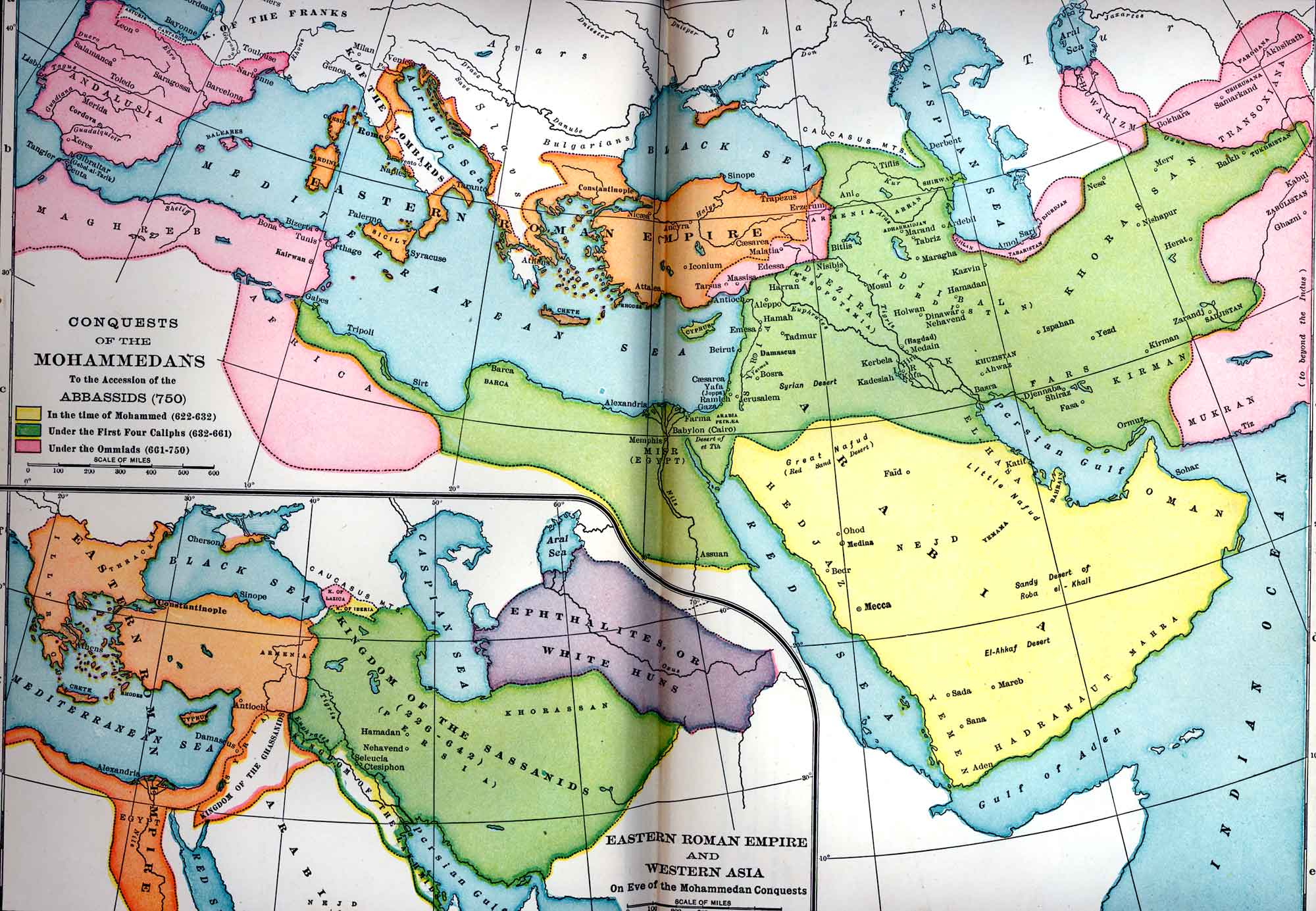

Look at a map of the expansion of Islam and you’ll see these massive, sweeping arrows of green. They surge out of the Arabian Peninsula, swallowing Egypt, Iran, and Spain in what looks like a single, unstoppable blink of an eye. It’s intimidating. It looks like a simple story of "conquest," but honestly, the reality on the ground was way messier and, frankly, much more interesting than those flat colors on a page suggest.

History is loud.

When we look at the Rashidun and Umayyad eras, we’re looking at one of the fastest geopolitical shifts in human history. We're talking about a movement that started in 632 CE and, by 750 CE, stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indus River. But a map doesn't show you the tax records. It doesn't show you the years—sometimes decades—where life for a farmer in Damascus or a merchant in Samarkand didn't actually change all that much despite having a new ruler.

Why the Map of the Expansion of Islam Isn't Just About War

Most people think this map is just a record of battles.

That's a mistake.

🔗 Read more: Wilmington Delaware on a Map: What Most People Get Wrong

While the military campaigns under commanders like Khalid ibn al-Walid were undeniably brilliant—specifically his maneuvers at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636—the "expansion" part of the map also represents a massive shift in trade and language. You've got to understand that the Byzantine and Sassanid Empires were basically exhausted. They had been punching each other for centuries. When the Arab armies showed up, they weren't just fighting soldiers; they were stepping into a power vacuum.

If you look at the map between 632 and 661 CE (the Rashidun period), the growth is concentrated in the Levant, Egypt, and Persia. This wasn't just "taking over." In many cases, it was a negotiation. Take the surrender of Jerusalem to Caliph Umar. He didn't burn the city. He signed the Pact of Umar, which, while establishing the dhimmi status (protected non-Muslim subjects), actually allowed many locals more religious freedom than they had under the previous Byzantine rule.

Geography played a huge role.

The desert was a highway for the Arab forces. They used it like a sea. Their camels gave them a logistical edge that the heavy, road-bound Byzantine infantry couldn't match. They could strike and then retreat into the dunes where no one could follow. It was 7th-century blitzkrieg.

The Umayyad Push and the Limits of the Green

By the time the Umayyad Dynasty took over in Damascus, the map of the expansion of Islam started looking truly global. This is the era where the map reaches its furthest western point: Spain.

In 711, Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed the straits (Gibraltar is literally named after him: Jabal Tariq). Within a few years, the Visigothic Kingdom had collapsed. But here’s what’s wild: the map usually stops at the Pyrenees because of the Battle of Tours in 732. Western history books love to say Charles Martel "saved" Europe, but most modern historians, like Hugh Kennedy, argue that the Umayyads were already at the end of their supply lines. They weren't looking to conquer France; they were on a raiding mission that got stopped because they were simply too far from home.

To the East, the expansion hit the borders of China. The Battle of Talas in 751 is one of the most underrated moments in history. It's the only time Arab and Chinese (Tang Dynasty) armies actually fought. The Arabs won, but they didn't push into China. Instead, something more important happened: according to legend, Chinese prisoners of war taught the Muslims how to make paper.

Paper changed the map more than swords ever did.

Once the Abbasids took over and moved the capital to Baghdad, the expansion wasn't about land anymore. It was about ideas. The "Green" on the map stayed relatively stable, but the influence of Islam started traveling via the Silk Road and the Indian Ocean trade routes.

Trade Routes: The Map's Invisible Growth

If you look at a map of Islam in the year 1200, you'll see large pockets of color in places the armies never went.

Indonesia. Malaysia. West Africa.

These areas weren't conquered. They were converted through commerce. Merchants from the Hadhramaut region of Yemen sailed to the Malay Archipelago. They brought spices back, and they brought Islam forward. In West Africa, the Mali Empire became a powerhouse not because of an invasion from the north, but because of the Trans-Saharan trade. When Mansa Musa made his famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, he brought so much gold that he literally crashed the economy of Cairo.

This is where the standard "conquest map" fails. It doesn't capture the cultural osmosis. You've got the Sufi orders traveling into Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, mixing local traditions with Islamic theology. It was syncretic. It was slow. It was deep.

Common Misconceptions About the Boundaries

- "It was all forced conversion": Honestly, the early Caliphates didn't even want everyone to convert right away. Non-Muslims paid the jizya tax, which was a huge source of revenue for the state. If everyone converted, the tax base shrank.

- "The map was a single empire": Only for a short time. By the 800s, the "Islamic world" was a collection of rival caliphates and sultanates—Abbasids in Baghdad, Fatimids in Egypt, and the Umayyads in Spain. They fought each other as much as they fought anyone else.

- "The expansion was just Middle Eastern": By the time the Ottoman Empire (the next big map-shifter) took Constantinople in 1453, the center of gravity had shifted to the Balkans and Anatolia.

The Ottoman and Mughal Layers

Later maps show the expansion into Eastern Europe and Northern India. The Mughal Empire under Akbar the Great represents a massive block of the map, but it was a unique kind of expansion. Akbar was famous for his religious pluralism, even trying to start a hybrid faith called Din-i Ilahi.

The Ottomans, meanwhile, pushed the map all the way to the gates of Vienna in 1683. This was the high-water mark. After this, the map begins to recede in some areas (like the Reconquista in Spain, which ended in 1492) and expand in others (like the spread into the Philippines and deep into Africa).

Why This History Matters for You Today

Understanding the map of the expansion of Islam isn't just an academic exercise. It explains why the modern world looks the way it does. It explains why Arabic is spoken in Morocco but not in Iran (who kept their Persian language). It explains the food, the architecture, and the legal systems across three continents.

If you’re traveling through Southern Spain (Andalusia), you’re walking on the map. You see it in the arches of the Mezquita in Cordoba. If you’re in Sicily, you see it in the agriculture and the names of towns. The map isn't just a relic; it's a blueprint.

How to Truly Learn This History

- Visit the Source Material: If you can, go to the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha or the British Museum. Seeing the actual coins and treaties from the 8th century makes the map feel real.

- Read the Nuance: Pick up The Venture of Islam by Marshall Hodgson. It's thick, but it's the gold standard for understanding how this civilization actually functioned.

- Follow the Trade: Don't just look at troop movements. Look at the "Incense Route" and the "Silk Road." The spread of Islam followed the money.

- Check the Language: Look at a linguistic map alongside the religious map. Where they overlap—and where they don't—tells you where the expansion was cultural versus where it was strictly political.

The map of the expansion of Islam is a living document. It shows us that borders are never as permanent as they look on paper, and that the most lasting "conquests" are usually the ones involving ideas, trade, and culture rather than just cavalry. To see the full picture, you have to look past the green ink and see the people moving underneath it.

Actionable Next Steps

To get a deeper, more accurate grasp of how these territories shifted over time, you should start by comparing a political map of the 8th century with a trade route map of the same era. You’ll notice that Islamic expansion almost perfectly mirrors the major commercial arteries of the medieval world. Next, look into the "Year of the Elephant" and the specific tribal dynamics of 7th-century Arabia to understand the social pressure cooker that started the movement. Finally, use an interactive historical atlas—like the ones provided by the Geacron project—to see the borders pulse year-by-year, which helps visualize just how fluid these "permanent" empires actually were.