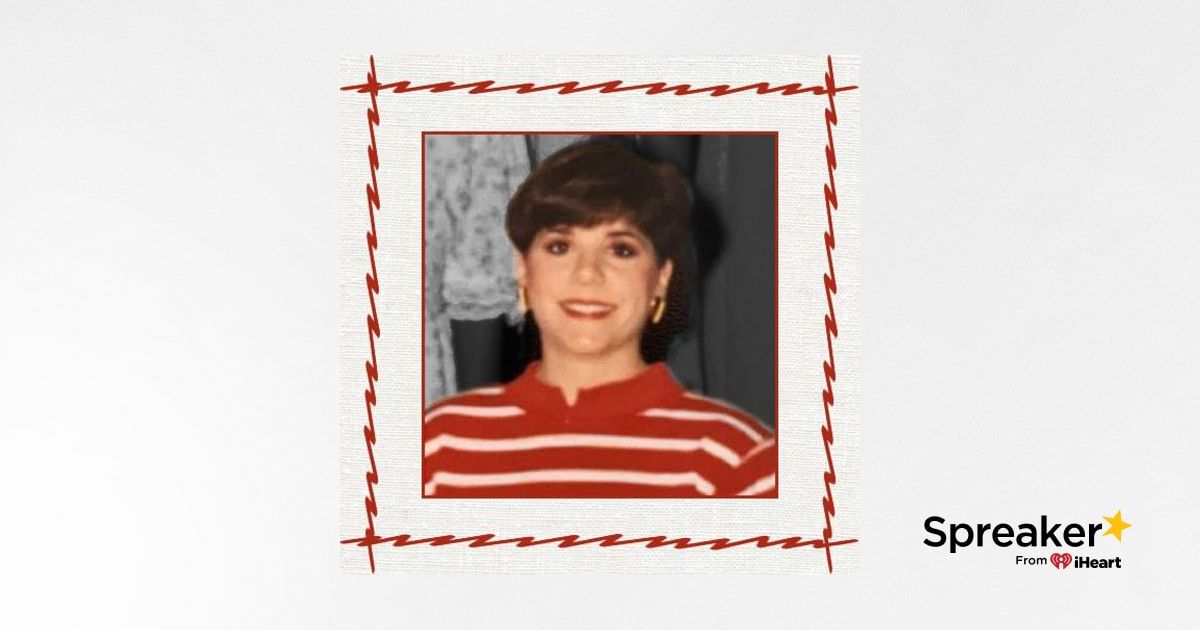

Texas summers are heavy. But the heat in Beaumont on January 14, 1995, felt different for the friends and family of Mary Catherine Edwards. She was a 31-year-old schoolteacher, well-loved, the kind of person who didn't just show up for her students at Price Elementary—she lived for them. When she didn't answer her door that Saturday, her parents went to check on her. What they found changed the city forever.

Mary Catherine had been raped and murdered. The scene was brutal. It was the kind of crime that leaves a permanent stain on a community’s sense of safety. For decades, the Mary Catherine Edwards murder was the ghost that haunted the Beaumont Police Department. Leads went nowhere. Sketches gathered dust. DNA technology just wasn't where it needed to be.

Then came the shift. It took twenty-six years, but the breakthrough didn't come from a sudden confession or a new witness. It came from a spit tube and a family tree.

💡 You might also like: Los Angeles Fire Live: What Most People Get Wrong About Tracking Wildfires

Why the Mary Catherine Edwards murder went cold for decades

Back in '95, the tools were primitive. Police had DNA, sure, but the national databases like CODIS only worked if the killer was already in the system for another violent crime. If the guy kept his nose clean or just didn't get caught for anything else, he was a ghost.

The investigation was massive. Beaumont detectives interviewed hundreds of people. They looked at colleagues, ex-boyfriends, and local creeps. Nothing stuck. You have to imagine the frustration of having the killer's literal biological signature—his DNA—and having absolutely no name to attach to it. It’s like having a key but no idea where the door is located.

People in Beaumont started to think the killer had hopped on I-10 and vanished into another state. Maybe he was dead. Maybe he was in prison under a different name. The case sat in a filing cabinet, a thick stack of "what-ifs" and dead ends.

The turning point in forensic science

Everything changed because of what we now call Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG). You've probably heard of it through the Golden State Killer case. Basically, investigators take the crime scene DNA and upload it to public databases like GEDmatch or FamilyTreeDNA—places where regular people go to find their long-lost Irish cousins.

In 2020, the Beaumont Police Department and the Texas Rangers teamed up with the FBI. They weren't looking for a direct match anymore. They were looking for the killer’s third cousin. Or his great-aunt.

By mapping out these distant relatives, genealogists build "reverse" family trees. They find a common ancestor from the 1800s and then work their way down to the present day until they find a male relative who was in the right place at the right time. In the Mary Catherine Edwards murder, that tree pointed directly to a man named Clayton Foreman.

Who is Clayton Foreman?

Clayton Bernard Foreman wasn't a stranger. That’s the part that really stings.

Foreman had attended Forest Park High School with Mary Catherine. He was a year behind her. He even lived in the same neighborhood at one point. This wasn't some random drifter passing through town. This was someone who likely knew her face, maybe even her routine.

When police started digging into Foreman’s past after the DNA link surfaced, they found a chilling pattern. In 1981, over a decade before Mary Catherine was killed, Foreman had been arrested for a strikingly similar attack. He had tied up a woman and assaulted her, claiming he was a police officer. He took a plea deal back then—a slap on the wrist, honestly—and served three years of probation.

👉 See also: No Kings Protest: What People Are Actually Fighting For in 2026

He moved to Ohio. He started a family. He lived a quiet, suburban life for nearly thirty years while the Edwards family lived in a state of perpetual grief.

The arrest in Reynoldsburg

In April 2021, detectives traveled to Reynoldsburg, Ohio. They didn't just knock on his door and ask for a sample. They followed him. They waited for him to discard something with his DNA on it.

Once they grabbed his trash, the lab confirmed it: the DNA from the 1995 crime scene was a 1-in-a-billion match to Clayton Foreman.

Imagine being his neighbors. You see this guy every day, maybe you've had a beer with him or seen him mowing his lawn, and then the FBI rolls up because he allegedly strangled a teacher in Texas during the Clinton administration. It's surreal. It’s the kind of thing that makes you look at everyone on your block a little differently.

The legal battle and the eventual plea

The wheels of justice turn slowly, especially when you're dealing with a case this old. Foreman was extradited back to Jefferson County, Texas. There was a lot of back-and-forth. Legal maneuvers. The usual stuff that happens when a defense team tries to pick apart decades-old evidence.

However, the DNA evidence was essentially an iron wall. You can't argue with biology.

In 2024, Clayton Foreman finally faced the music. He pleaded guilty to the murder of Mary Catherine Edwards. He was sentenced to life in prison. He was 63 years old at the time of the plea. While it doesn't bring Mary Catherine back, it does ensure that Foreman will likely die behind bars, stripped of the "normal" life he enjoyed for the twenty-six years he evaded capture.

💡 You might also like: List of Presidents and Political Party Explained (Simply)

Why this case matters for cold cases everywhere

The Mary Catherine Edwards murder isn't just a local Texas story. It’s a blueprint.

There are thousands of "Mary Catherines" sitting in police files across the country. For a long time, we thought those cases were unsolvable because the "trail went cold." But genetic genealogy has proven that the trail never actually goes cold—it just goes microscopic.

- Public Databases: The success of these cases depends on people opting into law enforcement matching on sites like GEDmatch.

- Funding: These investigations are expensive. They require specialized genealogists and high-end lab work.

- Privacy Debates: There's always a conversation about whether police should have access to this data, but in cases of rape and murder, the public tide has mostly turned toward "catch the monster."

What we can learn from Mary Catherine's legacy

Mary Catherine Edwards was more than a victim. She was a teacher who left an impact on hundreds of kids in Beaumont. When you talk to her former students now—adults in their 40s—they remember her classroom as a safe place.

The resolution of this case reminds us that time isn't a shield for criminals. It also highlights the agonizing patience required by families. Her parents didn't live to see the arrest; they passed away before the DNA technology caught up to their daughter's killer. That is the tragic reality of many cold cases. Justice arrives, but sometimes it arrives at an empty house.

If you’re following these types of cases, the takeaway is clear: the science is winning.

Actionable insights for those following cold cases

If you are interested in supporting the resolution of cold cases like the Mary Catherine Edwards murder, there are actual things you can do besides just listening to true crime podcasts.

Upload your DNA results. If you’ve done a kit through Ancestry or 23andMe, you can download your raw data and upload it to GEDmatch. Make sure you "opt-in" to law enforcement searches. You might be the distant cousin who helps identify a killer or identifies "Jane Doe" remains.

Support Cold Case Units. Many police departments don't have the budget for genetic genealogy. Organizations like Season of Justice provide grants to help fund the testing needed for these breakthroughs.

Keep the names alive. Public interest often drives funding. When people keep talking about unsolved cases, it puts pressure on local governments to allocate resources to their cold case squads.

The closure in Beaumont proves that no matter how much time passes, the truth has a way of surfacing. Clayton Foreman thought he got away with it. He had every reason to believe he was safe. He was wrong.

Next Steps for Further Reading:

- Research the "Texas Rangers Unsolved Crimes Investigation Program" to see other active cases in the region.

- Look into the "Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) National Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI)" which funds the testing of backlogged kits that often lead to these types of breaks.