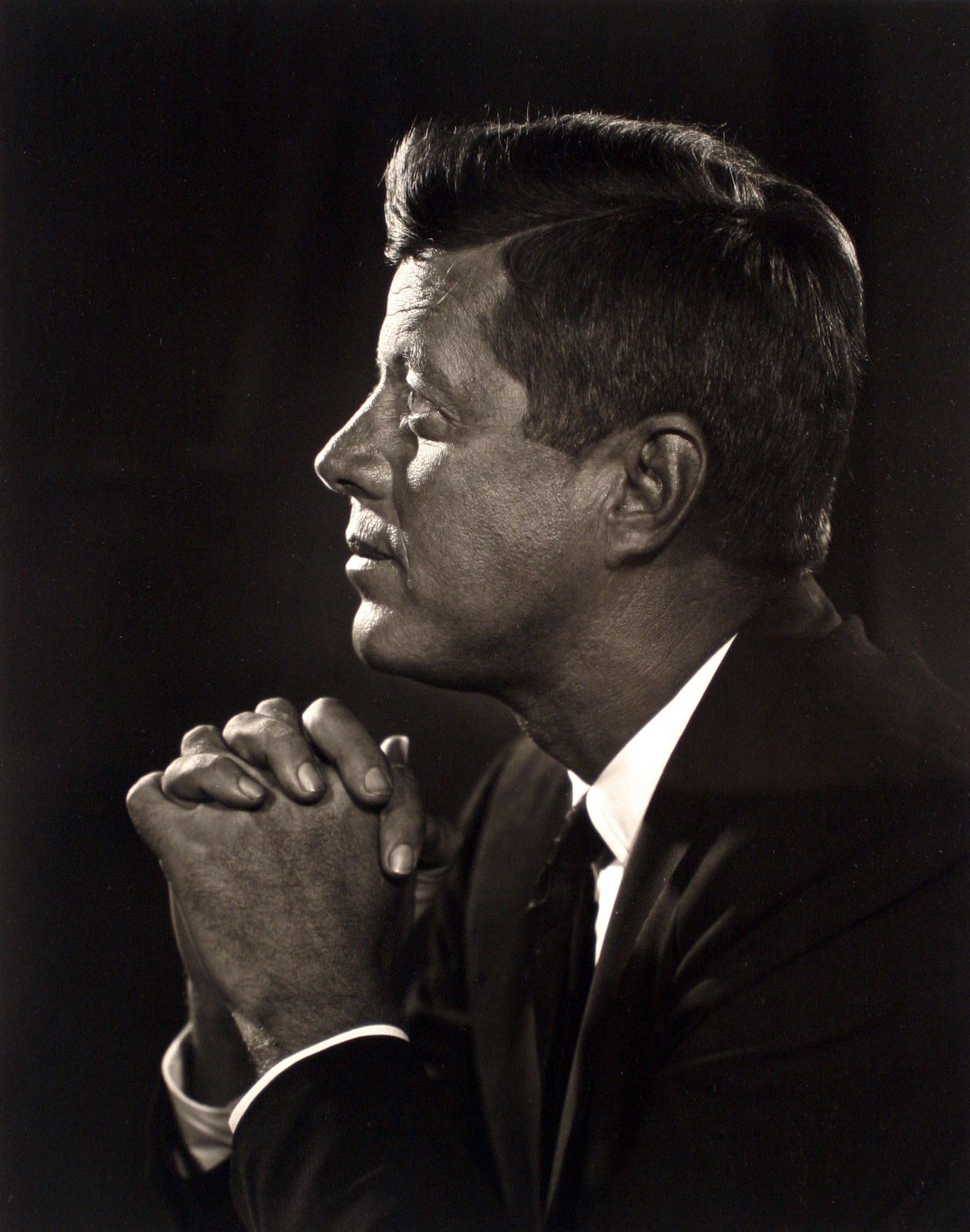

Walk through the Grand Foyer of the White House and you’ll see them. Rows of men—mostly—staring you down with iron-jawed confidence. They sit at desks. They stand by globes. They look like they’re ready to sign a treaty or command an army. Then, you hit the Cross Hall. You stop.

There stands Jack. But he isn’t looking at you.

The official portrait of JFK is arguably the most recognizable piece of art in the Executive Mansion, yet it remains the most controversial. Painted by Aaron Shikler in 1970, seven years after the shots rang out in Dealey Plaza, it depicts John F. Kennedy with his head bowed and arms tightly crossed. It’s quiet. It’s heavy. Honestly, it feels less like a state portrait and more like a private moment of grief caught on canvas.

A Widow’s Vision: Breaking the Mold

Most people assume the somber tone was Shikler’s idea—a tribute to a fallen leader. That’s only half the truth. The real driving force was Jacqueline Kennedy.

Jackie was over the "Camelot" gloss. She was tired of the images that made her husband look like a "postage stamp" hero with a penetrating gaze and perfectly airbrushed skin. She specifically told Shikler she didn't want the bags under his eyes hidden or his face made to look like a statue. She wanted the man.

Basically, she wanted a "thinking" president.

Shikler struggled at first. How do you paint the most photographed man in the world without falling into the trap of a cliché? He flipped through hundreds of photos. He looked at sketches. He finally found his "lightbulb" moment in a photo of the President’s brother, Ted Kennedy. In the photo, Ted was standing at JFK’s grave, head down, arms crossed in that signature Kennedy stance.

Shikler adapted that pose for the President. When Jackie saw the sketch, she chose it immediately over several more traditional options. She knew it was the one.

📖 Related: Mia Khalifa Is Dead: What Really Happened With the Rumors

The Mystery of the Eyes

There is a persistent rumor that Shikler painted the eyes downcast because he didn't want to "paint the eyes of a dead man."

It’s a haunting thought. But Shikler himself was a bit more pragmatic about it. He felt that by hiding the eyes, he was showing a leader who was a "metaphor of America at a crossroads." He wanted to show a man burdened by the weight of the world—the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Cold War, the Civil Rights movement.

If you look closely at the brushwork, it’s not just about the pose. The colors are muted. There’s a certain haziness to the edges. It’s a "character study," as art historians call it. Most presidential portraits are about power. This one is about the internal life of a human being.

The Critics Had a Field Day

Not everyone loved the "Thinking President." When the portrait was finally unveiled in February 1971, critics were harsh. Some thought it was too depressing. They argued that an official portrait should project strength and vitality, not introspection and sorrow.

Others complained it looked "unfinished" or "ghostly."

But Jackie stood her ground. She returned to the White House for the first and only time after leaving in 1963 just to see the portraits (Shikler also painted hers, which is equally ethereal). She brought Caroline and John Jr. with her. They stood in the East Room, away from the cameras, and looked at their father.

For the Kennedy family, it wasn't a painting of a martyr. It was a painting of a husband and a father who used to stand in that very room, lost in thought, figuring out how to keep the world from blowing up.

Why the Official Portrait of JFK Still Matters

In a world of high-definition selfies and curated political images, Shikler’s work stands out because it’s so raw. It breaks the rules of political branding.

- It’s Posthumous: Unlike most presidents who sit for their portraits, Kennedy’s was a reconstruction of memory and photography.

- The Pose: No other president is depicted looking down. It’s the only one that breaks "eye contact" with the viewer.

- The Location: It hangs in the Cross Hall, a high-traffic area where its vulnerability contrasts sharply with the formality of the architecture.

Comparing the "Rejected" Portraits

Shikler wasn't the only one who tried to capture the 35th President. Jamie Wyeth painted a famous portrait of JFK where he's leaning on a hand, looking slightly distressed. Robert Kennedy actually rejected that one because he thought it made his brother look too "uncertain" during the Bay of Pigs.

Then there was Gardner Cox, who actually had Kennedy sit for him while he was alive. That painting was never finished because of the assassination, and the version Cox eventually turned in was rejected by Jackie for being too stiff.

Shikler’s version won because it captured the vibe of the era—the mixture of high hope and deep tragedy.

How to See It for Yourself

If you want to see the official portrait of JFK, you’ve gotta go to the source. It’s part of the White House Collection and is usually on view during public tours.

- Book early: White House tours need to be requested through your Member of Congress up to three months in advance.

- Look for the Cross Hall: That's its usual home on the State Floor.

- Check out the First Lady’s portrait too: Jackie’s portrait is nearby. It’s done in peach and mauve tones and has the same "ghostly" quality that Shikler favored.

- Visit the Smithsonian: If you can't get into the White House, the National Portrait Gallery has a different, equally famous portrait of Kennedy by Elaine de Kooning. It’s much more abstract and green, but it captures his energy in a totally different way.

The painting isn't just a record of what he looked like; it's a record of how we choose to remember him. It's a reminder that leadership isn't just about the public speech—it's about the quiet, heavy moments that happen when the cameras are off.