You’ve probably seen those old textbooks. They show a massive, solid blob of green covering almost all of North America, signaling where wolves used to roam before we decided they were "pests." It's a bit depressing, honestly. But if you look at a modern map of gray wolf range, the story gets a lot more complicated—and way more interesting. It isn’t just a story of loss; it’s a messy, ongoing saga of comeback stories, legal battles, and wolves literally walking hundreds of miles to find a new home.

Wolves are survivors.

They don't care about state lines or international borders. A wolf tagged in Michigan might end up in Ontario, or a lone disperser from Oregon might suddenly pop up in the California Sierras, baffling local ranchers and delighting biologists. When we talk about their "range," we aren't talking about a static line on a map. We’re talking about a living, breathing geography that changes every time a new pup survives the winter or a pack gets delisted from the Endangered Species Act.

What the Current Map Actually Tells Us

Most people think wolves are only in Yellowstone. That’s a huge misconception. While the 1995 reintroduction in the park is the most famous event in conservation history, the map of gray wolf range today spans across the Great Lakes, the Northern Rockies, the Pacific Northwest, and even small pockets of the Southwest.

The Great Lakes region is actually the heavyweight champion here. Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan hold a massive chunk of the lower 48’s wolf population. In Minnesota alone, wolves never truly went extinct; they held on in the deep woods of the northeast when the rest of the country was "wolf-free." Today, they’ve pushed south, creeping closer to the suburbs of Minneapolis than most residents realize. It’s a stable, rugged population that acts as a reservoir for the entire region.

💡 You might also like: Exactly How Many Days Since October 12 2024? The Math and Why It Matters

Then you have the West. This is where the maps get controversial.

In the Northern Rockies—Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—the range is basically "full." Biologists call this "carrying capacity." There’s only so much elk and so many mountains to go around. Because of this, we’re seeing wolves spill over. They’re moving into Washington state, where packs like the Lookout Pack changed the map forever in 2008. They’re moving into Oregon. And, most recently, they’ve officially returned to Colorado through a voter-mandated reintroduction program.

It’s a patchwork. It isn't a continuous blanket of wolves. It’s a series of "islands" of habitat connected by thin corridors that wolves use to travel. If a wolf wants to get from the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the Cascade Range, it has to dodge highways, ranches, and towns. That "map" in their heads is a gauntlet.

The Massive Gap in the Middle

Why is the center of the US a giant blank spot?

If you look at a map of gray wolf range, there is a glaring absence in the Great Plains and the East Coast. Historically, gray wolves (Canis lupus) lived from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Today, you won't find a breeding pack in New York, Pennsylvania, or Ohio.

Is the habitat there? Sorta.

The Adirondacks in New York have plenty of deer, but the problem is connectivity. For a wolf to get from the Canadian border or the Great Lakes to the Northeast, it has to cross some of the most human-congested landscapes on Earth. Biologists like those at the Center for Biological Diversity often point out that while the habitat is physically there, the "social tolerance" isn't. People aren't used to living with large carnivores in the suburbs of New Jersey.

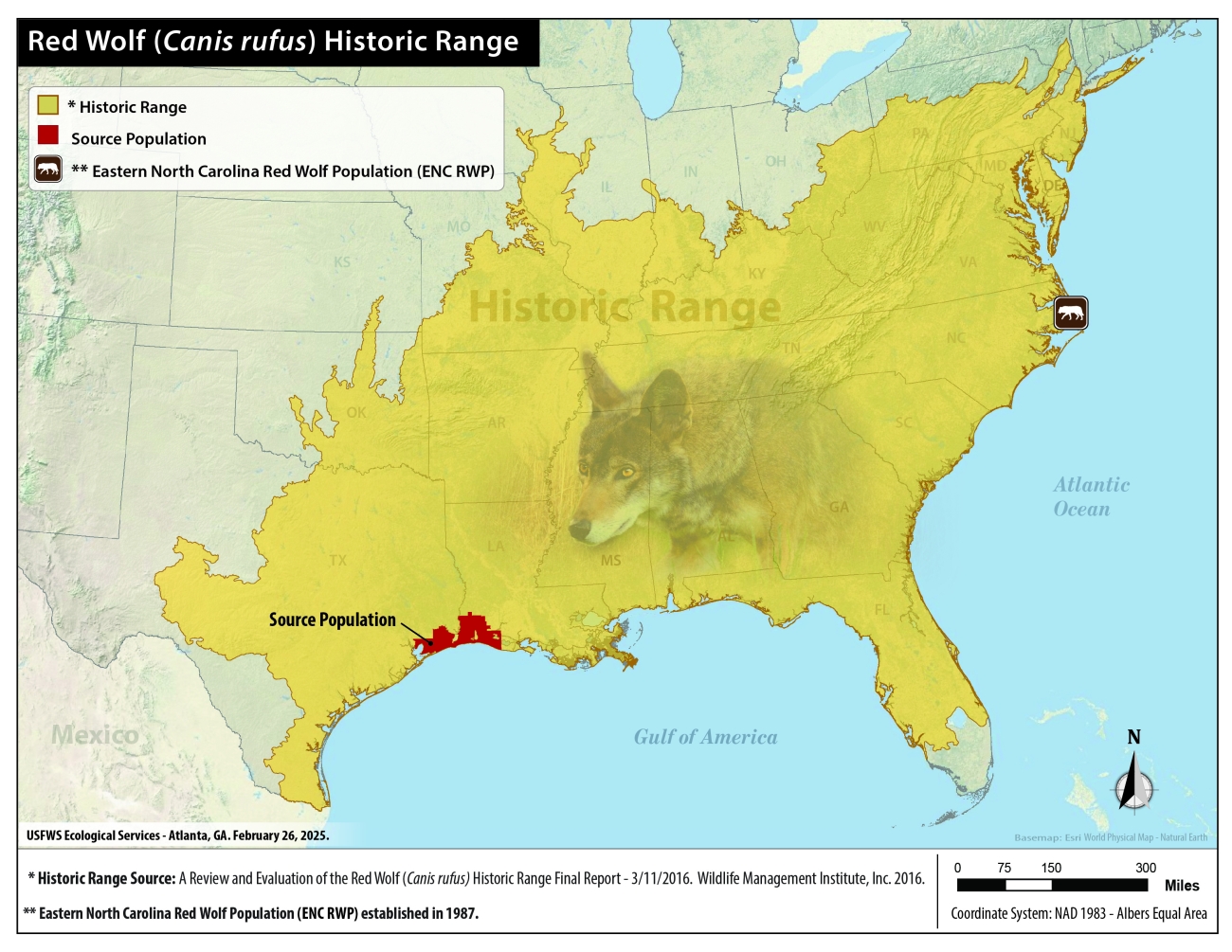

Also, we have to talk about the "Red Wolf" and the "Eastern Wolf." In the Southeast, the Red Wolf (Canis rufus) is a separate, critically endangered species clinging to life in North Carolina. In the Northeast, what people often call "brush wolves" or "coywolves" are actually hybrids. These animals fill the ecological niche of the wolf, but on a formal map of gray wolf range, they don't count. It’s a taxonomic headache that keeps scientists arguing in journals for decades.

Why the Lines Keep Moving

Wolves are naturally "dispersers."

When a young wolf hits two or three years old, they get the itch to leave. They want their own territory. They want a mate. So, they start walking. This is how the range expands naturally. We’ve seen wolves from the Great Lakes trek all the way to Nebraska. We’ve seen "OR-7," a famous wolf from Oregon, walk thousands of miles into California, eventually founding the first pack there in nearly a century.

When you look at a map, you have to distinguish between "Resident Range" and "Dispersal Events."

- Resident Range: Where packs are breeding, raising pups, and holding territory year-over-year.

- Dispersal Events: Where a lone wolf showed up, got caught on a trail cam, and maybe moved on or died.

Just because a wolf was seen in Kansas doesn't mean Kansas is part of the "range" yet. It means the map is being tested.

The Politics of the Map

You can't talk about wolf geography without talking about the law. The map changes based on who is in office and what the courts say. When wolves are under federal protection, they are allowed to expand into new areas with minimal human interference (meaning you can’t shoot them for being on your land).

✨ Don't miss: Coos Bay 10-Day Forecast: What Local Residents Actually Expect

When they are delisted and management handed to the states, the map often shrinks or stabilizes.

In Idaho and Montana, state laws have become much more aggressive regarding wolf hunting and trapping. The goal of these states isn't to wipe wolves out—usually—but to keep them within specific zones to protect livestock and elk herds. This creates a "hard edge" on the map of gray wolf range. The wolves might want to move into a certain valley, but if that valley has a high "take" rate from hunters, the range stops right at the treeline.

Then there’s the Mexican Gray Wolf in Arizona and New Mexico. This is a subspecies (Canis lupus baileyi), and their map is strictly fenced in by "recovery areas." They are kept in a specific zone, and for years, if they crossed an invisible line (Interstate 40), they were captured and moved back. It’s a managed wildness. It’s not a natural range; it’s a political one.

Misconceptions: What the Map Doesn't Show

One big mistake people make is thinking that a large range means the wolves are "taking over."

In reality, wolf density is usually pretty low. A single pack of 6 to 10 wolves might require 200 to 500 square miles of territory. So, a map that shows wolves covering half of a state might only represent a few hundred animals total. They are spread thin. They need space.

Another thing? The "Historic Range" argument.

Some activists want the map to look like it did in 1700. That’s never going to happen. The American West is paved. It’s fenced. It’s full of cows. While wolves are adaptable—they can live almost anywhere there is enough meat—the modern map is a compromise. It’s a negotiation between biological needs and human lifestyle.

Real Data: Looking at the Numbers

If you want to see the most accurate, up-to-date data, you shouldn't look at a generic Google Image search. You need to look at the state-specific reports.

- Minnesota: Roughly 2,700 wolves. They occupy the entire northern third of the state.

- Wisconsin/Michigan: Around 1,200 combined. They are mostly in the Northwoods and the Upper Peninsula.

- Northern Rockies: Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming have about 2,500-3,000 wolves.

- Oregon/Washington: Each has around 150-200 wolves and growing.

- Arizona/New Mexico: The Mexican Wolf population is hovering around 250 in the wild.

These numbers fluctuate every year. A bad winter or a change in hunting quotas can shift these totals by 10% or 20% in a single season.

Actionable Insights for Tracking Wolf Range

If you're interested in where wolves are actually moving, don't just wait for a news report. You can be proactive about understanding this landscape.

Use Interactive State Maps

Most state Fish and Wildlife departments (like WDFW in Washington or CPW in Colorado) maintain "Wolf Activity" maps. These are far more accurate than national ones. They often show "confirmed" vs. "unconfirmed" sightings. Check these monthly if you live in a wolf-adjacent area.

Follow the "Collar Data"

While the public usually doesn't get real-time GPS coordinates (for the wolves' safety), many research groups release "annual movement" summaries. Seeing the path of a single dispersing wolf can teach you more about the map of gray wolf range than any static infographic. It shows you the highways they cross and the rivers they swim.

Understand the "Recovery Zones"

If you are a hiker or hunter, learn the difference between a "Recovery Zone" and "Experimental Population" areas. In some parts of the map, wolves have different legal status. Knowing this helps you understand why a wolf pack is allowed to stay in one forest but might be "removed" from another.

Support Connectivity

The biggest threat to the wolf map isn't hunting; it's fragmentation. Supporting "Wildlife Overpasses" and "Green Corridors" is the only way the map will ever truly reconnect the Great Lakes to the Rockies. Without these bridges, the populations stay isolated and genetically stagnant.

The map is a living document. Every time a wolf howls in a place it hasn't been heard in a century, the lines move just a little bit. It’s a testament to a species that refused to go quiet, even when we tried our best to erase them from the page. If you want to stay informed, keep your eyes on the borderlands—the places where forest meets farm—because that’s where the next chapter of the map is being written right now.

Keep an eye on the Voyager Wolf Project or the Wolf Conservation Center for the most nuanced takes on how these territories are shifting in real-time. They do the boots-on-the-ground work that turns raw data into the maps we rely on.

To stay truly updated on the status of these animals, check the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s annual reports on the recovery of the gray wolf. These documents are dry, sure, but they contain the verified census data that actually defines the legal boundaries of where wolves can and cannot be. You might also want to look into the work of the Western Wolf Coalition, which focuses on the specific challenges of range expansion in the Pacific Northwest and the unique "social" maps of those local communities. Understanding the map is about more than just dots on a page; it’s about understanding the conflict and cooperation between two apex predators: wolves and us.