Alfred Hitchcock stole the show. Most people hear the word "Psycho" and immediately think of a screeching violin, a swirling drain, and Janet Leigh’s wide, dead eyes. But before the shower scene became a cinematic blueprint, there was the Psycho book by Robert Bloch. Published in 1959, it was a lean, mean, and surprisingly grimy piece of Midwestern gothic fiction. It didn't just appear out of nowhere. Bloch, who was living in Weyauwega, Wisconsin at the time, was writing just thirty-five miles away from Plainfield—the home of the notorious Ed Gein.

Gein was the real-life "ghoul" who inspired Norman Bates. Sorta.

Bloch actually started writing the book before the full, stomach-turning details of Gein's crimes were public knowledge. He just knew that a quiet, unassuming man in a small town had been caught with bodies in his house. This realization—that the "boy next door" could be a monster—became the heartbeat of the story. If you've only seen the movie, the original text feels like a punch to the gut. It’s tighter. It's meaner. Honestly, it’s a lot weirder than the Hollywood version.

Forget the Norman Bates You Think You Know

In the film, Anthony Perkins is lanky, nervous, and awkwardly charming. He’s the kind of guy you might feel sorry for. In the Psycho book by Robert Bloch, Norman is a mess. He’s middle-aged, overweight, and wears thick glasses. He’s an alcoholic who suffers from "blackouts" and has a deep interest in the occult and psychology. He isn't a shy boy. He's a ticking time bomb of repressed resentment and bitter isolation.

The book gives us a front-row seat to Norman’s inner monologue. It’s claustrophobic. You’re trapped inside the mind of a man who is constantly arguing with his mother’s voice.

🔗 Read more: The Little Witch: Why This German Fantasy Still Casts a Spell on Families

Bloch doesn't play fair with the reader. He uses a technique called "misdirection" that is way harder to pull off on the page than on screen. Because we see Norman’s thoughts, we assume we’re getting the whole truth. We aren't. Bloch layers the narrative so that the "Mother" persona is just as vivid and "real" in the prose as Norman himself. It makes the final reveal feel less like a plot twist and more like a psychological collapse.

The Shock That Changed Fiction

Mary Crane—renamed Marion in the movie—is our protagonist for the first third of the story. We follow her through the theft of $40,000. We feel her guilt. We see her drive through the rain, desperate for a place to hide. When she pulls into the Bates Motel, the reader is settled into a standard crime thriller.

Then Bloch kills her.

It was unheard of in 1959. You didn't just kill your lead character forty pages in. This isn't just about the gore; it’s about the narrative betrayal. By removing the moral center of the book, Bloch leaves the reader stranded with Norman. We are forced to watch him clean up the mess. We become accomplices. Bloch was a student of H.P. Lovecraft, and you can see that cosmic nihilism creeping in here. The world of Psycho isn't one where justice is guaranteed. It’s a world where a wrong turn in a rainstorm leads to a senseless, sudden end.

Why Bloch’s Prose Matters More Than the Gore

Bloch was a master of the "pulps." He knew how to move a story fast. But he also understood the power of a single, haunting image. Take the way he describes the Bates house. It’s a "tall, hideously Victorian" structure that seems to watch the road. In the book, the house feels like a living extension of Norman’s psyche. It’s cluttered, rotting, and full of secrets that Norman himself doesn't fully understand.

The violence in the Psycho book by Robert Bloch is actually more graphic than what Hitchcock was allowed to show on screen. In the novel, Mary is decapitated. It’s a brutal, clinical description that strips away any sense of "glamour" from the murder. Bloch wasn't interested in making a beautiful film; he was interested in the ugly reality of a psychotic break.

He also explores themes that the 1960s film had to dance around. There’s a lot more explicit talk about transvestism and the specific mechanics of Norman’s "Mother" persona. While the film treats it as a shocking "case study" at the end, the book treats it as a tragic, inevitable conclusion to a lifetime of abuse and stifling isolation.

The Ed Gein Connection: Fact vs. Fiction

People always ask how much of the Psycho book by Robert Bloch is "true."

The answer is: less than you think, but more than is comfortable. Bloch didn't research Gein's life to write Norman. Instead, he imagined what kind of environment would create a man like that. When the details of Gein’s "house of horrors" finally came out—the lampshades made of skin, the seats upholstered with human remains—Bloch was stunned by how close his fictional Norman was to the real-life killer.

- Gein had a dominant, fanatically religious mother.

- Gein lived in isolation after her death.

- Gein created a "woman suit" to literally step into her identity.

Bloch tapped into a specific American anxiety of the late 50s. The suburbs were growing. The "nuclear family" was the ideal. But behind those white picket fences and at the end of those lonely old highways, something was festering. Norman Bates was the personification of the rot beneath the post-war American dream.

Reading Psycho Today: Is It Still Scary?

In a world of "slasher" movies and true crime podcasts, you might think a 65-year-old book would lose its edge. It hasn't. The reason is simple: Bloch focuses on the "why" more than the "how."

The horror of the Psycho book by Robert Bloch isn't the knife. It’s the realization that the person talking to you might not even know who they are. It’s the psychological disintegration. The final lines of the book—Mother’s internal monologue while a fly crawls on Norman’s hand—are some of the most chilling in horror literature. It’s a masterpiece of cold, detached irony.

If you’ve only seen the movie, you’re missing half the story. The book offers a much darker, more cynical view of the world. There’s no easy sympathy for Norman here. There’s only the cold, hard reality of a broken mind in a lonely house.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Melissa McCarthy Identity Thief

How to Experience the Story Properly

If you're looking to dive back into the world of Norman Bates, don't just re-watch the movie. Start with the text. Here is how to get the most out of it:

- Read the original 1959 novel first. Ignore the sequels Bloch wrote later (Psycho II and Psycho House), as they take a very different, more satirical direction that diverges wildly from the movies.

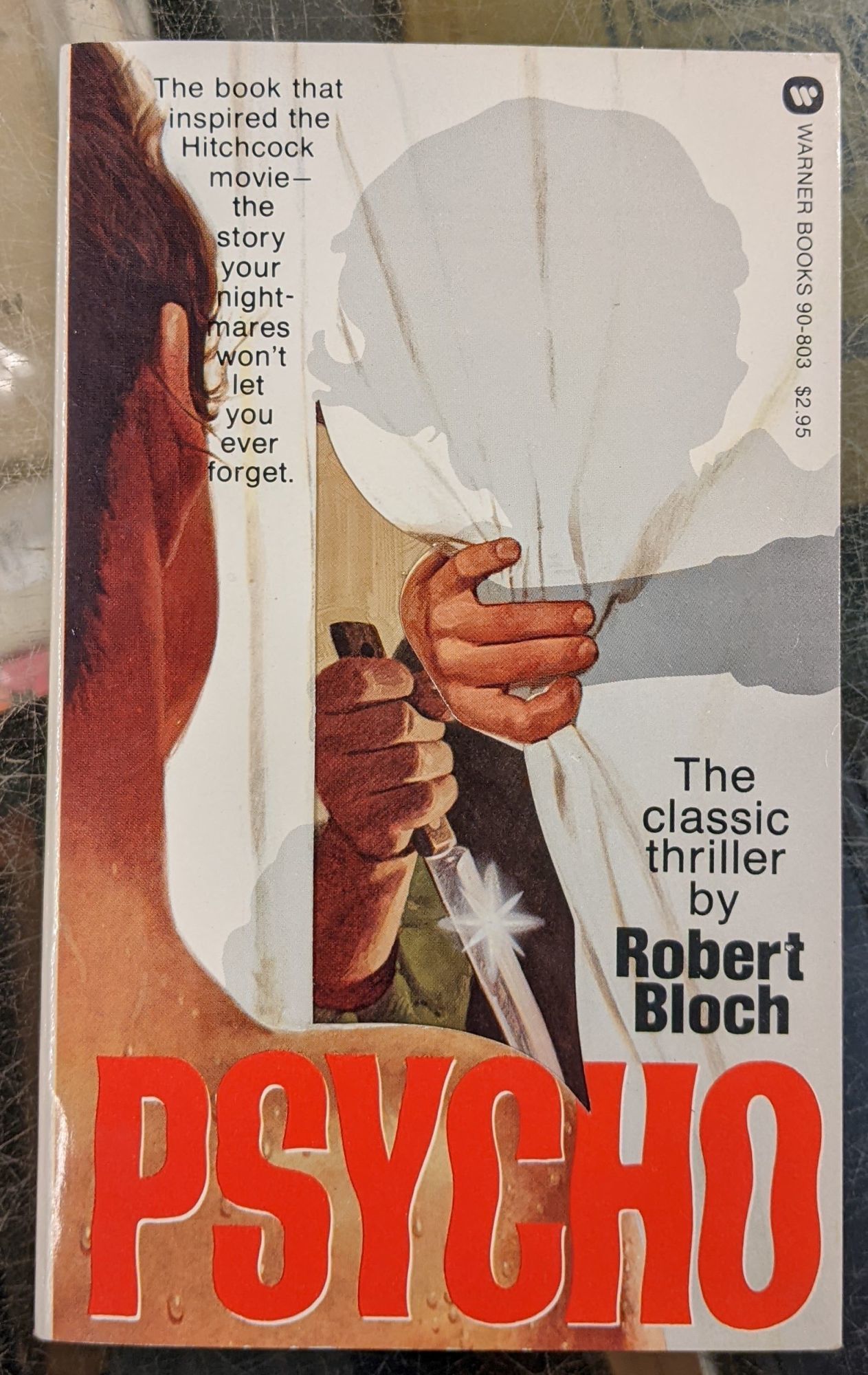

- Look for the "Inner Sanctum" mystery editions. These often have great vintage cover art that captures the pulp feel Bloch was aiming for.

- Compare the "Dr. Richmond" scene. In the movie, the psychiatrist's explanation at the end feels a bit long-winded. In the book, the clinical breakdown of Norman’s "three personalities" is handled with a much sharper, more disturbing edge.

- Pay attention to the weather. Bloch uses the storm not just for atmosphere, but as a physical barrier that traps Mary in Norman’s world. It’s a classic "no exit" scenario.

The Psycho book by Robert Bloch remains a foundational text of modern horror because it stopped looking for monsters in the shadows and started looking for them in the mirror. It’s a quick read, usually under 200 pages, but it stays with you long after you close the cover. It reminds us that the scariest places aren't haunted houses—they're the quiet motels at the end of the road where the light is always on, but nobody's really home.