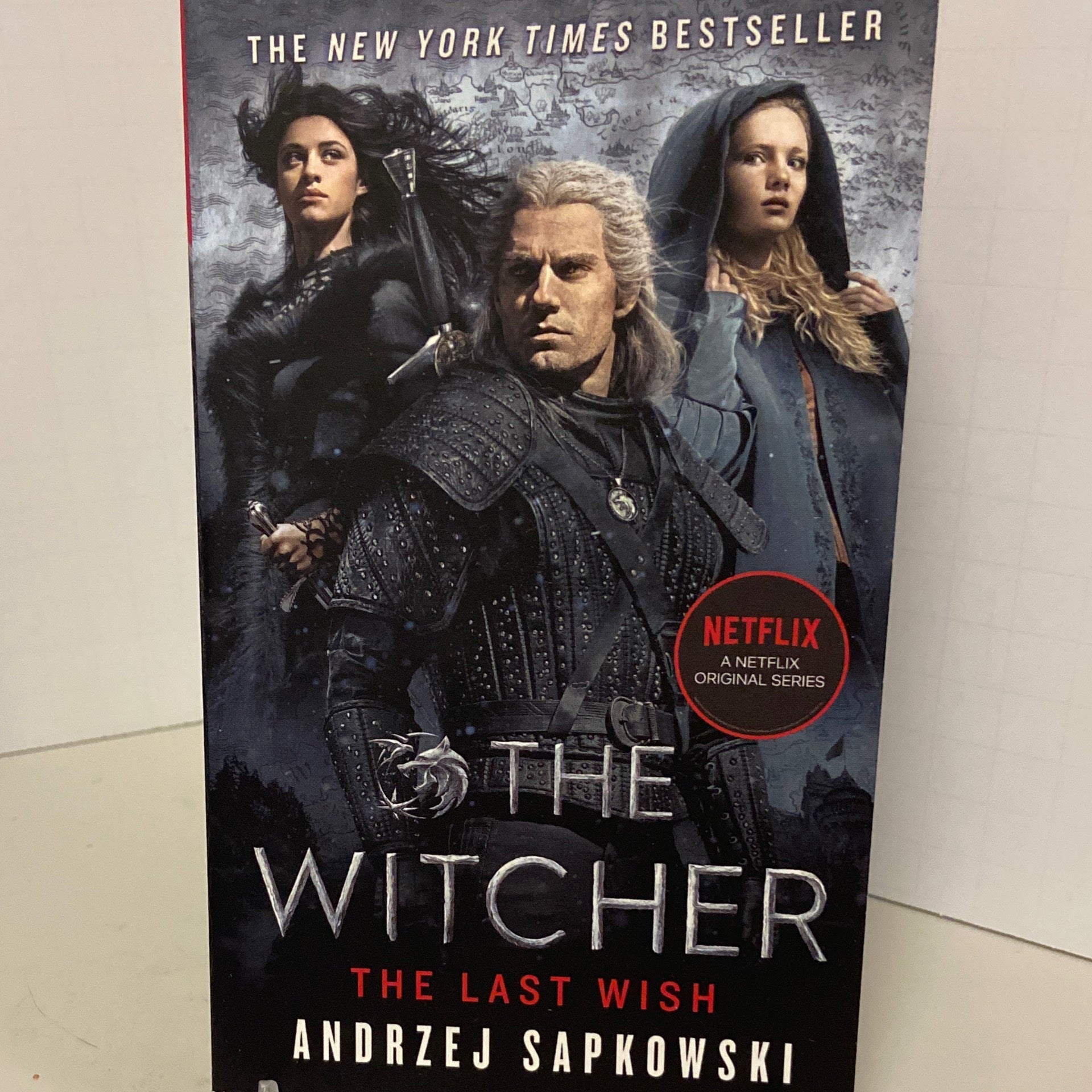

You’ve probably seen the yellow eyes. Maybe you’ve heard the gravelly voice of Henry Cavill or spent two hundred hours playing The Wild Hunt on your console while ignoring your actual responsibilities. But here’s the thing: before the Netflix checks and the CD Projekt Red masterpieces, there was just a Polish guy named Andrzej Sapkowski writing short stories for a magazine called Fantastyka in the mid-1980s. The Last Wish: Introducing the Witcher wasn't actually the first book published in Poland, but it’s the definitive starting point for anyone who wants to understand why Geralt of Rivia is a cultural icon.

It’s messy. It’s dark. Honestly, it’s a bit weird if you’re used to the shiny, noble knights of Tolkien. Geralt isn't out to save the world; he’s out to make enough coin to feed his horse, Roach, and maybe get a decent meal that doesn't taste like swamp water.

Why The Last Wish: Introducing the Witcher Hits Different Than Modern Fantasy

Most fantasy novels start with a map and a prophecy. Sapkowski didn't care about that. In The Last Wish: Introducing the Witcher, he basically takes the fairy tales your grandma told you—Snow White, Beauty and the Beast, Sleeping Beauty—and drags them through the mud. It turns out "Beauty" might just be a vampire, and "Snow White" is a cynical bandit leader with a grudge and a very sharp sword.

Sapkowski uses a frame story called "The Voice of Reason" to tie everything together. Geralt is recovering in a temple after a nasty fight with a striga. Between his conversations with the priestess Nenneke, he remembers his past adventures. This structure is brilliant because it lets the reader see the "greatest hits" of a Witcher’s life without needing a 600-page chronological slog. You get the world-building through osmosis. You learn about the "Trial of the Grasses"—the brutal alchemical process that mutates children into monster hunters—not through a textbook chapter, but through the scars on Geralt’s body and the way people look at him with a mix of fear and disgust.

He’s a mutant. People need him to kill the monsters under their beds, but they don't want him at their dinner tables. That tension is the heartbeat of the series.

The Short Stories That Changed Everything

If you're looking for the soul of the series, look at "The Lesser Evil." It’s the story that gave Geralt his nickname, the Butcher of Blaviken. It’s a tragedy. There are no heroes. Geralt is forced to choose between two villains, and by choosing what he thinks is the "lesser" evil, he ends up hated by the very people he tried to protect. It’s a gut punch. It sets the tone for the entire saga: sometimes, there is no right answer, only a series of bad options.

Then you’ve got "A Grain of Truth." It’s a reimagining of Beauty and the Beast where the Beast is Nivellen, a man cursed for raping a priestess. It’s uncomfortable and nuanced. It’s not a Disney movie.

And we have to talk about the title story, "The Last Wish." This is where we meet Yennefer of Vengerberg. She’s a sorceress, she smells like lilac and gooseberries, and she’s basically a force of nature. Their meeting involves a djinn, a lot of property damage, and a magical wish that ties their fates together in a way that fans still argue about decades later. Was it real love? Or was it just the magic? Sapkowski leaves it just vague enough to be frustratingly beautiful.

The World-Building Isn't What You Think

A lot of people think The Witcher is just "Middle-earth but with more swearing." That’s a mistake. Sapkowski’s world is deeply rooted in Slavic mythology, but it’s also a commentary on post-war Poland and the complexities of the Cold War era. You see themes of racism, environmental destruction, and the corruption of institutions. The elves aren't ethereal beings living in golden woods; they’re disenfranchised rebels living in poverty because humans stole their land.

The monsters aren't always the ones with claws. Often, the "monsters" are just animals acting on instinct, while the "men" are the ones committing atrocities for gold or power. Geralt often finds himself sympathizing with the creature he was hired to kill. That’s the irony of his profession. He’s supposed to be stripped of emotion by his mutations, yet he’s frequently the most moral person in the room.

Understanding the Witcher’s Code (or Lack Thereof)

Geralt talks a lot about "The Witcher’s Code." He uses it to get out of awkward political situations or to justify why he won't take a certain contract. Here’s a secret: there is no code. He made it up. It’s a shield. By claiming he’s bound by a rigid set of professional rules, he protects his own autonomy. He’s a freelancer in a world of kings and emperors, and that’s a dangerous place to be.

✨ Don't miss: Cardi B Song Outside: The Drama You Definitely Missed

- Silver for Monsters: One sword is silver for magical beings.

- Steel for Humans: The other sword is steel for the mundane threats.

- Signs: Simple combat magic like Aard (a kinetic blast) or Igni (fire).

- Potions: Toxic brews that would kill a normal human but give Geralt cat-like reflexes.

The Translation Hurdle and Global Success

For a long time, The Last Wish: Introducing the Witcher was a cult hit limited to Eastern Europe. The English translation didn't even hit shelves until 2007, timed to the release of the first video game. Danusia Stok, the translator, had the massive task of capturing Sapkowski’s specific brand of dry, cynical humor. In Polish, the dialogue is snappy and full of archaic slang. In English, it still works, but you can tell there’s a layer of cultural grit that’s hard to fully port over.

Despite the delay, the book exploded. Why? Because it felt "real" in a way high fantasy often doesn't. Geralt worries about his boots wearing out. He deals with bureaucracy. He gets tired. He’s a blue-collar hero.

Misconceptions You Should Probably Drop

- It’s not a trilogy. People see the three big games and think the books follow that. Nope. The books are a series of short stories followed by a five-book "Saga" (and a later standalone novel, Season of Storms).

- Geralt isn't a superhero. He can be beaten. He gets hurt. In the books, he spends a significant amount of time being broke and limping.

- The games aren't canon. Andrzej Sapkowski has been very clear about this. The games are "high-budget fan fiction" (his words, mostly). They’re a sequel to the books, but if you want the "true" story, the books are the only source.

Actionable Steps for New Readers

If you're ready to dive in, don't just grab a random book with Geralt on the cover. Follow this path to get the best experience:

- Start with The Last Wish. Do not skip to the novels. You need the character introductions here to understand the emotional stakes later.

- Read Sword of Destiny second. It’s another collection of short stories, but it introduces Ciri, who is arguably more important to the overarching plot than Geralt himself.

- Pay attention to the names. Sapkowski loves naming characters after real historical figures or tweaking folk names. It adds a layer of depth if you’re a history nerd.

- Don't expect a happy ending. This isn't that kind of series. It’s about the "bittersweet."

The genius of The Last Wish: Introducing the Witcher lies in its refusal to be simple. It challenges the reader to look past the silver hair and the swords to see a man trying to maintain his humanity in a world that denies he has any. Whether you’re here because of the games, the show, or just a recommendation from a friend, the book is the foundation. It’s where the grit started. And honestly, it’s still the best place to see Geralt do what he does best: survive.

To get the most out of your reading, track the recurring theme of "destiny" versus "choice." Geralt claims he doesn't believe in destiny, yet his entire life is shaped by it. Witnessing how he fights against the inevitable is what makes him one of the most compelling characters in the history of the genre.

Check your local library or a used bookstore for the Orbit-published paperbacks; they’re the most common and feature the classic cover art that doesn't rely solely on game renders. Once you finish the short stories, move immediately into Blood of Elves to begin the main saga.