It happened in the middle of a May night in 2003. While the rest of the White Mountains slept under a thick blanket of spring mist, 7,000 tons of granite just... gave up. By the time the sun hit Franconia Notch the next morning, the most famous face in America was gone. It wasn’t a slow erosion. It was a collapse. People showed up to the viewing lake, looked up at Cannon Mountain, and rubbed their eyes because they thought the fog was playing tricks on them. But the Old Man of the Mountain wasn't there anymore.

If you aren't from New England, it’s hard to explain why people were literally weeping on the side of the I-93 highway that week. It was just a rock, right? Well, not really. To folks in New Hampshire, it was a biological relative. It’s on the state quarter, the road signs, and the license plates. It’s the identity of the place. Even now, decades after the fall, we’re still talking about it like it’s a recent tragedy.

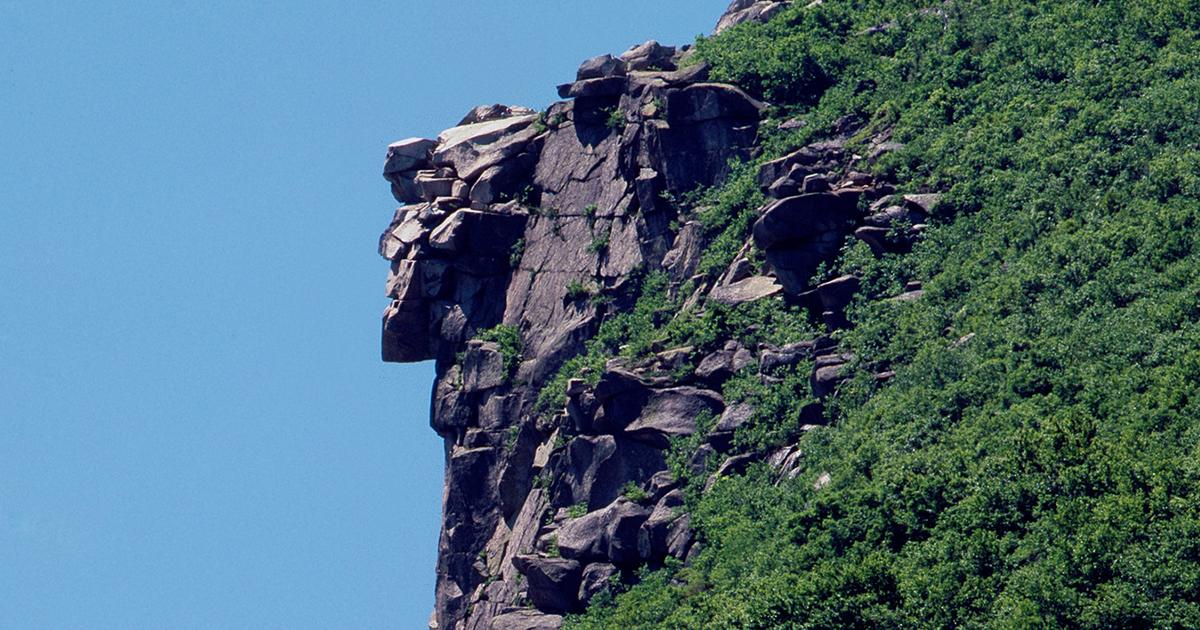

Geologically, the profile was a freak of nature. Five separate granite ledges aligned perfectly—if you stood at exactly the right spot—to create the image of a stern, craggy face looking out toward the East. If you moved ten feet to the left? Just a pile of rocks. But from that one specific vantage point, it was unmistakable. It looked alive.

The Long Fight Against Gravity

Nature didn't want the Old Man to stay up there. Let's be real: hanging thousands of tons of rock off a cliff face using nothing but friction and luck is a bad long-term strategy. The profile was formed by the retreat of glaciers about 12,000 years ago. Ever since then, water had been getting into the cracks.

👉 See also: LA to Vegas Travel Time: Why Google Maps Is Usually Lying to You

New Hampshire winters are brutal. Water gets in, freezes, expands, and pushes the rock apart. This is "frost wedging," and it’s been trying to kill the Old Man since the day he was born. By the 1920s, the "forehead" of the profile had a crack so wide you could almost jump across it.

Enter the Keepers of the Face

Edward Sayre was the first one to really try and "fix" the mountain in 1916. He used turnbuckles and steel rods to tie the forehead to the main cliff. It was a desperate move. Later, the task fell to Niels Nielsen, a state highway worker who became the official "keeper" of the profile. He spent decades climbing up there, often in dangerous winds, to patch cracks with epoxy and sealants.

Niels’ son, David Nielsen, eventually took over. It was a family business of the strangest kind. They weren't just surveyors; they were surgeons for a mountain. They’d lug heavy equipment up the back side of Cannon Mountain, rappelling over the edge to make sure the face didn't slide into the notch. Honestly, it’s a miracle it lasted as long as it did with just some steel cables and some 1950s-era "waterproofing" holding it together.

What Actually Happened That Night?

People love a good conspiracy, but the truth is pretty boring. There wasn't an earthquake. No one used dynamite. It was just gravity and a lot of rain. The week leading up to May 3, 2003, was incredibly wet. The weight of the water combined with the existing stress on the turnbuckles finally reached a breaking point.

The center of gravity shifted. Once that main "chin" block went, the whole thing unzipped.

💡 You might also like: Why the Raffles Hotel Singapore Singapore Sling is still the drink you have to try at least once

When the park rangers realized he was gone, the news hit the wire like a political assassination. The governor at the time, Craig Benson, actually floated the idea of rebuilding it. He wanted to use fiberglass or synthetic rocks to put the face back. People hated that idea. New Hampshirites are a stubborn bunch, and the general consensus was: if Nature took him down, let him stay down. There's something weirdly disrespectful about a plastic mountain, you know?

Visiting the Site Today: Is It Worth It?

You can still go to Franconia Notch State Park. In fact, you should. But don't expect to see a face on the cliff. If you look up now, you’ll see a jagged "scar" where the granite sheared off. It looks raw.

To help people cope, the state built the Old Man of the Mountain Memorial Plaza at the base of the mountain. It’s actually pretty clever. They installed these "Profilers"—steel poles with weirdly shaped metal cutouts on top. If you stand at a certain height and look through the sights, the metal shape aligns with the cliffside to recreate the silhouette of how the Old Man used to look.

It’s a ghost. A literal visual ghost of the past.

- The Museum: There’s a small museum at the Cannon Mountain Tramway that houses the original turnbuckles and pieces of the mountain.

- The Hike: You can hike to the top (the "Old Man's forehead"), but be warned: it’s a steep, rocky scramble that’ll leave your calves screaming.

- The Lake: Profile Lake sits right below the site. It’s quiet. It’s still one of the best places in the state to catch brook trout, even if the "Old Man" isn't watching over your shoulder anymore.

Why We Still Care

The Old Man was first "discovered" by white settlers in 1805 (Francis Whitcomb and Luke Brooks), though the Indigenous Abenaki people certainly knew about it long before. Daniel Webster, the famous statesman from New Hampshire, once wrote about how God hangs out signs to show what kind of "men" he makes in different regions. In New Hampshire, he said, God hung a sign of a man in stone.

That quote is everywhere up here. It’s on the walls of the state house. It’s in the heart of every local.

The Old Man of the Mountain represented a certain kind of New England grit. He looked grumpy. He looked tough. He looked like he’d survived a thousand winters—which he had. When he fell, it felt like the end of an era. But it also reinforced the "Live Free or Die" spirit. We don't need a fake rock to remember who we are.

Moving Forward Without the Face

If you’re planning a trip to see the site, don't go expecting a theme park. It's a place of reflection now. You go there to realize that even the mountains are temporary. It’s a bit of a reality check.

✨ Don't miss: Why the New York Marriott Marquis Elevator System is Still a High-Tech Marvel

Practical Steps for Your Visit:

- Check the weather: Franconia Notch creates its own microclimate. It can be 70 degrees in Lincoln and 45 degrees at the Notch. Bring a windbreaker.

- Use the Bike Path: Instead of just driving to the viewing area, park at the Flume Gorge and bike the Franconia Notch Recreation Path. It takes you right past the memorial and it's way more scenic.

- Visit the Flume: While you're there, hit the Flume Gorge. It’s a natural chasm with 90-foot granite walls. It’s just as impressive as the Old Man was, and it's actually still standing.

- Stop at the Basin: Just south of the Old Man site is a giant granite pothole worn smooth by the Pemigewasset River. It’s a great spot for photos and a reminder of the power of water—the same power that took the Old Man down.

The face is gone, but the mountain remains. Cannon Mountain is still one of the best ski hills in the East, and the hiking in the Franconia Range is world-class. You don't come for the rock anymore; you come for the history and the sheer, vertical scale of the place. Just don't ask a local if they're going to glue it back together. They've heard that one enough.