You know that feeling when a song just sticks in your craw because it feels a little too honest? That's the vibe with the first cut is the deepest lyrics. It’s a song that shouldn't have worked, written by a teenager who was still trying to find his feet in a London music scene that was obsessed with the "Summer of Love." But while everyone else was singing about flowers in their hair, Yusuf / Cat Stevens was writing about the brutal, scarring nature of a first breakup.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle the song exists in the form we know.

When Stevens wrote it in 1967, he wasn't the folk-rock superstar of Teaser and the Firecat yet. He was a 19-year-old kid named Steven Georgiou, and he was struggling. He actually sold the song for £30 to P.P. Arnold because he didn't think his own version was the "hit" version. Imagine that. You write one of the most enduring soul-searching anthems in history and hand it off for the price of a decent dinner and a few drinks because you're worried your voice sounds too rough.

The Raw Truth Inside the First Cut Is the Deepest Lyrics

The song doesn't play around. Right from the jump, it hits you with a heavy realization: "I would have given you all of my heart / But there's someone who's torn it apart."

It’s cynical. It's essentially a song about being "damaged goods" before you’ve even reached adulthood. Most love songs are about the current flame, but the first cut is the deepest lyrics are actually about the previous person. It’s a warning to a new lover. It’s saying, "Look, I want to love you, but I’m already broken." That kind of honesty was rare in the mid-sixties pop charts.

Most people think it’s just a catchy hook. It isn't.

If you look at the line "I still want you by my side / Just to help me dry the tears that I’ve cried," it reveals a selfish kind of grief. The narrator isn't necessarily in love with the new person; they’re using them as a bandage. It's dark. It's messy. It’s human.

💡 You might also like: Why The Perks of Being a Wallflower Actors Still Define a Generation

Why Sheryl Crow and Rod Stewart Both Claim It

It’s rare for a song to be a massive hit for three different people in three different decades. P.P. Arnold made it a soul classic in '67. Rod Stewart turned it into a raspy, 1970s stadium anthem. Then Sheryl Crow came along in 2003 and made it the definitive country-rock breakup track for a whole new generation.

Why does it keep working?

Because the central metaphor is perfect. Everyone remembers their first real heartbreak. That first time your chest actually physically ached because someone didn't want you anymore. Stevens captured that specific trauma. He argued that every subsequent relationship is just an echo of that first wound.

Rod Stewart’s version added a layer of "lad-rock" vulnerability. When he sings it, you hear the whiskey and the years of regret. But Sheryl Crow? She brought a weary, feminine strength to it. In her version, the lyrics feel less like a complaint and more like a factual observation of her own resilience. She’s acknowledging the scar but she’s still standing.

The Technical Brilliance of Stevens' Songwriting

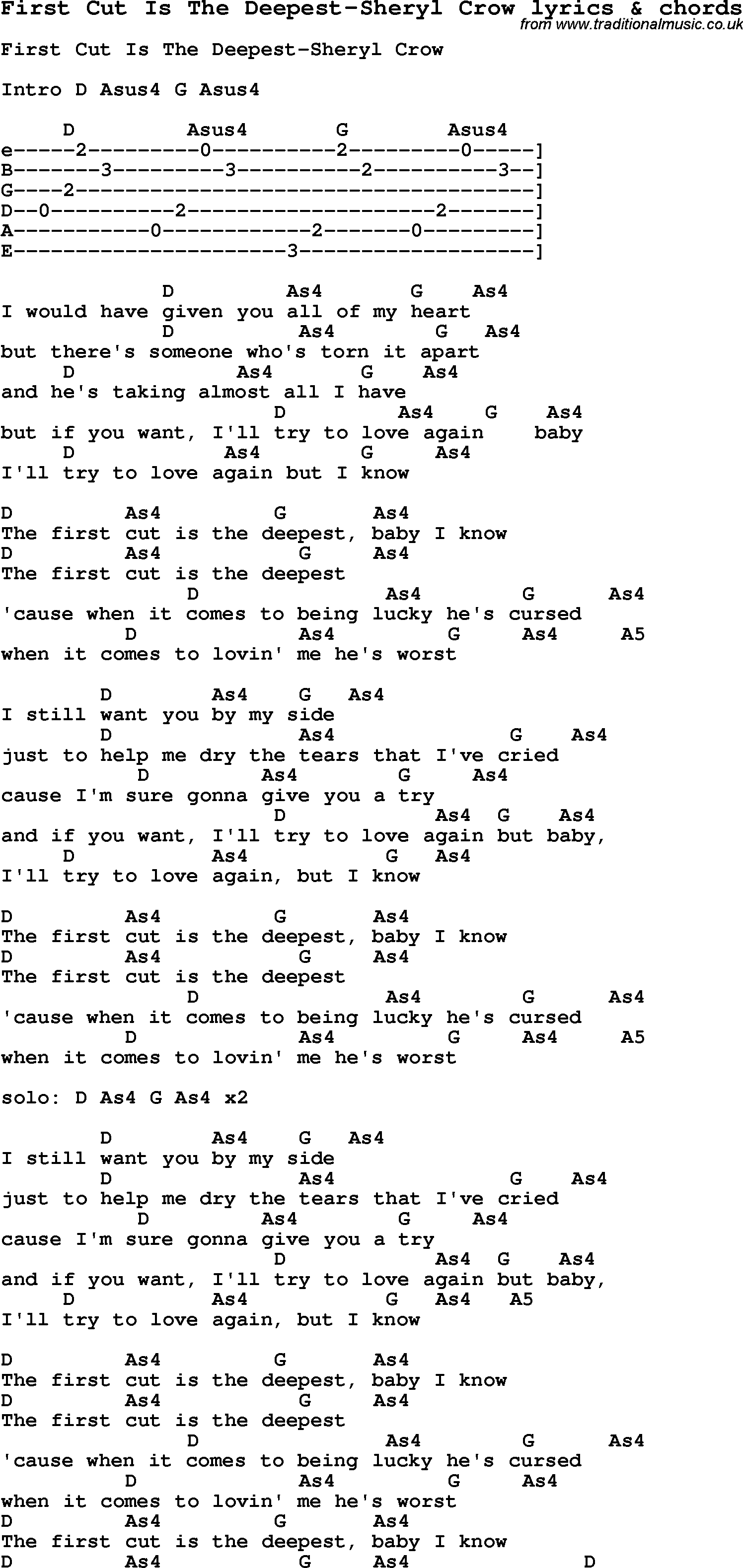

We need to talk about the structure. It’s a simple chord progression—mostly C, G, and F—but the way the melody climbs on the word "deepest" is what kills you.

🔗 Read more: Funny Memes and Pictures: Why Our Brains Still Crave These Digital Jokes

Stevens was a master of the "building" melody. He starts low, almost mumbling the admission that he’s hurt. By the time the chorus hits, he’s reaching for those higher notes, mimicking the way a person gets more desperate as they try to explain their feelings.

- The Original Vibe: Cat’s 1967 recording is actually quite fast and features a heavy soul influence.

- The P.P. Arnold Soul: She slowed it down, giving the lyrics room to breathe.

- The Stewart Swagger: He leaned into the "I'm trying to love again" aspect.

- The Crow Modernity: Clean, acoustic-driven, and focused entirely on the vocal delivery.

There’s a common misconception that Stevens wrote this about a specific famous girlfriend. He didn't. He wrote it while he was still living in his parents' flat above their restaurant, "Shaftesbury Pastries," in London. He was just a kid observing the world and feeling the weight of his own early romantic failures. He was also recovering from a bout of tuberculosis shortly after, which gave his later work—and his reflection on these lyrics—a much more spiritual, graveyard-adjacent tone.

The Philosophical Weight of a "Deep Cut"

What does it actually mean for a "cut" to be the deepest?

In psychology, there’s this idea called "imprinting." Your first major emotional attachment sets the blueprint for everything that follows. If that first experience is total abandonment, you spend the rest of your life looking for the exit sign in every room.

The first cut is the deepest lyrics act as a poetic explanation of attachment theory.

"I'll try to love again but I know / The first cut is the deepest."

The narrator is resigned. They aren't saying they won't love; they're saying they'll never love with that same naive, wide-eyed innocence again. You only get to be unscarred once. After that, you’re just a collection of healed over wounds trying to make a go of it.

How to Listen to the Song Today

If you’re going back to listen to this, don't just stick to the radio edits.

Go find Cat Stevens’ original 1967 version from the New Masters album. It sounds weirdly upbeat for such a depressing lyric. There’s a strange tension there—the music wants to dance, but the words want to cry.

Then, immediately flip to the P.P. Arnold version. It’s the version that Big Star’s Chris Bell reportedly obsessed over. It has this baroque-pop orchestration that makes the heartbreak feel cinematic.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Listener

To truly appreciate the craftsmanship here, try these steps:

- Isolate the Bassline: In the Stewart version, the bass drives the momentum, showing the "march" of moving on.

- Compare the Bridge: Notice how Stevens uses the bridge to pivot from the past to the future. It’s a masterclass in narrative songwriting.

- Read the Lyrics Without Music: If you read them as a poem, they lose the "pop" feel and become a very grim meditation on human connection.

The enduring power of these lyrics lies in their refusal to offer a happy ending. There is no "but then I met you and everything was fine." It’s just "I’m here, I’m trying, but I’m hurt." In a world of over-processed, "everything is great" pop music, that kind of grit is why we’re still talking about this song nearly sixty years later.

To understand the full impact of Stevens' work from this era, look into his transition from the pop-star "Steve Adams" persona into the folk icon Cat Stevens. This song was the pivot point. It was the moment he stopped writing what he thought the labels wanted and started writing what he actually felt. The results speak for themselves. Trace the evolution of the melody through his 1970s live performances to see how his own relationship with the song changed as he aged.