You know the one. You’ve seen it on t-shirts, coffee mugs, and probably in the back of your middle school biology textbook. It’s a line of hairy apes slowly standing up straighter and straighter until—poof—there’s a tall, naked dude at the end holding a spear. It’s called the evolution of man chart, or more formally, the "March of Progress."

It’s iconic. It’s simple. Honestly, it's also a bit of a mess.

💡 You might also like: Is Today Jewish New Year? Why the Answer Changes Every Single Year

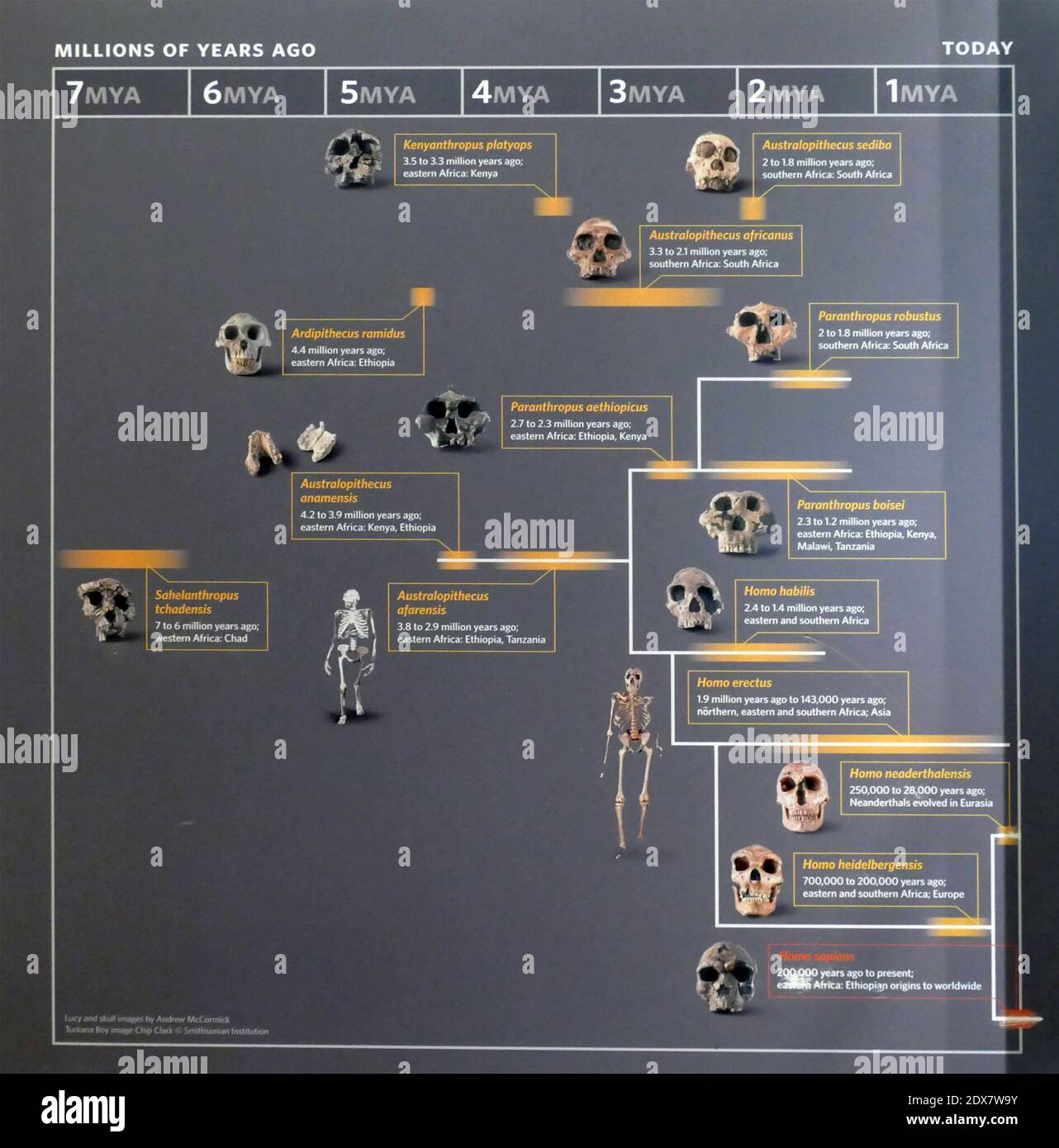

While that image did more to explain the concept of human history to the general public than almost any other piece of art, it accidentally taught us a version of history that doesn't really exist. Evolution isn't a ladder. It’s not a straight line where one species gets "better" and "upgrades" into the next one like a software update. It’s a messy, tangled bush. If you actually look at the fossil record, we weren't just marching toward "perfection." We were surviving, often alongside other types of humans who looked almost exactly like us.

Where the evolution of man chart actually came from

In 1965, Time-Life Books published a volume called Early Man. The illustrator, Rudolph Zallinger, created a fold-out spread that showed 15 different primate species in a row. It was meant to show a timeline, not a direct lineage. But because it looked so cool and was so easy to understand, the "March of Progress" became the definitive visual for how we became us.

The problem? Even the guy who wrote the text for that book, F. Clark Howell, knew it was an oversimplification. He basically warned that putting them in a line didn't mean one turned into the next. But humans love a good story. We love the idea of a steady climb from the "primitive" to the "advanced."

Scientific reality is a lot more chaotic. For most of our history, there were multiple species of "humans" walking around at the same time. Imagine a world where Homo sapiens shared the forest with Homo floresiensis (the "hobbits") or the Denisovans. That was the reality for the vast majority of our timeline. The evolution of man chart makes it look like a relay race where one runner passes the baton and then disappears. In reality, it was more like a crowded party where some people left early and others stayed to mingle.

The heavy hitters in our family tree

When you look at a modern evolution of man chart, you usually see a few specific characters.

First, there’s Australopithecus afarensis. Think of Lucy. She lived about 3 million years ago. She was short, had a brain about the size of a chimpanzee’s, but she could walk on two legs. This was a massive deal. Walking upright wasn't about being "better"—it was about surviving in changing environments where trees were getting further apart.

Then comes Homo erectus. These folks were the real world travelers. They were the first to really leave Africa and spread out into Europe and Asia. They used fire. They made complex tools. They stayed around for nearly 2 million years! To put that in perspective, we’ve only been here for about 300,000 years. Honestly, compared to them, we’re the new kids on the block who haven't proven we can last yet.

Neanderthals weren't just "dumb" versions of us

One of the biggest victims of the evolution of man chart is the Neanderthal. In the classic drawings, they’re often shown as slouching, brutish versions of Homo sapiens.

Total myth.

Neanderthals had brains as big as ours—sometimes bigger. They buried their dead. They made jewelry. They cared for the sick. We didn't "evolve" from them; we were cousins. We shared a common ancestor and lived at the same time. We even interbred. If you have European or Asian ancestry, you likely have about 1% to 4% Neanderthal DNA in your system right now. They didn't just disappear; they kind of folded into us.

The "missing link" is a bit of a fairy tale

People always ask about the "missing link." It’s a term that gets thrown around in news headlines every time someone finds a new bone in a cave. But biologists generally hate that phrase. It implies there is one specific skeleton that connects an ape to a human.

Evolution doesn't work in big jumps. It happens in tiny, microscopic shifts over millions of years. Every fossil is a link.

Take Ardipithecus ramidus, or "Ardi." Ardi lived about 4.4 million years ago. She had a big toe that could grasp branches, but her pelvis suggests she could also walk upright. She’s a "link," but she’s also her own unique creature that was perfectly adapted to her specific world. The evolution of man chart tries to force these creatures into a narrative of "becoming human," but they weren't trying to become anything. They were just trying to find lunch.

Why the chart still matters (despite being wrong)

If it’s so inaccurate, why do we still use it?

Because it’s a powerful metaphor. It captures the incredible journey of how a small, vulnerable primate became the dominant force on the planet. It shows the transition from being a part of nature to trying to control it.

However, when we look at the evolution of man chart today, we need to view it with a bit of skepticism. We need to remember the species that aren't on it. The "dead ends" that were actually successful for millions of years. The branches that broke off.

It also reminds us that we are still evolving. We aren't the "final product" at the end of the line. Evolution didn't stop once we started wearing pants and using iPhones. Our jaws are getting smaller because we eat soft food. Our immune systems are constantly recalibrating to new environments. We are still a work in progress.

What you can do to understand our history better

If you want to actually see the "bush" instead of the "line," there are better ways to spend your time than staring at a 60-year-old drawing.

- Check out the Smithsonian’s Human Origins project. They have an interactive family tree that shows how many different species overlapped. It’s mind-blowing to see how crowded the world was 100,000 years ago.

- Read "Sapiens" by Yuval Noah Harari. While some scientists argue over his interpretations, he does a great job of explaining how we weren't the only humans around and how we eventually "won" (or outlasted) the others.

- Look into the Denisovans. This is a relatively recent discovery. We found a finger bone in a cave in Siberia and realized it belonged to a whole group of humans we never knew existed. It proves there is still so much we don't know.

- Visit a local natural history museum. Seeing the actual scale of a Homo erectus skull versus a Homo habilis skull changes your perspective. It’s not just about height; it’s about the massive shift in brain capacity and jaw structure.

The evolution of man chart is a great piece of art, but it's a terrible map. To really understand where we came from, you have to embrace the mess. You have to accept that we aren't the pinnacle of a straight line, but rather the last surviving branch on a very old, very complex tree.

Next time you see that chart, just remember: the real story is way more interesting than a straight line. It's full of mystery, inter-species hookups, and long-lost cousins that we're only just beginning to rediscover.

Actionable Insight: To see the modern version of human history, search for "Hominin Phylogenetic Tree." This will show you the "bush" model that scientists actually use today. Understanding that we are just one branch of many helps put our current impact on the planet—and our vulnerability—into much sharper focus.