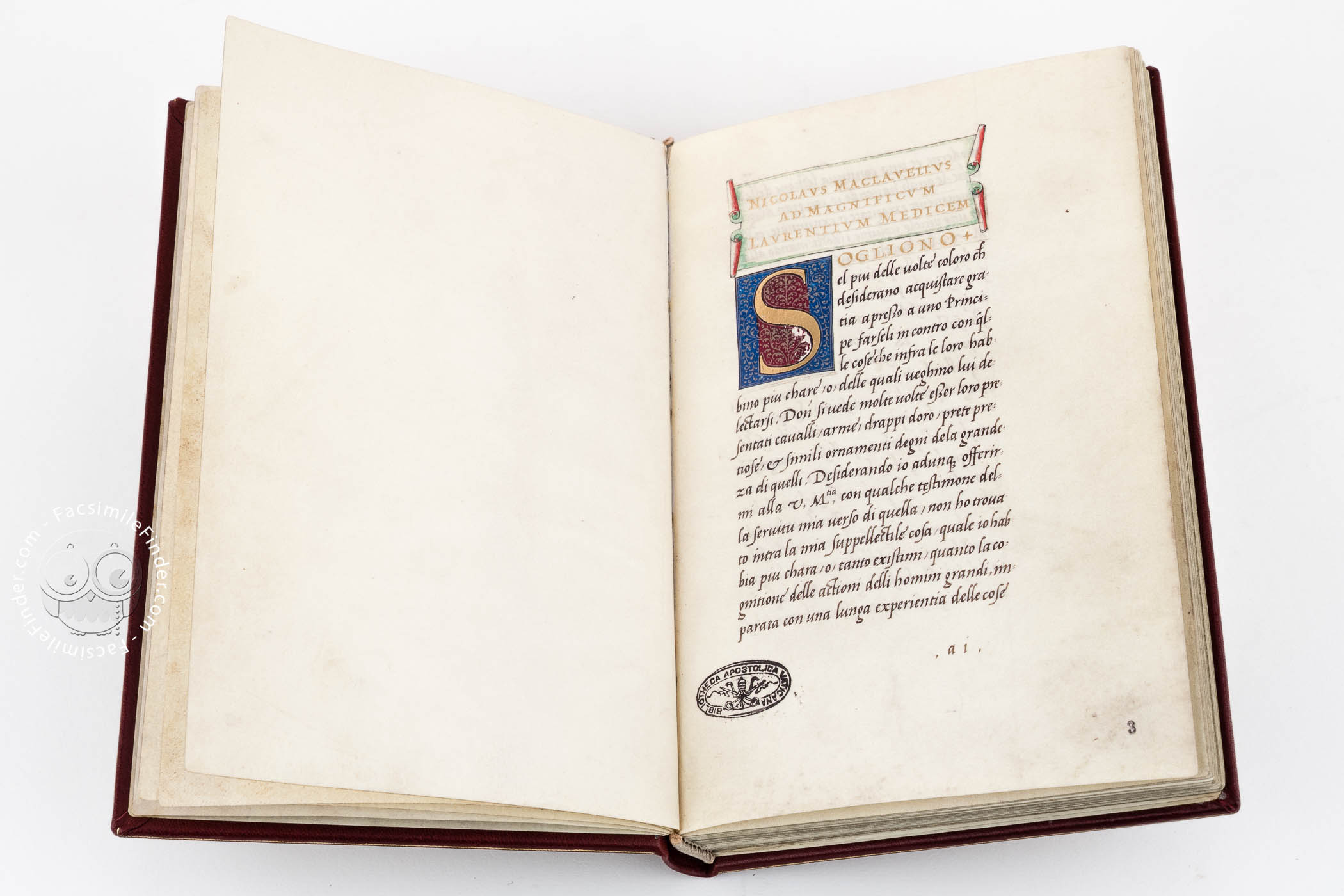

Niccolò Machiavelli was in a bad spot when he wrote his masterpiece. It was 1513. He'd been tortured, kicked out of his government job in Florence, and basically forced into a boring retirement at a farm. He was desperate. He wanted his old life back. So, he wrote a "job application" of sorts to the Medici family, who had just taken power. That application was The Prince. Most people think it's a manual for being a complete jerk, but that's a huge oversimplification. Honestly, it's more like a cold splash of water to the face for anyone who thinks politics is about being a nice person.

What The Prince by Machiavelli Actually Says

People love to use the word "Machiavellian" as an insult. They think it means being a mustache-twirling villain who loves backstabbing. But if you actually read The Prince by Machiavelli, you'll see he isn't necessarily saying "be evil." He's saying "be effective." He lived in a time when Italy was a mess of warring city-states, foreign invasions, and constant betrayal. To him, a weak leader was a dangerous leader because a weak leader let the state fall into chaos.

Take his most famous question: is it better to be loved or feared? Most of us want to say "loved," right? Machiavelli argues that while being both is ideal, if you have to choose, pick fear. Why? Because people are fickle. They’ll love you when things are going great, but the moment they have to sacrifice something for you, they'll turn. Fear, however, is held by the dread of punishment, which never fails. But—and this is a big but—he warns that you must avoid being hated. If the people hate you, they'll revolt, and then you're done.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Guy Is Wearing a Lava Rock Bracelet for Men Right Now (And How to Not Buy a Fake)

The Fox and the Lion

Machiavelli uses this great analogy about the fox and the lion. A prince needs to be both. The lion is strong and can scare off wolves, but he’s dumb and falls into traps. The fox is smart and sees the traps, but he can't fight off wolves. You have to be both. You need the strength to enforce your will and the cunning to see the political traps being set for you.

He also talks about virtù and fortuna. This isn't "virtue" in the religious sense. For Machiavelli, virtù is more like "manliness" or "prowess"—the ability to take control of a situation through sheer will and talent. Fortuna is luck or fate. He famously compares fortuna to a violent river. You can't stop the flood, but a leader with virtù builds dams and dikes during the dry season so the flood doesn't destroy everything.

Why the Church Hated Him

For centuries, The Prince was on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum—the list of books the Catholic Church banned. Why? Because Machiavelli did something radical. He separated ethics from politics. Before him, political philosophers like Plato or Thomas Aquinas argued that a leader should be the most virtuous, godly person possible. Machiavelli called nonsense on that. He observed that "good" people often get crushed by "bad" people who don't play by the rules. If you’re a leader, your primary job is to keep the state safe. If that requires lying or being a bit ruthless, Machiavelli says that's the price of admission.

Modern Myths About The Prince

One of the biggest misconceptions is that Machiavelli wrote this for everyone. He didn't. He wrote it for "New Princes"—guys who had just seized power and didn't have the benefit of a long-standing family dynasty to keep the people in line. If you're a king whose family has ruled for 300 years, the people are used to you. You can be a bit lazy. But if you're a new guy, you're vulnerable. You've got to be extra sharp.

Another myth? That he was a fan of dictators. Later in his life, Machiavelli wrote Discourses on Livy, where he basically argued that a republic (where people have a say) is actually the best form of government. So why the shift? Some scholars, like Erica Benner, argue that The Prince might actually be a satire or a warning to the people about how tyrants behave. Others think he was just being a pragmatist: "Look, if we’re going to have a prince, he might as well be a competent one so we stop getting invaded by France and Spain."

Real-World Examples of Machiavellianism

Look at history. Think about Cesare Borgia. Machiavelli actually knew this guy and uses him as a primary example in the book. Borgia was ruthless. He once hired a guy named Remirro de Orco to clean up a lawless province. De Orco did it—using brutal, bloody methods. Once the province was orderly, Borgia knew the people hated De Orco for his cruelty. So, Borgia had De Orco cut in half and left in the town square. It showed the people that the "cruelty" wasn't Borgia's fault, and it made them both grateful and terrified.

Is that "evil"? By our standards, absolutely. By Machiavelli’s? It was a masterful political move that stabilized a region and consolidated power without making the leader the target of the people's rage.

🔗 Read more: Black natural hairstyles for wedding: Why simple is usually better

How to Apply Machiavelli Without Being a Sociopath

You don't have to be a warlord to learn something here. In the modern world—whether it's business or just navigating a tough social environment—certain "Machiavellian" principles actually make sense.

- Don't outsource your security. Machiavelli hated mercenaries. He thought if you didn't have your own army, you weren't really in control. In life, if you rely too much on others for your basic needs or your professional reputation, you’re at their mercy.

- The "Band-Aid" rule. Machiavelli says if you have to do something "harmful" (like layoffs in a company), do it all at once. People have short memories for sharp pain, but they'll resent you forever if you drag it out over months of small "injuries."

- Be present. He argued that a prince who lives in a newly conquered territory is much harder to lose. In management, this is basically "leading from the front." If you aren't there to see what's happening, you're getting filtered information.

The Bottom Line

Machiavelli wasn't trying to create a world of villains. He was trying to describe the world as it actually is, not as we wish it would be. He’s the father of "realpolitik." Whether you love him or hate him, The Prince by Machiavelli forces you to answer a hard question: what are you willing to sacrifice to get things done?

If you want to understand power, you sort of have to deal with Niccolò. He’s the guy in the corner of the room pointing out that the emperor has no clothes—and then suggesting the emperor might want to buy a very sharp sword just in case.

💡 You might also like: Marc Jacobs Dot Fragrance: Why This Ladybug Bottle Still Dominates Your Vanity

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

- Audit your dependencies. Identify areas in your career where you rely on "mercenaries"—people or tools that could leave you stranded. Start building your own "citizen militia" of skills and direct relationships.

- Execute tough decisions quickly. If you have to deliver bad news or make a structural change, don't prolong the process. Do it decisively to allow the "healing" phase to begin immediately.

- Master the Fox/Lion balance. Recognize when a situation requires raw effort and "lion-like" presence versus when it requires "fox-like" diplomacy and careful observation.

- Study the Discourses. To get the full picture of Machiavelli's mind, read his Discourses on Livy. It provides the necessary balance to the cold pragmatism found in The Prince.

- Watch the "Hate" threshold. In any leadership role, you can survive being unpopular, but you cannot survive being loathed. Monitor your reputation to ensure you aren't crossing the line into "hated" territory, which usually happens through the seizure of property or perceived personal insults.