Nathaniel Hawthorne was tired. By 1858, the man who gave us the heavy, brooding guilt of The Scarlet Letter had spent years as a bored bureaucrat in Liverpool. He needed a change. He moved his family to Italy, and honestly, it changed everything. While wandering through the Palazzo Nuovo in Rome, he stopped dead in front of a statue—the Faun of Praxiteles.

That block of stone sparked something.

✨ Don't miss: Negligence: Why the Cast of This Thriller Is Getting Everyone Talking

It became The Marble Faun, Hawthorne’s final completed novel and easily his most "vibey" work. Published in 1860, it’s a weird, beautiful, and sometimes frustrating mix of a travel guide, a Gothic murder mystery, and a deep psychological dive into what happens when a "perfect" person commits a terrible crime.

If you’ve ever felt like your past is a ghost following you through a crowded room, you'll get this book.

The Story Most People Get Wrong

A lot of people think The Marble Faun is just about a statue. It’s not. It’s about four friends living the "expat life" in 19th-century Rome. You’ve got Kenyon, a sculptor who’s a bit too rational for his own good. Then there’s Hilda, a New England "dove" who spends her days copying Old Masters and being annoyingly innocent.

Then it gets interesting.

Miriam is a painter with a "shadow" in her past. We never quite learn her whole deal—is she a disgraced noble? A Jewish heiress? Hawthorne keeps it blurry. Finally, there’s Donatello. He’s a young Italian count who looks exactly like that marble faun statue. He’s happy, simple, and basically an animal in human clothes.

Everything goes sideways during a moonlit walk at the Tarpeian Rock.

A mysterious man—Miriam’s "Model" or stalker—shows up. In a split second of passion, Donatello looks at Miriam, sees her silent plea for help, and hurls the guy off the cliff. Dead.

Just like that, the "Faun" isn't a playful creature anymore. He’s a murderer.

Why The Marble Faun is Actually About "The Fall"

Hawthorne was obsessed with the idea of the felix culpa, or the "fortunate fall." Basically, it’s the theory that Adam and Eve eating the apple was actually a good thing because it made humans "real."

Donatello starts the book as a beautiful, shallow kid. He’s "innocent" because he doesn’t understand pain. Once he kills that man, his soul wakes up. It’s heavy stuff. He loses his joy, sure, but he gains a conscience. He becomes a man.

The Contrast of Characters

- Miriam: She’s the catalyst. She carries the guilt of the Old World—dark, complicated, and tragic.

- Hilda: She’s the "New World" response. When she sees the murder, she falls apart. She can’t handle the "gray area" of morality. She even ends up confessing to a Catholic priest just to get the weight off her chest, which was a huge deal for a Puritan girl to do back then.

- Kenyon: He represents the artist’s struggle. He tries to shape reality into marble, but he realizes life is way messier than a sculpture.

Rome as a Living Graveyard

One thing you’ll notice if you actually sit down to read it is that Hawthorne spends a lot of time talking about ruins. He kind of treats Rome like a giant, beautiful corpse.

He calls it a "heap of renovating ruins."

💡 You might also like: Why Temperature by Sean Paul Still Runs the Dancehall Game Two Decades Later

For Hawthorne, Italy was the "Old World"—full of blood, history, and secrets. He contrasts this with the "New World" (America), which he saw as thin and lacking depth. It’s funny because, today, we think of the 1850s as "ancient history," but to Hawthorne, he was the modern guy looking back at a civilization that had already died ten times over.

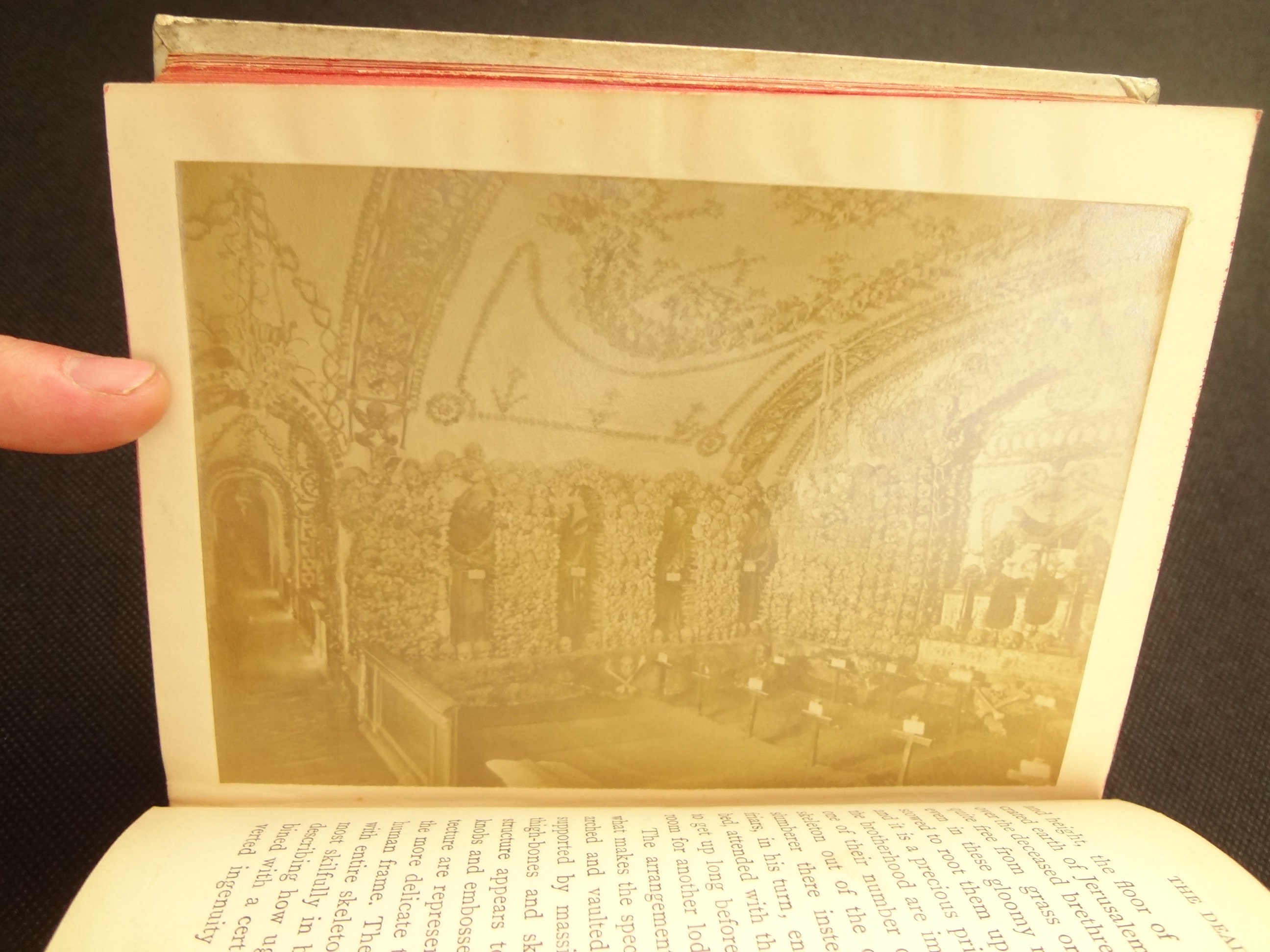

The book actually functioned as a travelogue for Victorian tourists. People would literally carry copies of The Marble Faun around Rome like a Lonely Planet guide. They wanted to see the exact spots where Miriam and Donatello walked.

The Ending That Made Everyone Mad

When the book first came out, readers hated the ending.

Why? Because Hawthorne didn't wrap it up. He left Miriam’s past a mystery. He didn't say if Donatello went to prison forever or if he found peace. People were so annoyed that Hawthorne actually had to write a "Postscript" for the second edition to explain things.

Even then, he basically told the readers: "If you didn't get it, you weren't paying attention."

He wanted the story to feel like a dream—or a "moonshiny romance," as he called it. Real life doesn't always have a neat ending where the bad guy goes to jail and the good guys get married and live happily ever after. Sometimes, you just walk away with a heavier heart and a bit more wisdom.

How to Approach The Marble Faun Today

If you’re going to read it, don't rush. It’s a slow burn.

The language is thick. It’s clotted with descriptions of incense, marble, and Italian sunshine. But if you look past the 19th-century fluff, you’ll find a story that’s surprisingly modern. It’s about the "burden of seeing." Once you see something terrible, you can’t "un-see" it. You can't go back to being the person you were before.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Students

- Look at the Art: If you’re reading this for a class, Google the Faun of Praxiteles and Guido Reni’s Beatrice Cenci. Hawthorne uses these specific artworks as symbols for the characters’ inner lives.

- Track the "Shadow": Notice how the word "shadow" or "gloom" appears. It’s Hawthorne’s favorite way to signal that a character is losing their innocence.

- Don't skip the "London" edition: If you find a copy titled Transformation, don't be confused. That was the British title, and Hawthorne actually hated it. He thought it gave away the plot too much.

- Compare the Women: Watch how Miriam (the "dark" woman) and Hilda (the "light" woman) react to the same crime. It says a lot about how Victorian society viewed "purity" versus "experience."

The Marble Faun isn't just a relic of 1860. It’s a reminder that being "human" means being flawed. We all fall. The question Hawthorne asks isn't "how do we stay innocent?" but "what do we do once the innocence is gone?"

Go find a copy. Read it near a window with good light. Let the Roman atmosphere soak in. You might find that your own "marble" starts to feel a bit more like flesh and blood.

Next Steps

To get the most out of Hawthorne's work, try comparing the themes of guilt in The Marble Faun with his earlier short story Young Goodman Brown. You'll see the same "loss of innocence" theme, but set in the dark woods of Salem instead of the sun-drenched ruins of Rome. This comparison makes it much easier to understand how his time in Italy shifted his perspective from "sin is a trap" to "sin might be a teacher."