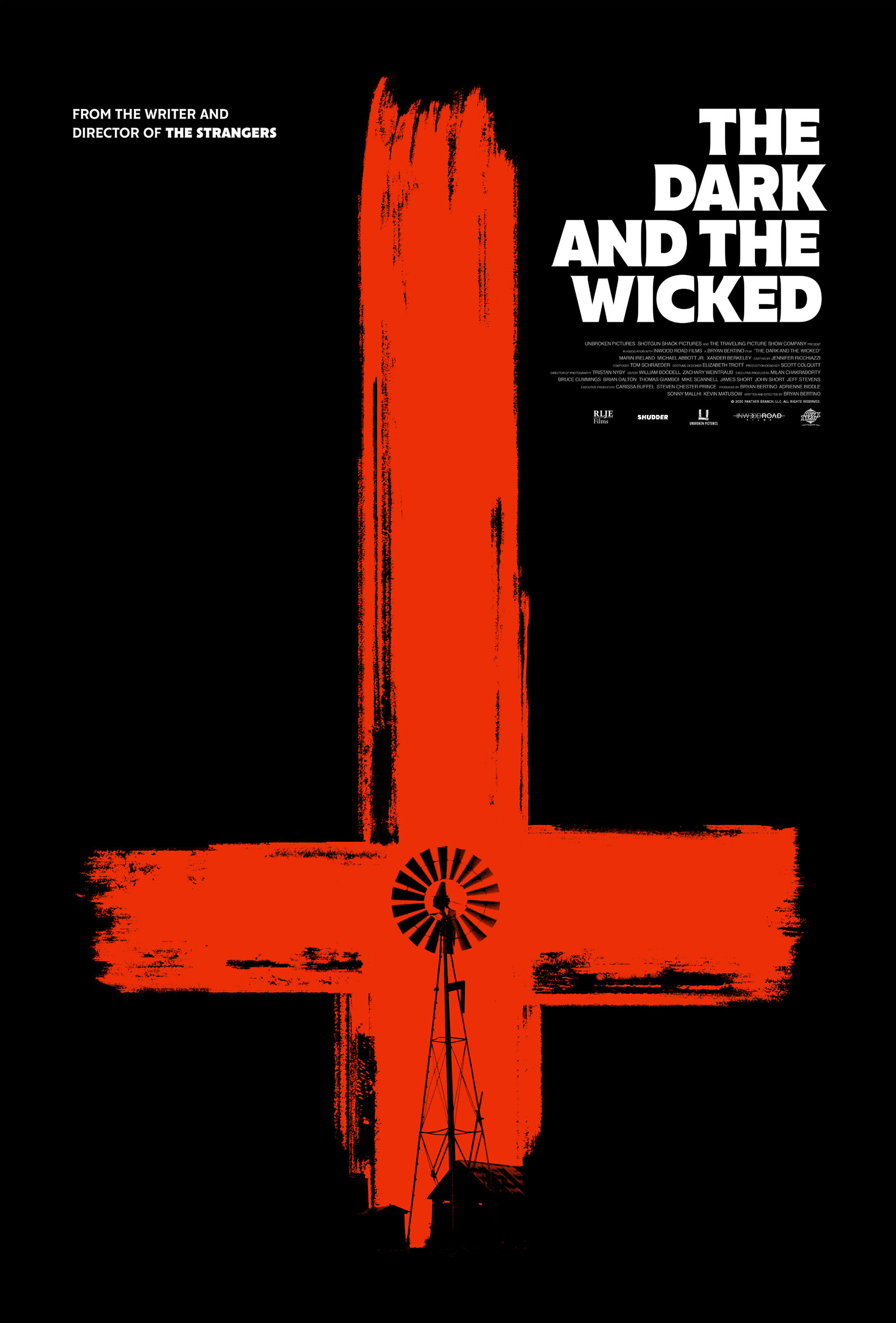

Bryan Bertino is a master of making you feel unsafe in your own house. You probably remember The Strangers. It was that 2008 flick where a couple gets terrorized just because they were home. It was lean, mean, and totally devoid of hope. Well, The Dark and the Wicked takes that same bleak energy and turns the volume up until the speakers blow out. Honestly, it’s one of the most oppressive horror movies released in the last decade. It doesn't care about your feelings. It doesn't care about a "happily ever after."

It’s a movie about grief, sure. But it’s also about something much nastier.

The story follows two siblings, Louise and Michael, who return to their family farm to watch their father die. He’s bedridden, gasping for air, basically a shell. Their mother is losing her mind—or so it seems. But as the nights crawl by, it becomes clear that whatever is haunting that farmhouse isn't just a byproduct of sadness. There’s a presence. Something ancient. Something that wants more than just a soul.

Why The Dark and the Wicked Feels So Different

Most horror movies follow a set of rules. You know the drill. There’s a priest, or a medium, or a clever protagonist who finds a dusty book in the attic that explains exactly how to banish the demon. You say the Latin words, you splash some holy water, and the sun comes up.

The Dark and the Wicked throws those rules into a woodchipper.

There is no "why" here. When the siblings encounter a local priest—played with a chilling, stuttering intensity by Xander Berkeley—he doesn't offer comfort. He offers a warning that sounds more like a death sentence. He suggests that the devil doesn't need an invitation. He doesn't need you to play with an Ouija board or move into a house built on an ancient burial ground. He just shows up because he can. That’s terrifying. It taps into a primal fear that bad things happen to good people for no reason at all.

Marin Ireland and Michael Abbott Jr. carry the weight of the film. Their performances are stripped raw. You can see the exhaustion in their eyes. Most horror actors spend the movie screaming, but these two spend it vibrating with a quiet, low-level dread that feels way more authentic.

🔗 Read more: Major Lazer Run Up: Why This 2017 Collab Still Hits Different

The Visual Language of Dread

Bertino and his cinematographer, Tristan Nyby, use the Texas landscape like a character. It’s wide, flat, and impossibly lonely. During the day, the sun is harsh and unforgiving. At night, the darkness is a physical weight. They use long takes where your eyes frantically scan the background for movement. Usually, there’s nothing. But then, there’s something.

One scene involving a kitchen knife and some carrots is particularly legendary among horror fans. It’s slow. It’s rhythmic. You know exactly what’s going to happen, yet when it does, it’s still a gut punch. It’s the kind of "human-level" horror that sticks with you longer than any CGI monster ever could.

Understanding the "Wicked" Element

We need to talk about the ending. Or rather, the lack of a traditional resolution.

A lot of people walked away from The Dark and the Wicked feeling frustrated. They wanted answers. They wanted to know if the father was "possessed" or if the mother was just suffering from a psychotic break. But the movie argues that it doesn't matter. Whether it’s a literal demon or the metaphorical demon of terminal illness, the result is the same: loss.

The film suggests that evil is opportunistic. It waits for the cracks in the human psyche—the moments of deepest mourning—and it pries them open.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Good Advice Matters More Than the Movie Itself

Realism vs. Supernatural

What makes the film work is how it grounds the supernatural in the mundane. You’ve got goats crying in the middle of the night. You’ve got the sound of a rocking chair. You’ve got the clinking of knitting needles. These are sounds of a farm, but in the context of the film, they become serrated.

Bertino has gone on record saying he wanted to explore the idea of "believing" versus "knowing." The siblings don't want to believe in the supernatural. They are practical people. But as the evidence mounts, their logic fails them. That’s a recurring theme in Bertino’s work. In The Strangers, the killers' motivation was simply "because you were home." In The Dark and the Wicked, the motivation is even more nihilistic. The "wicked" thing is there because the "dark" provided an opening.

Common Misconceptions About the Movie

A lot of critics labeled this "Elevated Horror." Honestly, that’s a bit of a lazy term. It implies that "regular" horror is somehow lesser. This movie isn't trying to be "elevated"; it’s trying to be visceral. It’s a folk-horror tale stripped of the folklore. There are no complicated rituals or secret cults in the woods. It’s just a family falling apart under the pressure of an unseen force.

- Is it a jump-scare movie? Not really. There are a few, and they’re effective, but the movie relies on atmospheric dread. It’s a "slow burn" in the truest sense.

- Is there a hidden meaning? Many viewers see the demon as a metaphor for the way dementia or terminal illness "steals" a person before they actually die. The "wicked" presence is the hollowed-out version of the person you love.

- Is it related to The Strangers? Only spiritually. It’s the same director exploring similar themes of isolation and helplessness.

The sound design is arguably the scariest part of the whole experience. If you watch this with headphones, be prepared. Every creak of the floorboards sounds like a bone snapping. The whispers aren't just background noise; they feel like they’re happening right behind your head. It’s an assault on the senses.

Critical Reception and Legacy

When it hit the festival circuit and later streaming services, it became a word-of-mouth hit. It holds a high rating on Rotten Tomatoes (around 91%) because it doesn't flinch. It’s a rare horror movie that feels like it has a soul, even if that soul is being devoured.

Critics like Brian Tallerico from RogerEbert.com pointed out that the film works because it feels so personal. It doesn't feel like a studio-mandated product. It feels like a nightmare someone actually had and then spent millions of dollars to recreate for us.

How to Approach a Rewatch

If you’re going back to watch The Dark and the Wicked, or if it’s your first time, you need to set the mood. This isn't a "popcorn and friends" movie. This is a "lights off, phone away, sit in the dark" movie.

- Watch the shadows. Bertino loves hiding things in the corners of the frame.

- Pay attention to the mother's journals. They provide the only real "context" for what started happening before the siblings arrived.

- Listen to the silence. The moments where there is no music are often the most telling.

The film is a reminder that horror can be more than just monsters under the bed. It can be the silence of a house where someone is dying. It can be the realization that you can't protect the people you love.

💡 You might also like: Waist Deep: What Most People Get Wrong About the Meagan Good and Tyrese Movie

Actionable Insights for Horror Fans

If you loved the bleakness of this film, there are a few things you can do to dive deeper into this specific sub-genre of nihilistic horror.

First, check out the rest of Bryan Bertino’s filmography. The Monster (2016) is another great example of him using a horror creature to explore a damaged relationship—this time between a mother and daughter. It’s less "scary" than The Dark and the Wicked, but it’s just as heavy.

Second, look into "New Tenancy" horror. This is a niche where the horror is tied to the location and the inevitability of fate. Movies like Relic (2020) or Saint Maud (2019) pair well with this one. They all deal with the intersection of mental health, aging, and the possible presence of the divine or the devilish.

Lastly, don't look for a "solution" to the movie. The power of The Dark and the Wicked lies in its ambiguity. The moment you explain a ghost, it stops being scary. By refusing to explain the "wicked," Bertino ensures that the fear lingers long after the credits roll.

The next time you’re alone in a quiet house and you hear a floorboard creak, you’ll think of this movie. You’ll wonder if it’s just the house settling, or if the "dark" has finally found a way in. That’s the mark of a truly great horror film. It changes the way you perceive your own surroundings. It makes the familiar feel dangerous. And honestly? That's exactly why we watch these things in the first place.