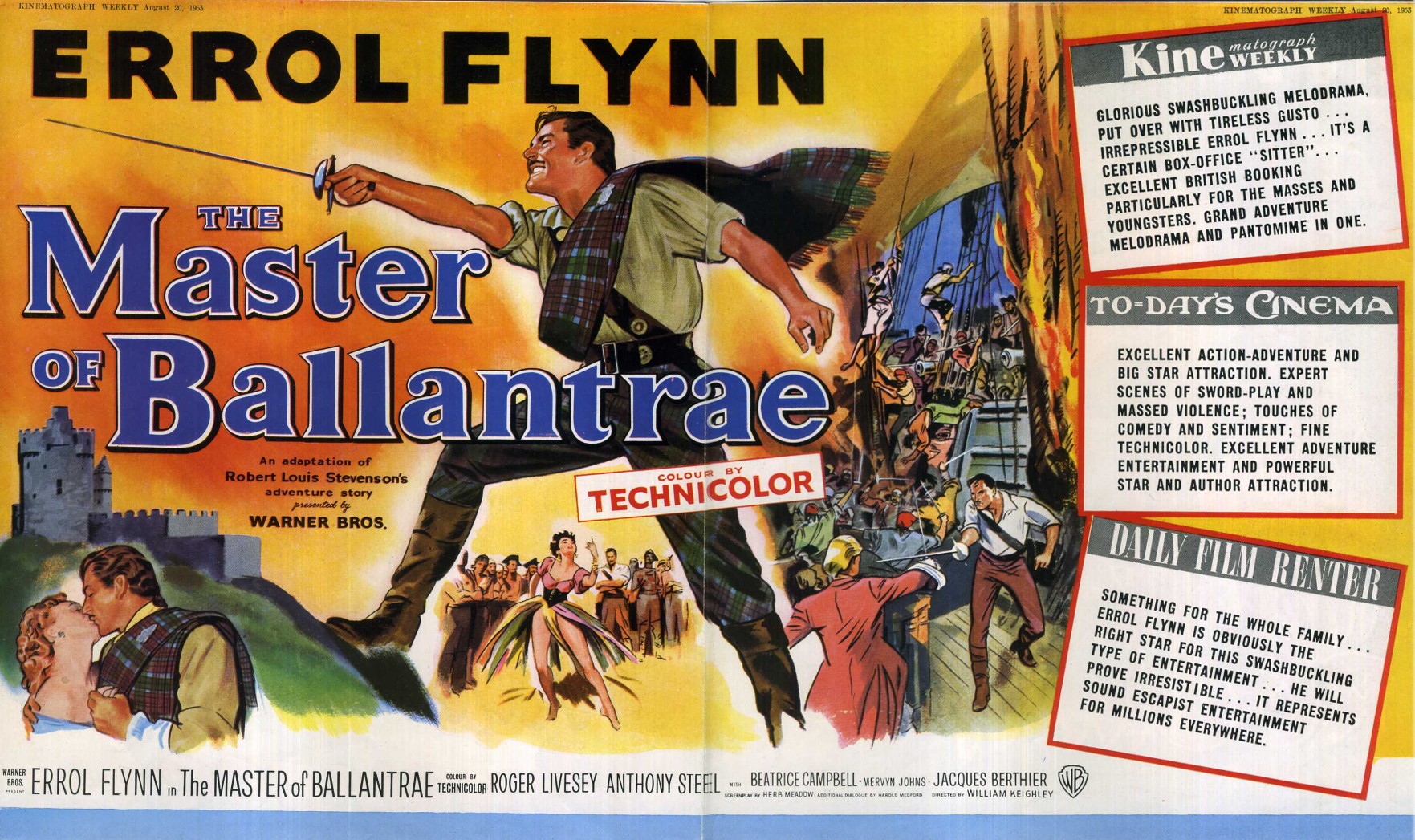

Errol Flynn was tired. By 1953, the man who had defined the cinematic hero of the 1930s—the guy who literally was Robin Hood—felt his age catching up with him. He was 44, his lifestyle was legendary for all the wrong reasons, and the Hollywood studio system was shifting under his feet. Yet, in the middle of this career twilight, we got The Master of Ballantrae film. It’s a strange, salty, and surprisingly gritty piece of cinema that doesn't get enough credit for how it handled Robert Louis Stevenson’s notoriously difficult source material.

Most people remember the book. It’s a dark, psychological slog through sibling rivalry and the Jacobite rising of 1745. But the movie? It’s something else entirely. It’s a Technicolor explosion that tries to balance Stevenson's gloom with the "Flynn magic" people paid to see.

What actually happened during production

Warner Bros. didn't just stay on a backlot for this one. They went to Scotland. Honestly, you can feel the dampness in the frames. Shooting at Eilean Donan Castle gave the film a texture that many of Flynn's earlier, stage-bound adventures lacked. It wasn't just Scotland, though; they hauled the crew to Palermo, Sicily, to stand in for the more tropical locales.

Director William Keighley was at the helm. This was his last film. He’d worked with Flynn before on The Adventures of Robin Hood, so he knew how to manage the star's eccentricities and his waning stamina. There’s a persistent rumor that Flynn was "phoning it in," but if you watch his swordplay in the duel scenes, particularly the one against Anthony Steel (playing his brother Henry), the old spark is clearly there. He might have been leaning on his stunt double more than in 1938, but the charisma is undeniable.

The plot deviates from the book. Heavily. If you’re a Stevenson purist, you’re gonna have a bad time. The novel ends in a bleak, almost supernatural burial scene in the American wilderness. The 1953 Master of Ballantrae film opts for a more traditional adventure ending. It’s basically a pirate movie in the middle and a highland drama at the ends. It’s messy. It’s fun. It’s very much a product of its era.

The cast that held it together

Roger Livesey. That’s the name you need to remember. He plays Colonel Francis Burke, the Irishman who tags along with Jamie Durie (Flynn). Livesey brings a gravitas and a gravelly voice that anchors the film when Flynn starts to drift into his usual charming antics. He was a powerhouse of the British stage and screen, and his presence makes the film feel more like a "real movie" and less like a generic adventure flick.

Then you have Beatrice Campbell. She plays Lady Helen. In many ways, her role is the standard "waiting woman" trope of the 50s, but she manages to convey the genuine tragedy of the Durie family feud. The conflict between the two brothers—Jamie, the reckless rebel, and Henry, the "loyal" brother who stays behind—is the engine of the story. In the book, Henry is a sympathetic, crumbling character. In the film, he’s a bit more of a foil for Jamie’s heroics.

British cinema stalwarts like Mervyn Johns and Felix Aylmer pop up too. The casting reflects a transition period where Hollywood was heavily utilizing British talent to save on production costs through the Eady Levy. This gave the film a hybrid feel: American pacing with a distinctly British soul.

💡 You might also like: Why Leave it to Beaver on DVD Still Wins Over Streaming

Why the Master of Ballantrae film matters now

We live in an age of gritty reboots. Everything is dark, desaturated, and "realistic." Looking back at this 1953 version is a reminder of when "scope" meant something different. The Technicolor palette, supervised by cinematographer Jack Cardiff (though he isn't the primary credited DP, his influence on the era's look is everywhere), makes the Scottish highlands look like a dreamscape.

Critics at the time were lukewarm. They thought Flynn was too old. They thought the script was too light. But they missed the point. This was a transition movie. It represents the end of the "Golden Age" swashbuckler. After this, the genre started to fade, replaced by the more cynical Westerns and the rise of television.

It's also worth noting the music. William Alwyn’s score is sweeping. It doesn’t just underline the action; it drives it. It’s the kind of orchestral bravado that modern films often shy away from in favor of ambient drones.

Comparing the 1953 version to other adaptations

There have been other attempts to bring this story to the screen.

- The 1984 TV movie with Richard Thomas and John Gielgud.

- Various BBC miniseries.

None of them have the sheer scale of the 1953 production. While the 1984 version is arguably more faithful to the book's psychological horror, it lacks the "movie star" energy that Flynn brings. You can't replace that. Even a tired Errol Flynn is more watchable than most actors at their peak.

The technical hurdles of 1953

Shooting on location in the 50s wasn't the "run and gun" style we see today. They were lugging massive Technicolor cameras—huge three-strip beasts—across the Scottish heather. This limited how much they could actually move the camera. If you watch closely, you'll see a lot of static shots during the outdoor sequences. The movement comes from the actors, not the lens.

This technical limitation actually helps the film’s atmosphere. It feels stately. It feels like a historical epic should feel. When the action does kick in, the contrast is sharper. The duel on the cliffs is a masterclass in using geography to build tension.

Where the film goes wrong (And why it’s okay)

The middle act is basically a different movie. Jamie joins pirates. Why? Because it’s an Errol Flynn movie and people wanted to see him on a ship. This "pirate interlude" is almost entirely disconnected from the Jacobite politics of the first act. It’s a detour. A long one.

Does it hurt the pacing? Yeah, kinda. But it also gives us some of the best visuals in the film. The ship-to-ship combat is well-choreographed and reminds you why Warner Bros. was the king of the high seas in the 40s.

The film also glosses over the "evil" of the Master. In Stevenson’s book, Jamie is a sociopath. He’s a charming, terrifying monster who ruins everyone he touches. In the movie, he’s more of a misunderstood rogue. This softens the story's blow, but it makes it more palatable for a Saturday afternoon audience in 1953. It’s a trade-off. You lose the literary depth, but you gain a hero you can actually root for.

Actionable insights for fans and collectors

If you're looking to dive into the Master of Ballantrae film, don't just settle for a random streaming rip. The restoration work done on the DVD and Blu-ray releases is significant. The Technicolor needs that high bitrate to really pop.

- Watch for the costumes: Margaret Furse, an Oscar winner, did the costumes. The attention to 18th-century detail in the Highland wear is surprisingly accurate for a Hollywood production of this era.

- Listen to the score: Find the isolated score if you can. William Alwyn’s work here is a textbook example of how to use leitmotifs for character development.

- Compare the ending: Read the last three chapters of the Stevenson novel after watching the movie. The difference in tone is staggering and will give you a great appreciation for how much the "Studio System" filtered literature for the masses.

- Check out the locations: If you’re ever in Scotland, Eilean Donan Castle is the primary spot. Seeing it in person makes you realize how much work went into getting those 1950s crews up there.

This film is a time capsule. It’s the sound of a genre taking its final bow before the world changed. It’s Errol Flynn saying goodbye to the sword, and it’s a gorgeous, flawed, and entertaining piece of cinema history that deserves a spot on your "to-watch" list.

For the best experience, track down the Warner Archive Collection release. It preserves the original aspect ratio and handles the color timing much better than the older television broadcasts. Seeing those Highland greens against the red of the British tunics in high definition is exactly how the film was meant to be experienced.

Don't go in expecting a deep psychological thriller. Go in for the spectacle. Go in to see a legend one last time. It’s not a perfect movie, but it is a perfectly enjoyable one.