It started with a flea. Just one tiny, itchy bite from a parasite carrying a rod-shaped bacterium called Yersinia pestis. Most people think of the plague in medieval times as a sudden, supernatural curse that wiped out the world in a week, but the reality was a slow-motion train wreck that lasted years. It crawled along trade routes. It hopped from silk bales to grain sacks.

Honestly, the sheer scale is hard to wrap your head around. Between 1347 and 1351, Europe lost somewhere between 30% and 60% of its entire population. Imagine walking down your street and realizing half the houses are just... empty. That wasn't a horror movie plot; it was Tuesday in Florence in 1348.

🔗 Read more: Dark spots on black skin: Why your melanin reacts this way and how to actually fix it

How the Plague in Medieval Times Actually Spread

You’ve probably heard the "rat" theory a thousand times. While rats were definitely the primary hosts for the fleas, recent research from the University of Oslo suggests that human fleas and body lice might have been even more to blame for the rapid spread within cities. Basically, once it got into a crowded medieval slum, it didn't even need the rats anymore. It just jumped from person to person.

The hygiene wasn't the only issue. The climate played a massive role, too. Historians like Ole Jørgen Benedictow point out that a series of cold, wet winters in the 1330s led to crop failures. People were already hungry. Their immune systems were trashed. When the plague in medieval times finally arrived via the Black Sea and Sicily, it found a population that was physically unable to fight back.

It wasn't just one disease, either. We usually talk about "the plague" as a single thing, but it manifested in three distinct, gruesome ways:

- Bubonic: This is the one everyone knows. Large, painful swellings called buboes appeared in the groin or armpits. If you were lucky, they broke and drained. If not, you died of sepsis.

- Pneumonic: This version hit the lungs. It was airborne. You coughed, you sprayed bacteria, and the next person caught it. This was almost 100% fatal.

- Septicemic: This was the rarest and deadliest. The bacteria went straight into the bloodstream. People often died before they even realized they were sick.

The Weird Science and Failed Cures

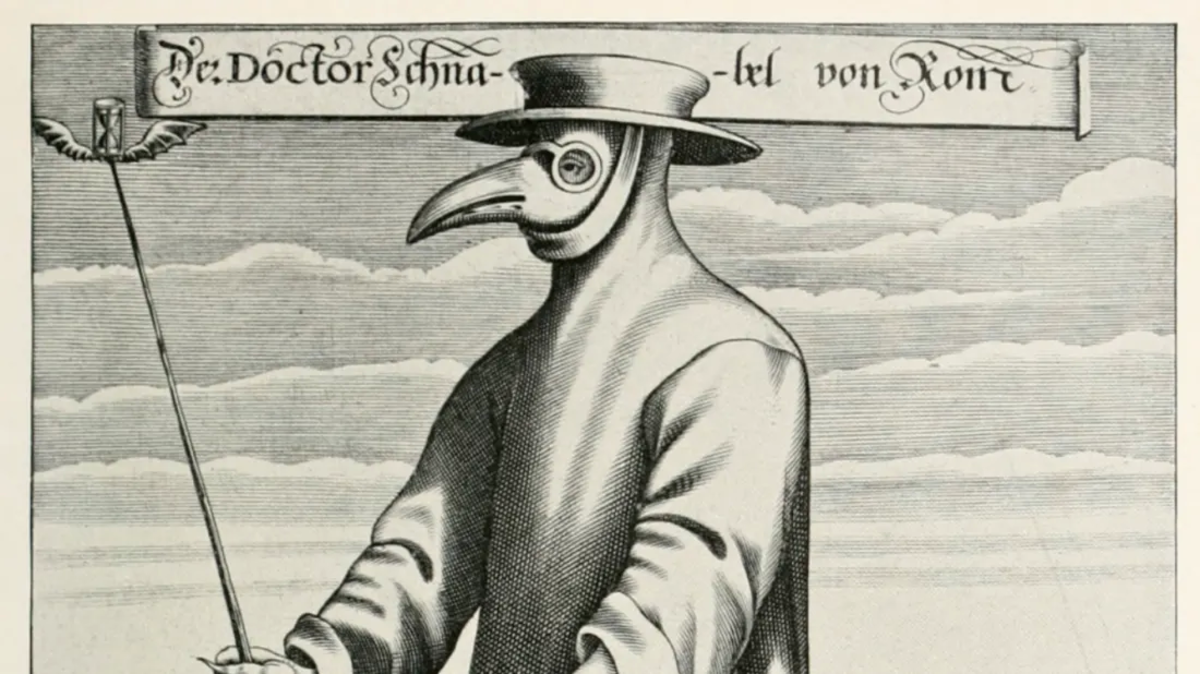

Medieval doctors weren't stupid, but they were working with a totally different map of the world. They believed in "miasma"—the idea that bad smells caused disease. This is why you see those iconic (and honestly terrifying) plague doctor masks filled with lavender and spices. They thought if they couldn't smell the rot, they wouldn't catch the death.

📖 Related: Not Drinking Alcohol Benefits: Why Your Body Actually Heals Faster Than You Think

They tried everything. Some people were told to sit in a room between two massive fires to "purify" the air. Others were prescribed "Theriac," a bizarre concoction that sometimes included ground-up snakes and opium. It didn't work. Obviously.

Then there were the flagellants. These were groups of people who wandered from town to town, whipping themselves in public. They believed the plague in medieval times was a punishment from God, and if they suffered enough, God would stop the killing. Instead, they just moved from town to town, bleeding on things and—you guessed it—spreading the bacteria even further.

Why the Plague in Medieval Times Changed Everything

We often focus on the death toll, but the aftermath was where the world actually shifted. Before the Black Death, Europe was stuck in a rigid feudal system. Peasants were essentially tied to the land. They had no power. They had no money.

Then, suddenly, there weren't enough workers.

If you were a landlord with a field of wheat rotting in the sun, and there were only five laborers left in the village instead of fifty, those five laborers had all the leverage. They started demanding higher wages. They moved to different towns for better deals. This was the beginning of the end for serfdom. It was the birth of a middle class.

Economic Chaos and the Silver Lining

Prices for food actually dropped because there were fewer mouths to feed, while wages for skilled trades skyrocketed. It was a weird, macabre kind of prosperity for the survivors.

💡 You might also like: Why a Tibia and Fibula Labeled Anatomy Diagram Explains Your Chronic Leg Pain

- Land Use: Huge swaths of farmland were abandoned and turned into sheep pastures because sheep required less labor than grain.

- Education: So many priests and teachers died that the Church had to start recruiting whoever was left, leading to a decline in Latin literacy and a rise in local languages like English and Italian.

- Technology: With fewer human hands available, people had to get creative. This period saw a massive spike in labor-saving inventions, eventually leading toward the printing press and better water mills.

The Religious Crisis

People’s faith was shaken to the core. They saw the "holy" dying just as fast as the "sinners." When bishops and monks fled cities to save themselves, the common people noticed. This created a massive vacuum of spiritual authority that eventually paved the road for the Reformation. If the Church couldn't save you from a flea, why should they tell you how to live your life?

Misconceptions We Need to Drop

First off, the "Plague Doctor" mask? That wasn't really a thing during the 1340s. That outfit was actually designed by Charles de Lorme in 1619. During the medieval peak, doctors mostly just wore long robes and hoped for the best.

Secondly, people weren't "dirty" by choice. Medieval people actually loved bathhouses. The problem was that the bathhouses became prime zones for transmission. When the plague hit, many cities closed the baths because they thought the heat opened the pores to the "bad air," which—ironically—made people stop washing, which made the lice and flea problem even worse.

Assessing the Damage

The numbers are staggering. In London, the population plummeted. In Paris, it’s estimated 800 people died every single day at the height of the outbreak. We see the scars of the plague in medieval times in the DNA of modern Europeans. A study published in Nature suggested that the survivors of the Black Death passed on specific immune system genes (like variations in the ERAP2 gene) that helped them survive the bacteria, but those same genes might be linked to autoimmune diseases like Crohn's today.

History literally lives inside us.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to understand this era beyond the surface level, don't just look at death counts. Look at the shifts in art and literature. After the 1350s, European art became obsessed with "The Dance of Death" (Danse Macabre).

- Visit Local Archives: If you live in Europe, many parish records from the 14th century are digitized. Look for sudden gaps in the records—that's usually where the plague hit.

- Trace Trade Routes: Map the spread of the plague against the Silk Road. You’ll see it follows the movement of wealth and luxury goods perfectly.

- Read Primary Sources: Look up The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio. He lived through the plague in Florence and wrote about people hiding in villas to escape the rot. It’s the closest thing we have to a "blog" from the front lines.

- Check the DNA: Look into recent bio-archaeological studies from "plague pits" like the one found at East Smithfield in London. These provide the most accurate data on who died and how healthy they were before the infection.

The Black Death was a horror, but it was also a reset button. It broke a stagnant world and forced it to modernize. We are, in many ways, the descendants of the people who were tough enough—or lucky enough—to survive the worst thing that ever happened to the human race.

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

- Research the "Great Famine of 1315" to see how the environmental collapse set the stage for the pandemic.

- Compare the 14th-century outbreak with the "Plague of Justinian" (6th century) to see how the bacteria evolved.

- Use the Paleobiology Database to look at how rodent populations shifted during climate changes in the medieval period.