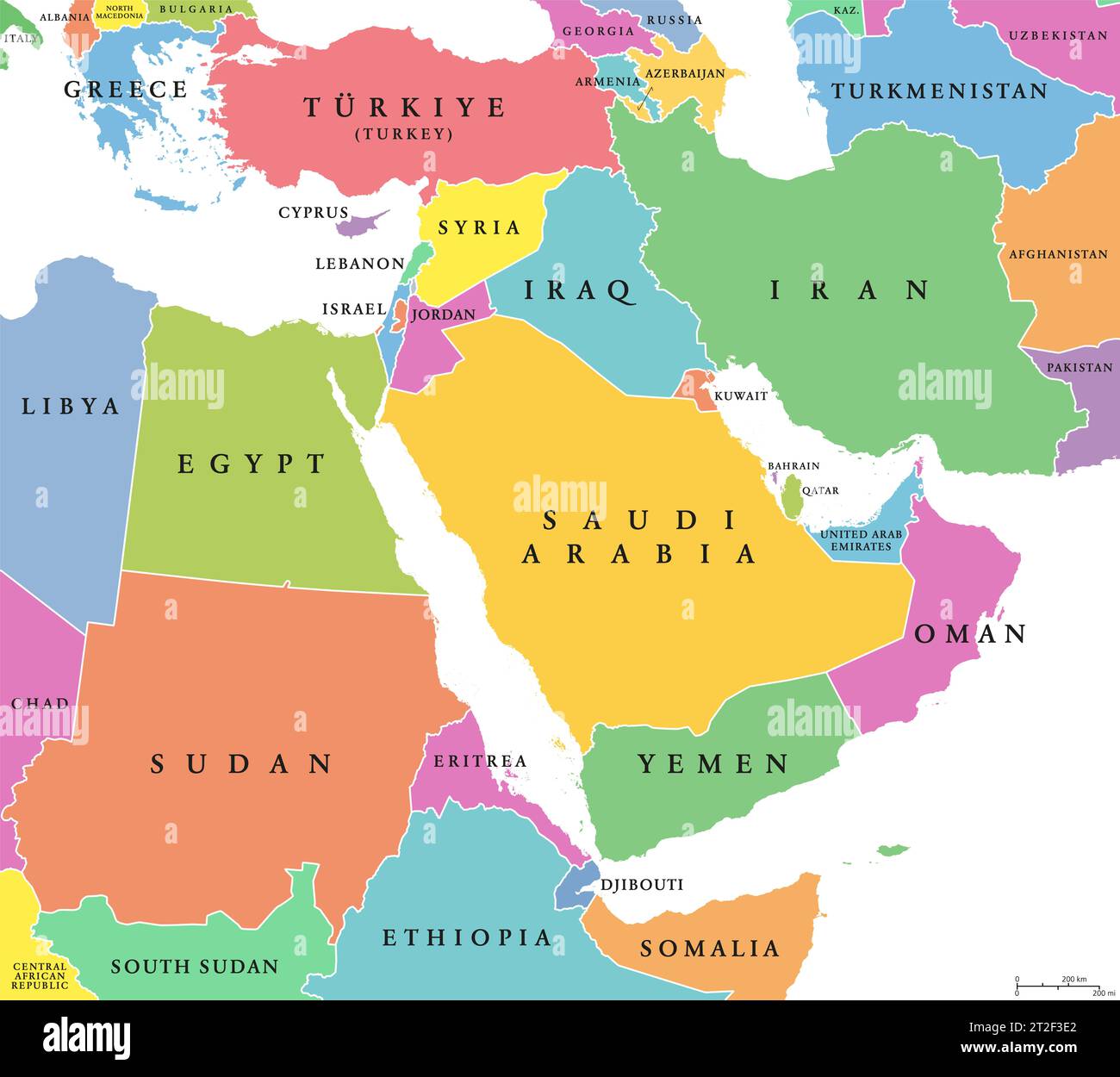

If you look at a map of the Middle East 1900, you won't see Iraq. You won't see Jordan, Lebanon, or Israel. Saudi Arabia? Forget it. It didn't exist yet. Instead, you see a massive, sprawling, slightly crumbling entity called the Ottoman Empire. It held the keys to the castle. But the map was a lie even then because the borders on paper didn't match the power on the ground.

It’s weird.

We're so used to these crisp, clean lines in the sand. But in 1900, the "Middle East" wasn't even a common term. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, an American naval strategist, only coined the phrase in 1902. Before that, folks just called it the Near East. If you were a traveler jumping on a steamship in Marseille heading for Beirut in 1900, you weren't "visiting the Middle East." You were entering the domains of Sultan Abdülhamid II.

The Ottoman Giant and Its Fragile Grip

The 1900 map is dominated by the color of the Ottoman Empire. From the peaks of the Taurus Mountains down to the humid marshes of Basra, it was all technically one country. But "technically" is doing a lot of heavy lifting here.

By 1900, the Empire was the "Sick Man of Europe." It was broke. It owed a mountain of debt to European banks. To pay for the telegraph lines and the fancy new Hejaz Railway—which reached Medina by 1908—the Sultan had to let foreigners basically run the tax office. Imagine a country where the IRS is managed by a committee of neighboring rivals. That was the reality.

In the Levant, places like Jerusalem and Damascus were thriving, cosmopolitan hubs. Jerusalem wasn't a divided city; it was an Ottoman mutasarrifate, a special administrative district reporting directly to Istanbul. People moved relatively freely. You could take a carriage from Jaffa to Jerusalem without showing a passport to three different militias.

📖 Related: How many miles is 1 000 km: The Reality of Crossing Borders and Unit Conversions

The maps of the time often show "Syria" as a massive province. But it wasn't the Syria we know. It was Bilad al-Sham. It included modern-day Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine. The borders were fluid. They followed mountain ranges and old Roman roads, not the geometric straight lines drawn by bored diplomats in 1916.

The British Presence in the Shadows

Look at the bottom of that 1900 map. You’ll see Egypt. On paper, Egypt was still part of the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan's face was on the coins. But honestly? The British were running the show. Since 1882, the British "Veiled Protectorate" meant that Lord Cromer—the British Consul-General—actually called the shots from Cairo.

They wanted the Suez Canal. It was the "jugular vein of the Empire," connecting London to India. If you were looking at a map in a London boardroom in 1900, Egypt was colored British red, regardless of what the official Ottoman maps claimed.

Then there's the Trucial States. That’s what we call the UAE now. Back then, they were just a collection of pearl-fishing villages and tribal lands that had signed "truces" with the British to stop piracy. Britain didn't want to rule the desert; they just wanted to make sure no other European power built a port on the way to India. It was about the water, not the sand.

Persia and the Great Game

Shift your eyes to the east. The Qajar Dynasty ruled Persia (modern Iran). In 1900, Persia was a giant chessboard. To the north, the Russian Empire was creeping down, hungry for a warm-water port. To the southeast, the British were pushing up from India.

The map of the Middle East 1900 shows Persia as an independent kingdom, but it was being squeezed like an orange. In 1901, just a year after our map's date, a guy named William Knox D'Arcy signed an oil concession with the Shah. This changed everything. Before oil, the Middle East was about transit—getting from Europe to Asia. After oil, the land itself became the prize.

Persian borders were messy. The frontier with the Ottomans in the Zagros Mountains was a nightmare of disputed valleys and nomadic tribes who didn't care about either Emperor. Tribes like the Bakhtiari or the Qashqai moved their herds based on the seasons, crossing "international borders" twice a year without a second thought.

The Interior: Land of No Maps

Most maps from 1900 leave the center of the Arabian Peninsula blank or label it "Rub' al Khali" (The Empty Quarter). It was the Wild West, but with camels.

In 1900, the House of Saud was in exile in Kuwait. They had lost their ancestral home of Riyadh to the Rashidi clan, who were backed by the Ottomans. The interior wasn't a "state." It was a shifting mosaic of tribal allegiances. If you were a cartographer in London or Paris, you just drew a big beige blob in the middle and called it a day.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Perfect Castle in the Snow: Why Some Look Better in Winter Than Others

Everything changed in 1902. A young Abdulaziz Ibn Saud led a daring night raid to recapture Riyadh. That single event, just two years after our 1900 snapshot, started the domino effect that led to the modern map. But in 1900? Saudi Arabia was just a dream in the head of a tall, ambitious man living in a tent in Kuwait.

What the 1900 Map Teaches Us Today

History isn't a straight line.

Looking at the map of the Middle East 1900 reminds us that the "ancient hatreds" people talk about are often much newer than we think. Many of the borders causing conflict today didn't exist 125 years ago. They were created by the Sykes-Picot Agreement during World War I, often ignoring the ethnic and religious realities that the Ottomans had managed (clumsily) for centuries.

The 1900 map is a portrait of a world on the brink.

It shows an era where empires were more important than nations. It shows a world before the car, before the airplane, and largely before oil. It shows a Middle East that was more connected to itself than it is now. You could ride a train from Istanbul to Medina. You could walk from Gaza to Cairo.

Why the Cartography Matters

Mapmaking in 1900 was a tool of empire. The French maps of North Africa and the British maps of the Persian Gulf weren't just for navigation. They were "claims." When a British surveyor mapped a well in the desert, he was planting a flag.

If you're researching this era, check out the RGS (Royal Geographical Society) archives. Their maps from 1900 are incredibly detailed but also incredibly biased. They focus on resources, telegraph lines, and coal stations. They often ignore the names of local villages in favor of the names of the tribes they needed to bribe.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you want to understand the modern Middle East, you have to start with the 1900 baseline. Here is how you can actually use this knowledge:

- Study the Railway Lines: Look at the path of the Hejaz Railway. It explains why certain cities in Jordan and Saudi Arabia grew while others faded. The infrastructure of 1900 dictated the urban planning of 2026.

- Trace the "Vilayets": Instead of looking for modern countries, look for Ottoman Vilayets (provinces). The Vilayet of Basra, the Vilayet of Baghdad, and the Vilayet of Mosul were lumped together to create Iraq in 1920. Knowing they were separate in 1900 explains a lot of the internal friction in Iraq today.

- Look at the Ports: In 1900, cities like Smyrna (Izmir), Beirut, and Alexandria were more similar to each other than they were to their own inland capitals. They were Mediterranean hubs.

- Check the 1901 Oil Concession: Research the D'Arcy Concession. It is the "patient zero" for the modern geopolitical obsession with the region.

- Acknowledge the Nomadic Factor: Remember that 1900 was a time when a significant portion of the population was migratory. Maps represent "sedentary" power, but the real power often moved with the seasons.

The 1900 map isn't just a piece of paper. It's a ghost. You can still see its outlines in the news every night, in the contested borders of the Levant, and in the enduring influence of the old imperial capitals. To understand where the region is going, you have to see where it was when the lines were still being drawn in pencil, before they were carved in stone and blood.