today, though many are chipped or buried in suburban backyards.

The Cultural Weight of the Line

Why do we still care about this map? Because it created the concept of "Dixie."

The name "Dixie" is often argued to have come from the "Dixon" in Mason-Dixon. It’s the root of a specific identity. Even today, if you drive across the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, you see it. You see the signs. You see the subtle shift in accents. You see the flags.

The civil war mason dixon line map became a shorthand for "us versus them."

But the reality was always more fluid. In places like Cairo, Illinois, or Southern Indiana, the "Northern" population was deeply sympathetic to the South. Meanwhile, in the mountains of Tennessee, "Southern" Unionists were fighting a guerrilla war against the Confederacy. The map shows a line, but the ground showed a gradient.

Misconceptions About the Ohio River

You’ll often hear people say the Mason-Dixon line follows the Ohio River. It doesn't.

The Ohio River became the de facto extension of the line under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which banned slavery in the new territories. This effectively stretched the "free/slave" boundary all the way to the Mississippi River. When you look at a comprehensive civil war mason dixon line map, you usually see the actual surveyed line (the PA/MD border) and then a dotted or highlighted line following the river.

It's a "mental map" more than a legal one.

How to Read an Original 1860s Map

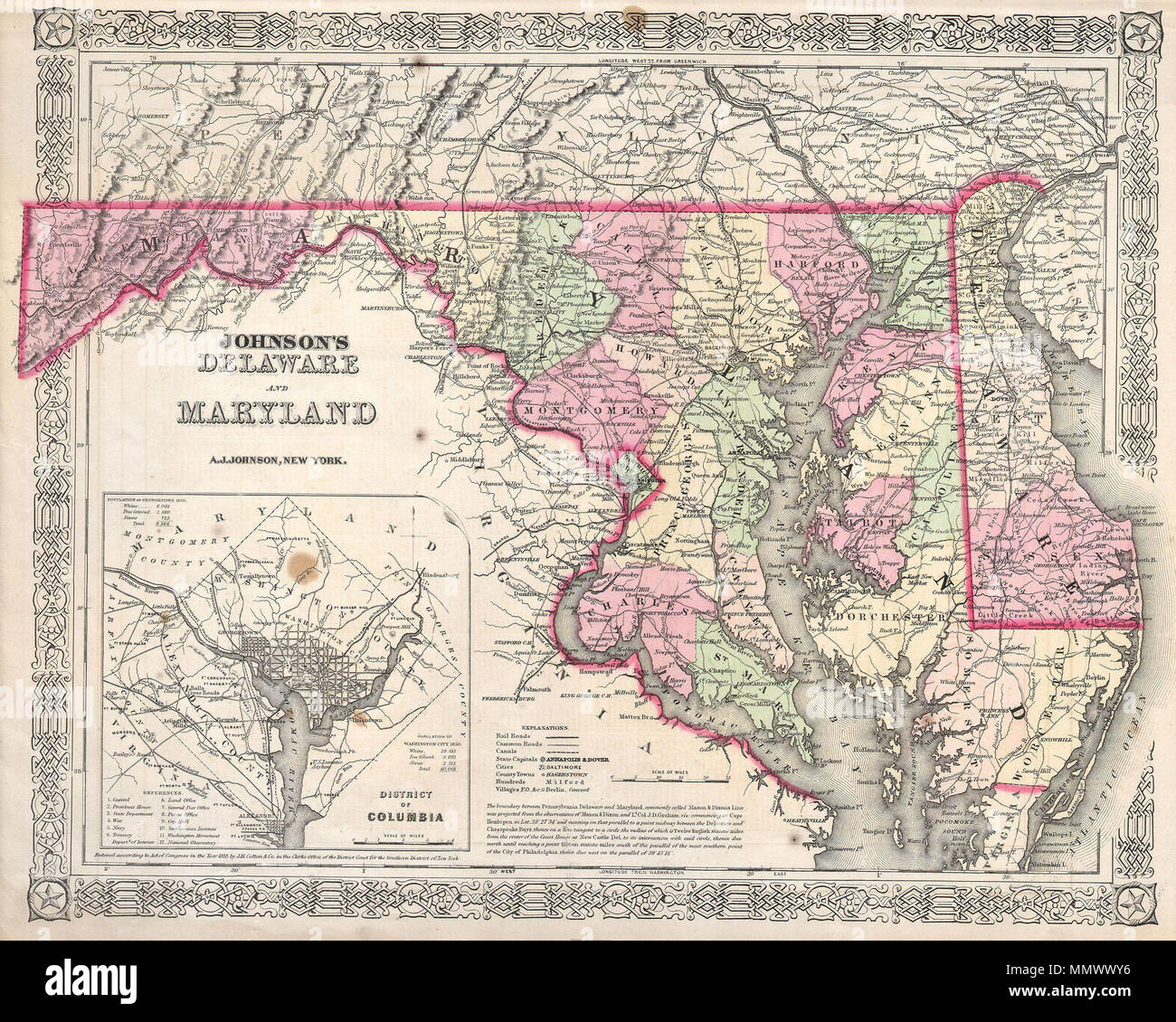

If you’re a collector or a history buff trying to find an authentic map from the era, you need to look at the publishers. Names like Colton, Johnson, and Mitchell were the kings of cartography back then.

- Look for the "Slave States" Shading: Many maps from 1861 used specific colors or hatching to indicate where slavery was legal.

- Check the Railroads: The Mason-Dixon line isn't just about politics; it’s about infrastructure. The North had a vastly more complex rail network crossing that line than the South did.

- Identify the Territories: In 1861, the West was still a mess of unorganized territories. How a map handles Kansas or Nebraska tells you a lot about its political leanings.

- The "Neutral" States: Some maps produced early in the war show Kentucky and Missouri in a different color, reflecting their initial attempt to stay out of the fight.

The Line Today: More Than Just History

You can actually visit the line. You can hike the Mason-Dixon Trail. But as you walk it, you realize how arbitrary it feels. It cuts through farm fields. It bisects roads. It doesn't follow a ridge or a river. It’s a straight line drawn by men who were looking at the stars, trying to solve a land dispute that had nothing to do with the war that would eventually make their names famous.

The civil war mason dixon line map is a lesson in unintended consequences. A survey meant to stop farmers from shooting each other over cow pastures became the boundary for a conflict that nearly destroyed the United States.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Map

If you want to dive deeper into the geography of the conflict, don't just look at a static image on Google.

- Use the Library of Congress Digital Collection: They have high-resolution scans of original Civil War era maps where you can see the individual farms and crossroads.

- Visit a "Cornerstone": If you’re in the Mid-Atlantic, find one of the original 1760s markers. It puts the scale of the "line" into perspective.

- Overlay Modern Geography: Use tools like Google Earth to overlay a 1860 map over modern topography. It’s wild to see how many modern highways follow the exact troop movements that were dictated by the Mason-Dixon boundary.

- Read the Journals: Charles Mason’s daily journals are public record. They don't talk about the Civil War, obviously, but they show the grueling physical labor required to create the map that would later define American identity.

The line wasn't just a border. It was a scar. And like most scars, it tells a story about a wound that took a very long time to heal. Even now, the map reminds us that where we draw the line matters less than why we drew it in the first place.

Next Steps for Research:

Check the "Civil War Sites Advisory Commission" maps for specific battlefield locations that sit directly on or near the boundary. Specifically, look at the geography of the "Pennsylvania Invasion" of 1863; it shows how the Mason-Dixon line acted as a psychological barrier for Robert E. Lee’s troops as they moved into "enemy" soil for the first time. For a deeper look at the surveying itself, the book Drawing the Line by Edwin Danson offers the best technical breakdown of how Mason and Dixon actually pulled off this feat without modern GPS.