Frederick Douglass didn’t just walk away. He didn't just run into the woods and hope for the best. Honestly, when you look at the logistics of the escape from slavery Frederick Douglass executed in 1838, it feels more like a high-stakes spy thriller than a dry history lesson.

He was twenty years old. He was technically "hired out" as a ship caulker in Baltimore, which gave him a tiny bit of geographic wiggle room, but he was still property in the eyes of the law. One wrong look or a nervous stutter at a ticket counter would have meant being sold "down river" to the cotton fields of the Deep South. That was basically a death sentence.

The Sailor Suit and the Fake Papers

Most people think Douglass just followed the North Star. He did, eventually, but the actual breakout relied on a very specific, very risky disguise. He dressed as a sailor.

Why a sailor? Because in the 1830s, "Black jacks"—free Black seamen—were everywhere in mid-Atlantic ports. They had a certain "swag," for lack of a better word, that commanded a sliver of respect. They were also mobile.

Douglass borrowed a "protection" paper from a friend. This was a document that proved the bearer was a free American sailor. Here's the catch: the description on the paper didn't look a thing like him. If the conductor on the train out of Baltimore had actually read the physical description, Douglass would have been finished.

He boarded a train headed for Wilmington, Delaware. His heart was hammering. He later wrote about how he could feel it thumping against his ribs, certain that everyone could hear his terror. But he played the part. He talked the talk of the sea. When the conductor came by, Douglass didn't hand over a pass from a master; he flashed the sailor’s protection. The conductor glanced at the eagle stamped on the top and kept moving.

Luck? Maybe. But it was also a calculated play on the social biases of the time.

The Close Calls You Didn't Learn in School

It wasn't a straight shot. To complete the escape from slavery Frederick Douglass had to navigate a gauntlet of coincidences that nearly ruined everything.

While sitting on the train, he looked out the window and saw a man he knew—a shipbuilder he had worked for in Baltimore. The man was looking right at him. For whatever reason—perhaps the disguise was that good, or perhaps the man just couldn't process what he was seeing—the shipbuilder didn't raise the alarm.

Then there was the ferry. He had to cross the Susquehanna River. On the boat, he encountered another person who recognized him. It's wild to think about. Every few miles, the entire future of the American abolitionist movement rested on a stranger's choice to mind their own business.

🔗 Read more: Childrens Christmas Joke Ideas That Actually Make Your Kids Laugh

Why the Escape from Slavery Frederick Douglass Managed Still Matters

We talk about the Underground Railroad like it was a literal train. It wasn't. For Douglass, it was a series of frantic transitions.

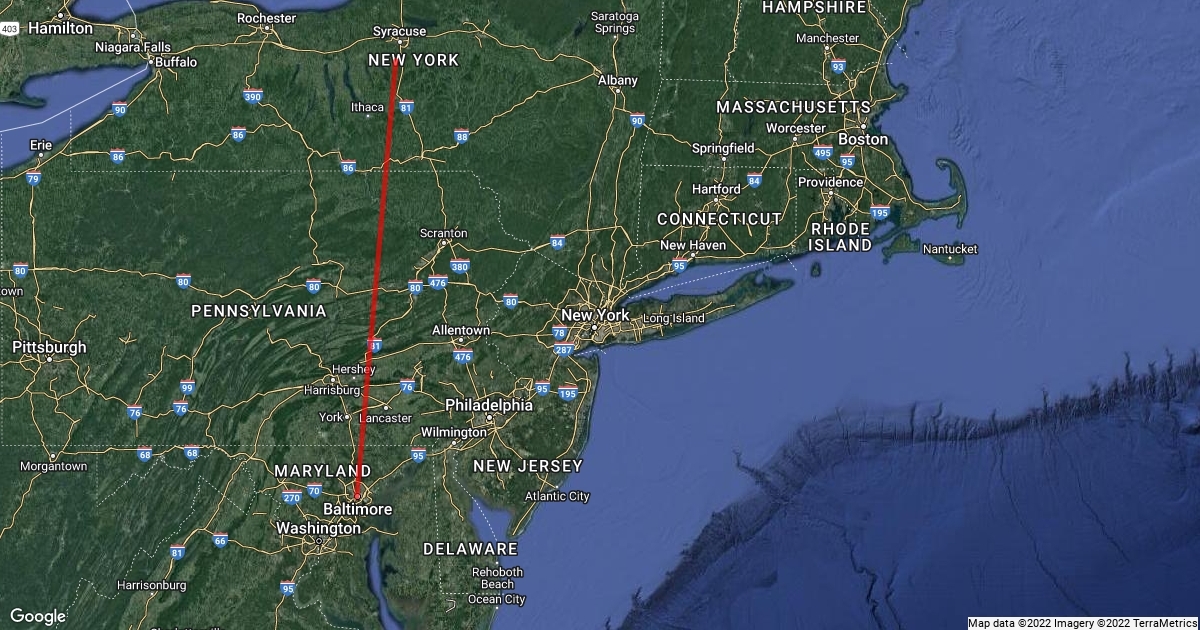

- Train from Baltimore to Wilmington.

- Steamboat to Philadelphia.

- Another train to New York City.

He arrived in New York in less than twenty-four hours. Imagine that. One day you are a piece of legal property in Maryland, and the next you are standing on a street corner in Manhattan.

But he wasn't safe. New York was crawling with slave catchers. He was a "fugitive," a word that essentially gave any white person the right to kidnap him for a bounty. He was homeless, penniless, and couldn't trust a soul. He eventually met David Ruggles, a key operative in the New York Committee of Vigilance, who took him in and helped him get to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

The Mental Toll of the Run

Douglass later admitted that the physical escape was the easy part. The mental transition was the real mountain.

✨ Don't miss: Why Wish You Were Here Coffee Is Actually Worth the Hype

He had to rename himself. Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, he became Frederick Johnson, then finally Frederick Douglass—taking the name from a character in Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake. He had to shed an entire identity.

He also dealt with what we’d call survivor's guilt. He had left his friends behind. He had left the woman he loved, Anna Murray, though she joined him in New York shortly after and they were married. Anna is the unsung hero here; she sold her bed to help fund his escape. Without her savings and her support, he might never have made it off the docks.

The Logistics of Freedom

If you're trying to understand the escape from slavery Frederick Douglass pulled off, you have to look at the numbers.

He escaped on September 3, 1838. He was one of roughly 1,000 enslaved people who successfully fled to the North every year during that decade. That sounds like a lot, but when you realize there were nearly 2.5 million people enslaved in the U.S. at the time, you realize how narrow the needle's eye really was.

Douglass succeeded because he was literate. He had taught himself to read and write against the law, often by tricking white children into "contests" to see who could write letters better. This literacy was his real ticket. It allowed him to forge the mind of a free man before his body ever left Maryland.

Actionable Steps to Learn More

History isn't just about dates; it's about the mechanics of how people changed the world. If you want to dive deeper into the reality of Douglass's journey, here is how to get the real story:

- Read the 1845 Narrative. Start with Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It’s short, punchy, and he wrote it himself. Avoid the sanitized versions; read his actual words about the "blood-stained gate" of slavery.

- Visit the National Park Service sites. The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (Cedar Hill) in D.C. is great, but also look into the Underground Railroad hubs in New Bedford, Massachusetts. You can see the actual docks where he worked as a free man.

- Trace the route. Use digital mapping tools like those provided by the Maryland State Archives to see exactly where the Baltimore shipyards sat in relation to the train depots. Seeing the geography makes the risk feel much more "real."

- Support modern abolition. Slavery hasn't vanished; it’s changed form. Look into organizations like Free the Slaves or the International Justice Mission to see how the spirit of Douglass’s struggle continues in the fight against human trafficking today.

Frederick Douglass didn't just escape for himself. He spent the next fifty years making sure the door stayed open for everyone else. His journey from a Maryland shipyard to the halls of power in Washington D.C. started with a borrowed sailor's hat and the sheer, terrifying guts to get on a train.

That single day in September changed American history forever. It wasn't just a trip; it was a transformation.