Imagine every single book you’ve ever touched. Now, imagine they’re all gone. Just vanished into smoke because some guy decided to set a harbor on fire or a mob got a little too angry one Tuesday afternoon. That’s the vibe people usually get when they talk about The Great Library of Alexandria. It’s become this massive symbol for "lost knowledge," like we’d all be living in space right now if some scrolls hadn't turned into ash. Honestly? It’s a bit more complicated than that.

History is messy.

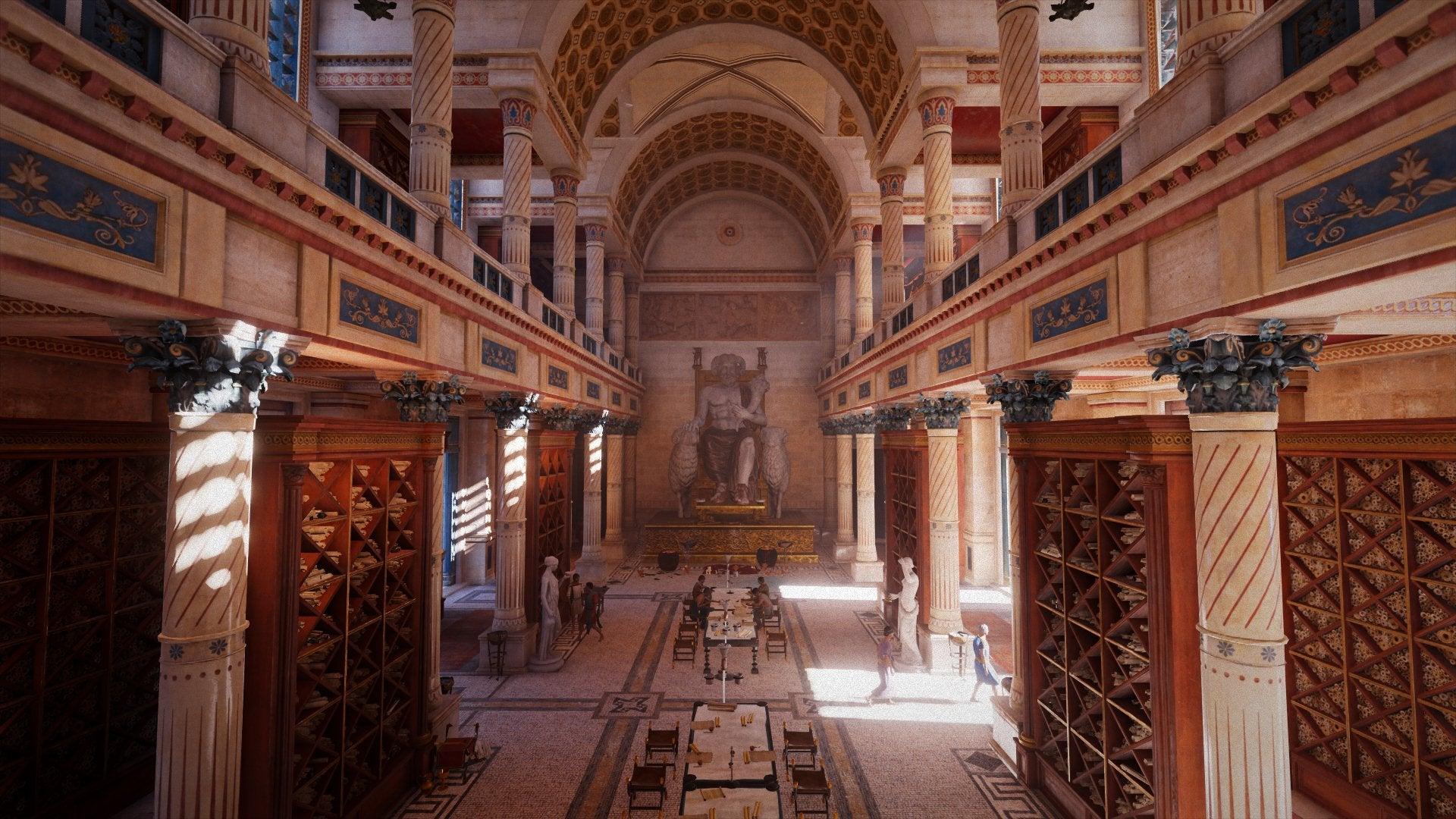

The Great Library of Alexandria wasn't just a building with dusty shelves; it was the world’s first real attempt at a "universal" database. It was the Google of the ancient world, but with physical scrolls and way more papyrus cuts. Founded around 300 BCE by Ptolemy I Soter—one of Alexander the Great’s generals—the place was built to house everything. Literally everything. Every play, every math theorem, every cook book from every corner of the known world.

How the Great Library of Alexandria Actually Worked

It’s easy to think of it like a modern public library where you show up, grab a chair, and quiet down. It wasn't that. It was part of the Musaeum, a research institute dedicated to the Muses. The kings of Egypt were obsessed. They didn't just buy books; they basically stole them.

📖 Related: Inn at the Quay: Why This New Westminster Spot Hits Different

There’s this famous story—it’s actually true—that any ship docking in Alexandria was searched. Not for drugs or contraband, but for books. If you had a scroll, the guards took it to the library. The scribes would copy it, keep the original, and give the owner back the copy. Rude? Yeah. But that’s how they built a collection that most historians, like Lionel Casson, estimate reached hundreds of thousands of scrolls.

The People Behind the Piles of Papyrus

You had the brightest minds in the Mediterranean living there rent-free.

- Eratosthenes? He calculated the circumference of the Earth within a few hundred miles using a stick and some shadows while working there.

- Aristarchus of Samos? He was the first to suggest the Earth goes around the sun, centuries before Copernicus.

- Callimachus? He basically invented the library catalog because, honestly, how else do you find one specific poem in a room with 400,000 scrolls?

These weren't just "librarians." They were the world's first data scientists. They spent their days arguing, editing, and trying to categorize the sum total of human experience.

The Big Myth: Who Actually Burned It?

Everyone wants a villain. People love to point a finger at Julius Caesar. In 48 BCE, Caesar was stuck in Alexandria helping Cleopatra in a civil war. He set fire to his own ships in the harbor to keep the enemy from cutting him off. The fire spread.

But did it destroy the whole thing?

Probably not. Most contemporary accounts suggest some warehouses near the docks burned, which definitely contained scrolls meant for export, but the main library likely survived. The "destruction" of the Great Library of Alexandria wasn't a single Saturday night bonfire. It was a slow, painful rot that lasted centuries.

📖 Related: Canada: What Most People Get Wrong About the 2nd Biggest Country in the World

Budget cuts are a tale as old as time. As the Roman Empire got messy and Alexandria became a hotspot for religious riots, the library just stopped being a priority. By the time the emperor Caracalla stopped the library's funding in the 3rd century CE, the "Great" library was probably already a shell of itself.

The Religious Riots and the Final Blow

By the late 4th century, things got ugly. The Emperor Theodosius I banned paganism. The Serapeum—a "daughter library" that held many of the scrolls—was destroyed by a Christian mob led by Bishop Theophilus in 391 CE. They saw the scrolls as pagan propaganda.

Then you have the story of the Arab conquest in 642 CE. Some later writers claimed Caliph Omar ordered the remaining scrolls to be burned to heat the city's baths. Modern historians like Bernard Lewis generally consider that story a myth or at least a massive exaggeration. By then, there probably wasn't much left to burn.

The tragedy isn't that one guy with a torch ruined everything. The tragedy is that we stopped caring. We stopped funding the scribes. We stopped repairing the roof. The Mediterranean humidity and the bugs did more damage over 600 years than Caesar ever did in one night.

What Did We Actually Lose?

This is where it gets depressing. We have "titles" of books we’ll never read. We know Sophocles wrote over 120 plays. We have seven. Seven!

We lost the history of the Etruscans. We lost thousands of years of Egyptian records that were written in Greek. We lost scientific observations that might have jump-started the Renaissance a millennium early.

But it’s not all doom.

A lot of what was in Alexandria survived because people copied it and took it elsewhere. The reason we have Homer or Aristotle today is because the work done in Alexandria preserved those texts long enough for them to be moved to Constantinople or kept by scholars in the Islamic Golden Age.

Visiting the Site Today: The Bibliotheca Alexandrina

If you go to Alexandria today, you won’t find the original columns. You’ll find the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. It’s a massive, sun-disk-shaped building opened in 2002. It’s stunning. It’s got space for eight million books and a massive reading room that angles toward the sea.

✨ Don't miss: Why China's Glass Bridge Obsession Isn't Just for Tourists

Walking through it feels like a weird sort of apology to the past. The walls are covered in characters from every known alphabet. It’s a high-tech marvel, but it sits on the ghost of the most important intellectual experiment in history.

How to Explore this History Yourself

If you’re a history nerd or just someone who hates losing their browser tabs, there are ways to connect with this lost world without a time machine.

1. Go to the Source (Sorta)

The new Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Egypt is a must-visit. Don't just look at the outside. Go into the Manuscript Museum in the basement. They have digital versions of ancient texts and some genuine fragments that make the hair on your arms stand up.

2. Read the "Survivors"

Check out The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World by Roy MacLeod. It’s academic but readable. It breaks down the "who's who" of the library without the fluff.

3. Digital Archeology

Use the Perseus Digital Library. It’s a project by Tufts University that’s trying to do exactly what the Ptolemies did: collect every classical text in one place. It’s free, and you won’t get your scrolls confiscated by Egyptian harbor guards.

4. Look for the "Palimpsests"

A lot of ancient knowledge was found because monks scraped the "old" Greek writing off parchment to write prayers over it. Modern X-ray technology (like the Archimedes Palimpsest project) is literally reading "lost" books through the layers of newer ones.

The Great Library of Alexandria taught us one brutal lesson: information is fragile. It’s not just about keeping the books; it’s about keeping the culture that values them. When a society decides that learning isn't worth the tax dollars or that "those books" are dangerous, the library starts burning before anyone even lights a match.

Check the provenance of your sources. In an era of digital rot and link-death, the best way to honor the Library is to be a bit of a librarian yourself. Archive what you love. Support local libraries. Don't assume the internet will remember everything for you. It won't.