Accounting isn't just about spreadsheets and balancing the books. It’s about people. And people, honestly, are complicated. When we talk about the fraud triangle in accounting, we aren't just discussing a dry academic theory from the 1950s. We are looking at the exact moment a trusted employee decides to risk their entire career for a quick payout. It happens in small nonprofits. It happens at Enron. It happens because of three very specific ingredients that, when mixed together, create a perfect storm of financial disaster.

Donald Cressey, a noted criminologist, started looking into this decades ago. He interviewed hundreds of inmates—specifically "trust violators"—to understand why they snapped. He didn't find a bunch of career criminals. Instead, he found ordinary people who got caught in a vice. That’s the scary part. You probably work with someone right now who fits the profile, not because they’re "evil," but because the pressure is mounting.

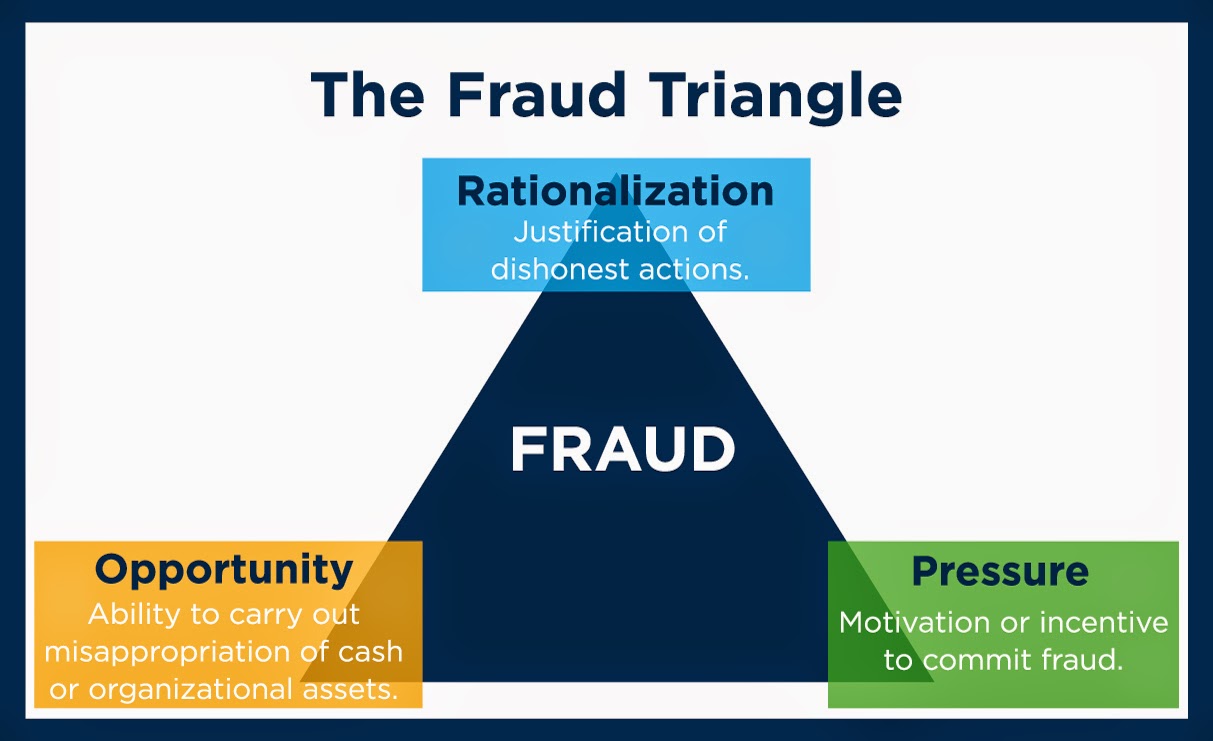

The Three Sides: Pressure, Opportunity, and Rationalization

Think of the fraud triangle in accounting like a fire. You need heat, fuel, and oxygen. Take one away, and the fire goes out. In the world of white-collar crime, those three sides are Pressure, Opportunity, and Rationalization.

The Pressure (The "Why")

Pressure is the motive. It’s the "why." Usually, it's a "non-shareable financial problem." Maybe a gambling addiction they’re hiding from their spouse. Or medical bills for a sick kid. Sometimes it's just pure, unadulterated corporate greed—the need to hit a quarterly bonus so they don't lose their beach house.

In the 2020s, we’re seeing a lot of "lifestyle creep" pressure. People want to look successful on social media, but their salary doesn't match their Instagram feed. This creates a secret desperation. They can't tell anyone they're broke, so they look for a "workaround" at the office.

The Opportunity (The "How")

This is where the accounting department usually fails. Opportunity is the "how." If a company has weak internal controls, they're basically leaving the vault open.

Imagine a small business where the same person writes the checks, signs them, and reconciles the bank statement. That’s a massive red flag. Why? Because nobody is looking over their shoulder. There’s no "segregation of duties." Most fraudsters don't start out planning a heist. They just notice a gap in the system. They think, "Wait, if I shift this entry to 'miscellaneous expenses,' nobody will ever notice." And they're usually right. At least at first.

The Rationalization (The "Self-Talk")

This is the most fascinating side. Fraudsters almost never think of themselves as criminals. They aren't "stealing"; they’re "borrowing."

Common rationalizations sound like this:

- "I'm overworked and underpaid; the company owes me this."

- "I'll pay it back as soon as I get my tax refund."

- "The CEO spends more on private jets than I'm taking in a year."

- "It’s for my family."

Once a person convinces themselves they aren't a "bad person," the internal barrier breaks. The fraud begins.

Real-World Messes: When the Triangle Completes

Look at the HealthSouth scandal in the early 2000s. It’s a textbook case. Richard Scrushy and his "family" of CFOs (five of them eventually pleaded guilty) cooked the books to the tune of $2.7 billion. The pressure? Keeping Wall Street happy and maintaining the stock price. The opportunity? A culture where questioning the boss was social suicide and internal controls were bypassed by the very people who created them. The rationalization? They believed they were "protecting" the employees' jobs by keeping the company's valuation high.

It’s never just one thing. It's a chain reaction.

In smaller cases, like the infamous Rita Crundwell theft in Dixon, Illinois, the triangle was even simpler. Crundwell stole $53 million from a town of 16,000 people.

- Pressure: She wanted to fund a world-class quarter horse breeding empire.

- Opportunity: She was the sole person in charge of the town's finances for decades. She opened a secret bank account that only she could access.

- Rationalization: She had worked there since she was a teenager and likely felt the town "belonged" to her in a way.

Why the Triangle is Morphing in the Digital Age

The fraud triangle in accounting is actually getting an upgrade. Some experts, like Wolfe and Hermanson, argue we need a fourth side: Capability. They call it the "Fraud Diamond."

Capability means having the actual brains and "positional power" to pull it off. You can have the pressure and the opportunity, but if you don't know how to navigate complex ERP systems or manipulate digital logs, you’re just going to get caught on day one. Modern fraud requires a certain level of technical savvy.

Also, we have to talk about the "Fraud Pentagon." This adds Arrogance and Competence. Arrogance is huge in C-suite fraud. It’s that "I’m too smart to get caught" mentality. We saw this with Sam Bankman-Fried and the FTX collapse. The lines between "innovative accounting" and "flat-out theft" got blurred by a sense of intellectual superiority.

Spotting the Red Flags (Before the Money Vanishes)

You can't read minds. You'll never know if an employee is feeling "pressure" at home unless they tell you. But you can watch for behavioral changes.

- The "No Vacation" Rule: If an accountant refuses to take a vacation, be suspicious. Why? Because if they leave for a week, someone else has to do their job—and that's when the "lapping" or "kiting" schemes are discovered. Fraud requires constant maintenance.

- Living Beyond Means: The clerk driving a brand-new Porsche on a $45k salary is a cliche for a reason. It’s usually the first sign something is wrong.

- Irritability and Defensiveness: When people are stressed about being caught, they snap. If someone gets weirdly aggressive when you ask for a specific receipt, take note.

How to Break the Triangle

You can't control an employee's personal life (Pressure) and you can't control their internal monologue (Rationalization). You can only control one thing: Opportunity.

Tighten the screws on internal controls.

Don't let one person hold the keys to the kingdom. Period. Segregate duties so that the person who approves a vendor isn't the person who cuts the check.

Conduct surprise audits.

Not just the scheduled ones. If people know a "spot check" could happen any Tuesday, the "Opportunity" side of the triangle starts to look a lot riskier.

📖 Related: Why Hartford Financial Services Stock Still Matters for Your Portfolio

Build an ethical culture from the top down.

If the CEO is fudging their expense reports, the staff will notice. Rationalization becomes much easier when "everyone is doing it."

Establish a whistleblower hotline.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) repeatedly finds that "tips" are the #1 way fraud is detected. Usually, a coworker knows something is up long before the auditors do.

What to Do Right Now

If you're running a business or managing a team, don't wait for a "gut feeling." Use the fraud triangle in accounting as a diagnostic tool. Look at your most "trusted" employees—the ones who haven't taken a day off in three years and have total control over the ledger. Those are your highest-risk points.

- Map your workflows. Literally draw out who touches the money and where it goes.

- Mandate vacations. Force people to step away from the books for two consecutive weeks.

- Check your "tone at the top." Ensure that your leadership isn't inadvertently creating "Pressure" by demanding impossible financial targets.

Fraud isn't just a cost of doing business. It's a failure of systems and a misunderstanding of human nature. By breaking the triangle, you aren't just protecting your cash—you're protecting your people from making the biggest mistake of their lives.