Accountants aren't magic. Honestly, they just have a better mental map of where money moves than the rest of us do. When you're staring at a chaotic pile of receipts or a QuickBooks dashboard that makes zero sense, you need a way to strip away the noise. That's where a t accounts cheat sheet becomes your best friend. It’s basically the "back of the napkin" version of double-entry bookkeeping. It doesn’t look like much—just a big letter "T" on a page—but it is the DNA of every financial statement ever written.

Think about it. Every single transaction in business affects at least two things. If you buy a laptop, you have more equipment, but you have less cash. If you sell a service on credit, you have more revenue, but you also have an "I.O.U." from a customer. This duality is what trips people up. Most people try to track money like a checkbook, just adding and subtracting from one pile. That’s a recipe for a balancing disaster.

The Anatomy of the T Account

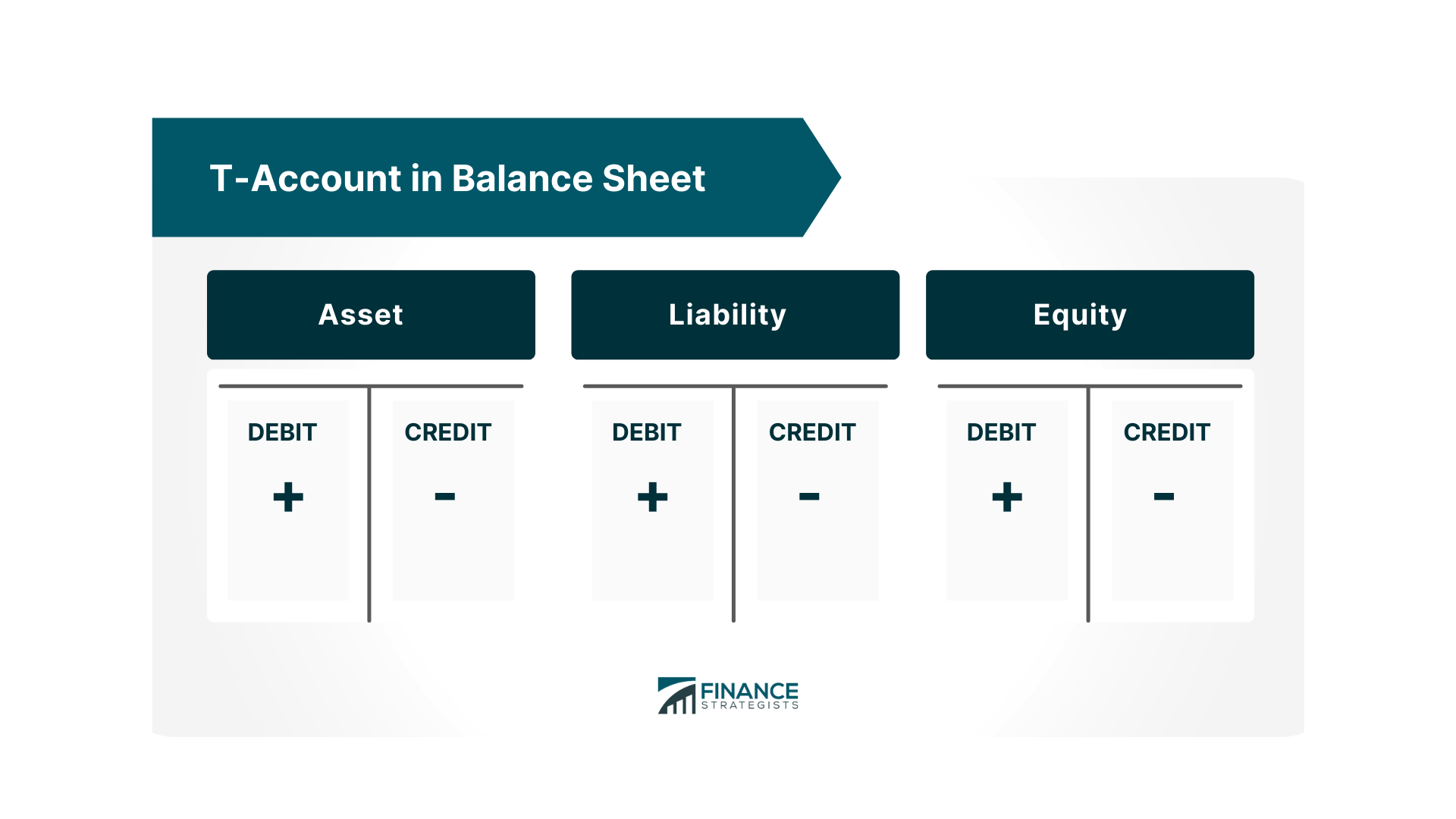

You’ve got the name of the account at the top. Underneath that, a vertical line and a horizontal one. It’s a T. The left side is always, 100% of the time, the Debit side. The right side is always the Credit side. People get weirdly emotional about these terms. They think "credit" means something good, like a credit card reward, and "debit" means something bad, like money leaving your bank account.

Forget that.

In the world of accounting, debit just means "left" and credit just means "right." That's it. There is no moral value attached to either side. Depending on what kind of account you're looking at—an asset, a liability, or equity—a debit might increase the balance or decrease it. It feels like a riddle until you see the pattern.

The DEALER Rule

If you want a t accounts cheat sheet that actually sticks in your brain, remember the acronym DEALER. It’s the easiest way to keep your lefts and rights straight without having to call your CPA every twenty minutes.

The first three letters—Dividends (or Drawings), Expenses, and Assets—behave the same way. When these go up, you put the number on the Debit (Left) side. If you buy a new truck (Asset), that's a debit. If you pay your rent (Expense), that's a debit.

The last three letters—Liabilities, Equity, and Revenue—are the opposite. They increase on the Credit (Right) side. If you take out a loan (Liability), you credit that account. If you land a massive consulting contract and get paid (Revenue), you credit that account.

It’s symmetrical. It’s logical. It’s also incredibly easy to flip if you’re tired.

Putting the T Accounts Cheat Sheet into Practice

Let’s look at a real-world scenario. Say you start a small coffee shop called "The Daily Grind." You put $10,000 of your own savings into the business bank account.

How does that look on your t accounts cheat sheet?

First, your Cash account (an Asset) goes up. Since assets increase with debits, you put $10,000 on the left side of the Cash T account. But wait—double-entry means we need a matching entry. Since this is your own money, your Owner’s Equity account also goes up. Equity increases with credits, so you put $10,000 on the right side of the Equity T account.

Debits ($10,000) = Credits ($10,000). The universe is in balance.

Now, imagine you buy $2,000 worth of espresso machines on credit from a supplier. You aren't paying cash yet. You have a new Asset (Equipment), so you debit that account for $2,000. But since you owe that money, you have a new Liability (Accounts Payable). You credit Accounts Payable for $2,000.

Most software hides this from you. It gives you a nice "Enter Bill" button and does the math in the background. But when the software glitches or you make a data entry error, you’re lost unless you can visualize these T accounts. Knowing the manual flow allows you to troubleshoot the digital mess.

Why Beginners Always Get Confused by Bank Statements

Here is the thing that breaks everyone's brain: your bank statement.

When you look at your personal bank app, a "deposit" is a credit. But I just told you that for a business, cash (an asset) increases with a debit. Why the contradiction?

It’s all about perspective. To the bank, your money is a liability. They owe that money back to you. When you give them $100, their liability to you increases. And how do liabilities increase? With a credit. So, when the bank says "we credited your account," they are speaking from their ledger, not yours. If you are keeping your own books, that same $100 is a debit to your cash account.

Understanding this distinction is usually the "aha!" moment for most business owners. It’s the difference between being a passive consumer of financial data and actually understanding the mechanics of your business.

The Role of the Trial Balance

Once you’ve filled out your T accounts for the month, you don’t just leave them hanging. You "foot" them. This is just a fancy way of saying you add up both sides and find the difference.

If your Cash account has $15,000 in debits (money coming in) and $8,000 in credits (money going out), your "normal balance" is a $7,000 debit. You then take all these final balances and list them on a Trial Balance.

If the total of all your debit balances doesn't equal the total of all your credit balances, you've got a problem. Maybe you posted a $500 utility bill as a $50 credit instead of a $500 debit. Maybe you forgot to record the second half of a transaction entirely. The T account makes these errors jump off the page. It's like a spell-checker for your finances.

Common Pitfalls to Watch Out For

- Reversing the Entry: This is the most common mistake. You know the amount is $400, but you put it on the credit side instead of the debit side. Your trial balance will be off by exactly double the amount of the error ($800). If you see a discrepancy that is an even number, look for a reversed entry first.

- Transposition Errors: Writing $540 instead of $450. A quick trick? If the difference between your debits and credits is divisible by 9, you probably transposed some numbers.

- Forgetting the "Other Side": Beginners often record the cash leaving the bank but forget to categorize what it was spent on. Every T account needs a partner.

Advanced Nuance: Contra Accounts

Not every account plays by the standard DEALER rules. Enter the Contra Account. These are the rebels of the accounting world.

Take "Accumulated Depreciation." It’s technically an asset account because it sits with your equipment and machinery. However, its job is to reduce the value of those assets over time. Because it reduces an asset, it has a "normal credit balance."

Similarly, "Sales Returns and Allowances" is a contra-revenue account. It reduces your total sales. Since revenue usually has a credit balance, this account has a debit balance. If you're building a t accounts cheat sheet, you have to mark these outliers clearly, or they will wreck your reports.

Modern Relevance of the T Account

You might think T accounts are obsolete in the age of AI and cloud accounting. They aren't.

University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School still drills these into MBA students for a reason. When a company like Enron or more recently, complex crypto exchanges, run into trouble, it usually involves "creative" bookkeeping that obscures the basic T account flow. If you can’t draw a T account for a transaction, you probably don’t understand the transaction.

For a small business owner, using a T account is a mental exercise in clarity. Before you click "save" on a complex journal entry in your software, sketch it out. Does it actually make sense? Is the equity actually increasing, or are you just masking an expense?

Actionable Steps for Mastering T Accounts

- Start a "Scratch" Ledger: Before you enter anything into your formal software this week, grab a piece of paper. Draw a T. Label one side Cash and the other side Revenue or Expense. Physically write the numbers in.

- Audit Your Last Three Mistakes: Look at the last time you had to "force" a reconciliation in your bank feed. Draw the T accounts for what actually happened versus what you recorded. You’ll likely see exactly where your logic tripped up.

- Memorize the Normal Balances: Don't try to figure it out every time. Just memorize that Assets and Expenses are debits; Liabilities, Equity, and Revenue are credits. Use the DEALER mnemonic until it’s second nature.

- Use T Accounts for Budgeting: Instead of just a list of numbers, try mapping out your planned spending using the T structure. It helps you see how a "save" in one area (a credit to an expense account) can be a "gain" elsewhere (a debit to a savings asset).

Accounting is a language. The T account is the alphabet. Once you know the letters, you can start reading the story your business is trying to tell you.

👉 See also: Naira Against US Dollar: Why It Keeps Moving and What it Means for Your Pocket

Next Steps for Accuracy

To ensure your financial records are flawless, verify your T account balances against your bank statements monthly. If you find a discrepancy, use the "Divide by 9" rule to check for transposed numbers before re-examining every individual transaction. This simple verification step prevents small errors from snowballing into major tax-season headaches.