Track maps aren't just lines on a screen. They represent the difference between a minor inconvenience and a flooded living room. If you’re looking at a hurricane Erin path map, you’re actually looking at a bit of meteorological history that’s surprisingly complicated. Why? Because "Erin" has been the name of several Atlantic storms, but two in particular—1995 and 2001—changed how we think about forecasting. One hit the Florida coast like a stubborn guest who wouldn't leave, while the other pulled a dramatic U-turn in the middle of the Atlantic that left everyone breathing a sigh of relief.

It’s easy to get lost in the spaghetti models.

When a storm is churning out there, the map is everything. For Erin in 1995, that map was a source of massive frustration for the National Hurricane Center (NHC). It didn't follow the "script." Usually, you expect a storm to pick a direction and commit, but Erin was erratic. It clipped the Bahamas, smashed into Vero Beach, crossed the entire Florida peninsula, popped out into the Gulf of Mexico, and then decided to hit the Florida Panhandle for a second helping of chaos. People were exhausted.

👉 See also: Weather Radar Long Island NY: Why Your App Is Probably Lying to You

Tracking the Chaos: The 1995 Hurricane Erin Path Map

Looking back at the data from August 1995, the hurricane Erin path map shows a track that looks like a jagged staircase. It wasn't a smooth curve. It started as a tropical wave off the coast of Africa—nothing unusual there—but by the time it reached the Bahamas, it was clear this wasn't going to be a "fish storm" that just stayed at sea.

The first land strike happened near Vero Beach, Florida. Erin was a Category 1 hurricane then. You might think a Cat 1 isn't a big deal compared to a monster like Andrew, but Erin proved that rain and persistence matter just as much as wind speed. As it moved across central Florida, the storm actually stayed pretty organized. Usually, friction from the land tears these things apart. Erin? Not so much. It kept its structure, dumped buckets of rain on Orlando, and emerged into the Gulf of Mexico near Tampa.

That’s where the map gets really interesting.

Forecasters thought it might weaken or head toward Louisiana. Instead, it strengthened. It became a Category 2 hurricane with 100 mph winds before slamming into Pensacola. If you look at the 1995 hurricane Erin path map today, you can see that double-hit clearly. It’s a reminder that Florida isn't just one target; it's a long, skinny peninsula that can get hit from both sides by the same exact storm. Honestly, it’s kind of a worst-case scenario for emergency management.

Why the 1995 Path Was So Hard to Predict

Back then, the technology wasn't what it is now. We didn't have the sophisticated ensemble modeling we use in 2026. Forecasters like Max Mayfield were working with much coarser data. The "steering currents"—those high-altitude winds that push hurricanes around like corks in a stream—were weak. When steering currents are weak, hurricanes wobble. They drift. They do weird stuff.

The 2001 Shift: A Different Kind of Mapping Lesson

Fast forward to 2001. Another Erin.

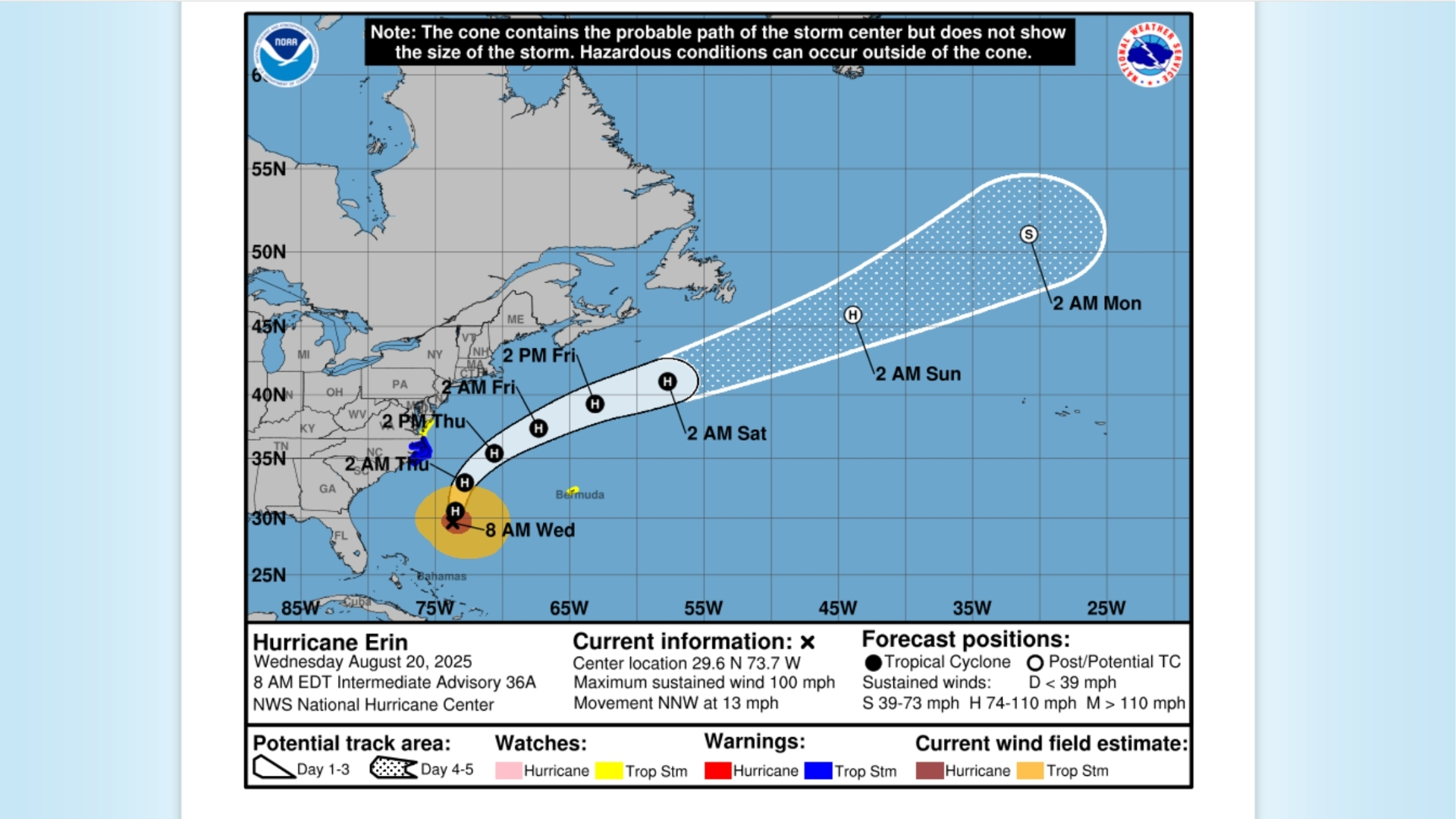

This time, the hurricane Erin path map looked totally different. It was a much stronger storm, peaking at Category 3 strength with 120 mph winds. For a few days in September, the entire East Coast was on edge. If you look at the track from September 8th to September 10th, 2001, the "cone of uncertainty" was draped right over New England and the Canadian Maritimes.

But then, a miracle of physics happened.

A large trough of low pressure moved off the U.S. coast. In meteorological terms, this acted like a giant vacuum cleaner, sucking Erin away from the coast and pulling it northeast. The map shows a sharp, almost 90-degree turn. It’s one of the most famous "close calls" in Atlantic hurricane history. While the storm eventually hit Newfoundland as a much weaker system, the 2001 map is a classic example of a "recurve."

Understanding the "Spaghetti" on Your Map

When you look at a modern hurricane Erin path map, or any storm map for that matter, you’re likely seeing multiple lines. These are the GFS (American) and the ECMWF (European) models.

✨ Don't miss: The Annunciation Catholic School Shooting: What Actually Happened in Havelock

- The GFS: Often a bit faster and sometimes more "aggressive" with landfalls.

- The Euro: Generally considered the gold standard for track accuracy, though it’s not perfect.

- HWRF: A specialized model that focuses more on how intense the winds will get rather than just where the center is going.

The reality is that no single line is "correct." The path is a probability. When Erin was active in 1995, the "cone" didn't exist in the way we see it on TV today. The NHC only started using the graphic cone in 2002. Before that, it was just a line with some shaded areas. We’ve come a long way in how we visualize these threats, but the core problem remains: hurricanes are fluid, dynamic systems that can change their mind in an hour.

The Impact Beyond the Lines

Maps are great for seeing where the center of the storm goes, but they’re kind of terrible at showing the actual danger.

Take the 1995 Erin again. The path went right over the Florida Panhandle. But the damage? It was spread out for hundreds of miles. In places like Mary Esther and Navarre Beach, the storm surge was the real story, not the wind. A hurricane Erin path map doesn't show you the 6-to-7-foot surge that pushed Gulf water into people's garages. It doesn't show the tornadoes that spun off in the outer bands, miles away from the "line."

This is a major point of confusion. People see the line on the map and think, "Oh, it's 50 miles away, I'm fine."

You're not fine.

The right-front quadrant of a hurricane is the "dirty side." That's where the strongest winds and the highest surge usually live. In 1995, if you were on the right side of Erin's path, you got hammered. If you were on the left, it was just a rainy day. The map tells you the destination, but it doesn't always tell you the size of the footprint.

Practical Steps for Reading Future Hurricane Maps

It’s 2026. We have better satellite imagery than ever. But you still need to know how to interpret what you’re seeing. Don't just look for the name "Erin" or whatever the current storm is—look at the atmospheric context.

1. Focus on the Cone, Not the Line

The center of the storm stays within that shaded cone about 67% of the time. That means there is a 33% chance it could go outside the cone. Never assume you're safe just because the thin black line isn't touching your city.

2. Check the "Arrival of Tropical Storm Force Winds" Map

This is actually more important than the path map. It tells you when your window for preparation closes. Once those 39+ mph winds start, you can't be outside on a ladder putting up shutters. It’s too dangerous.

3. Look for "Stationary" Warnings

If a path map shows the storm dots getting closer together, it means the hurricane is slowing down. A slow hurricane is a flood machine. The 1995 Erin moved at a decent clip, but if it had stalled, Florida would have been underwater.

4. Respect the Intensity Forecast

The hurricane Erin path map for 2001 showed a powerful Cat 3. Even though it stayed offshore, the swells it pushed toward the beach caused dangerous rip currents for a thousand miles. You don't need a direct hit to feel the effects.

What These Maps Teach Us About Risk

Basically, looking at historical data like the Erin tracks proves that every storm is a unique beast. You can't use 1995 to predict 2026. The ocean is warmer now. The atmosphere holds more moisture. But the fundamental physics of the "recurving path" or the "peninsula crosser" remain the same.

If you're looking at a map and you see a storm heading your way, the best thing you can do is look at the "wind speed probabilities" rather than just the track. It gives a much more realistic view of your personal risk.

Stay weather-aware. Don't fixate on a single model run. The "spaghetti" changes every six hours for a reason—it’s updated with new data from weather balloons and "Hurricane Hunter" aircraft that fly directly into the eye. They’re the real heroes who make these maps possible in the first place.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Download the NHC Data: Go to the National Hurricane Center archives to see the full, high-resolution 1995 and 2001 track datasets. It’s a great way to see how much the science has evolved.

- Build Your "Go-Kit" Early: Don't wait for a path map to show a storm heading for your zip code. By then, the water and batteries are gone from the shelves.

- Check Your Elevation: Use a local GIS map to see how high your house sits above sea level. This matters more than the wind speed when a storm like Erin is pushing water inland.