You’ve probably seen those posters. The ones with the clean, blue lines tracing a few major arteries like the Mississippi or the Colorado. Honestly, they’re lying to you. A real united states map with all rivers isn't a neat diagram; it’s a chaotic, pulsing capillary system that looks more like a human nervous system than a piece of geography. If you actually plotted every single perennial stream and river in the lower 48, the map would be almost entirely blue.

Water is everywhere.

Even in the bone-dry patches of the Mojave or the high deserts of Nevada, the land is etched with the memory of flow. Most people think of "rivers" as these massive, navigable things you can put a barge on. In reality, the vast majority of our national water map is made up of "first-order" streams—tiny, nameless creeks that start in a backyard or a mountain fold and eventually feed into the giants.

What a United States Map With All Rivers Actually Tells Us

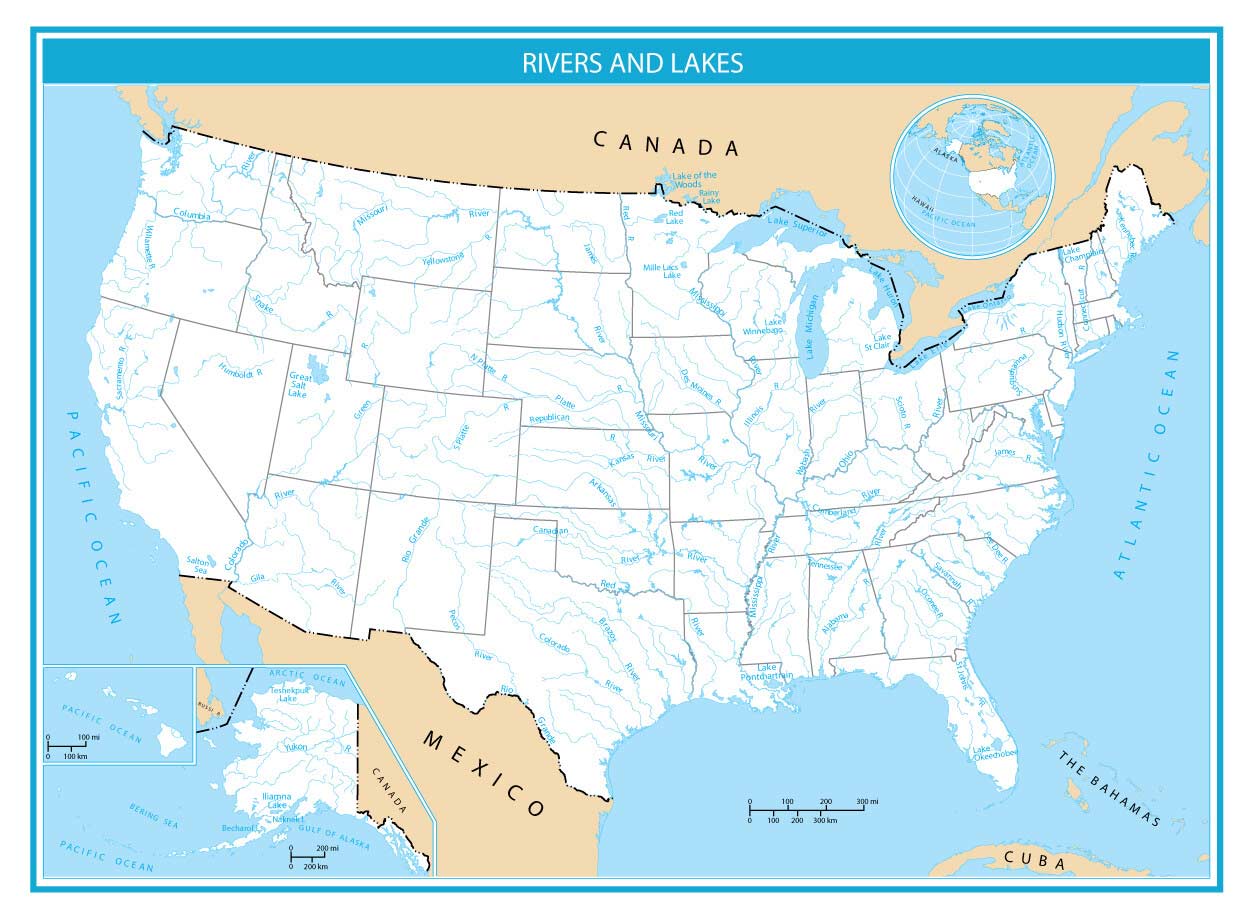

When you look at a truly high-resolution united states map with all rivers, the first thing you notice is the "Great Divide." It's not just a hiking trail. It’s the literal backbone of the continent. Every drop of rain that hits the dirt on one side goes to the Pacific; every drop on the other heads toward the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico.

Take the Mississippi River Basin. It’s huge. It drains about 40% of the continental United States. If you’re looking at a detailed map, you’ll see the Missouri River snaking in from the west and the Ohio River coming in from the east. They look like massive tree branches. But look closer. You’ll see the Platte, the Arkansas, the Tennessee, and the Red River. They all pile into that one central vein.

It’s kind of terrifying when you think about it. A chemical spill in a tiny creek in Montana can, theoretically, find its way down to the French Quarter in New Orleans. The map proves we are all much more connected than our state borders suggest.

The Weirdness of the Great Basin

There’s a giant hole in the map. Well, not a hole in the land, but a hole in the flow.

If you check out a united states map with all rivers, you’ll see a weird spot in the West—mostly Nevada, parts of Utah, and California—where the rivers just... stop. They don't go to the ocean. This is the Great Basin. Rivers like the Humboldt just kind of wander into the desert and evaporate or sink into "sinks." It’s a closed loop. It defies the logic we’re taught in grade school about everything flowing to the sea.

The Digital Cartography Revolution

How do we even make these maps now? We aren't sending guys out with transit levels and notebooks anymore.

We use LiDAR and the National Hydrography Dataset (NHD). The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) manages this massive database. It’s basically a digital blueprint of every blue line in the country. Geographers like Robert Szucs, who runs Grasshopper Geography, have turned this data into art. He creates these maps where different watersheds are color-coded.

When you see the United States mapped this way, you realize that state lines are basically imaginary. They don't follow the logic of the earth. The Tennessee River doesn't care that it’s crossing into Alabama. The Colorado River doesn't give a damn about the border with Mexico, though we’ve sucked it so dry with irrigation and city water needs that it barely reaches the sea anymore.

Why Scale Matters More Than You Think

If you go to a site like the USGS National Map, you can zoom in until you see the creek behind your local Walmart. That’s the "all rivers" part.

Most maps you buy at a gas station or see in a textbook are "generalized." Cartographers simplify the lines so your eyes don't get tired. But a raw united states map with all rivers shows roughly 3.5 million miles of channels. That is enough water to circle the Earth 140 times.

📖 Related: Finding Wallace Funeral Home Newton Iowa Obituaries: What to Know When You’re Searching

The Problem With "All"

Here is the kicker: what counts as a river?

Hydrologists argue about this constantly. Does a "wash" in Arizona that only flows for twenty minutes after a thunderstorm count? On a technical united states map with all rivers, we usually talk about "perennial" streams—those that flow year-round. But if you include "intermittent" or "ephemeral" streams, the map gets even denser.

In the East, the map is a thick blue carpet. The Appalachian Mountains are essentially a giant water-shedding machine. In the West, it’s different. The lines are longer and lonelier. You have the Columbia in the Northwest, which is an absolute powerhouse of hydroelectric energy. Then you have the Rio Grande, which is a political lightning rod but, in many places, is just a trickle compared to the mighty rivers of the East.

The Impact of Infrastructure

We’ve messed with the map.

You can't look at a united states map with all rivers today without acknowledging the dams. There are over 90,000 dams in the U.S. Every time we build one, we change the map. We turn a moving river into a series of stagnant lakes. The Columbia River, for example, is basically a staircase of reservoirs now. It’s efficient for power, but it’s a nightmare for the salmon that have been trying to navigate those "blue lines" for thousands of years.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re a hiker, a fisherman, or just someone who likes staring at maps, don't settle for the simplified versions.

- Check the USGS National Map Viewer. It’s free. It’s public data. You paid for it with your taxes. You can toggle "Hydrography" and see the real veins of the country.

- Look for Watershed Maps. Instead of looking at a map of "The USA," look for a map of the "Mississippi Basin" or the "Chesapeake Bay Watershed." It makes way more sense. It explains why some areas flood and why some are perpetually dry.

- Understand the "Strahler Stream Order." This is a fancy way geologists rank rivers. A "1" is a tiny headwater. When two "1s" meet, they become a "2." The Mississippi is a "10." It helps you understand the hierarchy of the water.

The reality of our landscape is much wetter and more complex than we usually admit. When you finally see a united states map with all rivers in its full, unedited glory, you stop seeing a collection of 50 states and start seeing a living, breathing ecosystem.

Stop thinking in terms of borders. Start thinking in terms of flow. The next time you cross a bridge, even a small one over a muddy creek, remember that you’re looking at a tiny part of a 3.5-million-mile network that keeps the entire continent alive. Go find a high-resolution watershed map from the USGS or a specialized cartographer and print it out. It’ll change how you see your next road trip across the country.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts

- Download the Raw Data: If you’re tech-savvy, head to the USGS National Hydrography Dataset. You can pull the GIS layers yourself and use free software like QGIS to create your own custom views.

- Identify Your Local Basin: Use the EPA's "How's My Waterway" tool. It uses the same mapping data to show you exactly which river system you live in and, more importantly, the health of that water.

- Support River Conservation: Organizations like American Rivers use these "all river" maps to identify which segments are "Wild and Scenic" and need federal protection from development.

- Observe Seasonality: Remember that any map is a snapshot. In the American Southwest, a map showing "all rivers" might include hundreds of miles of dry beds that only roar to life during monsoon season. Always cross-reference map data with real-time streamflow gauges if you're planning a trip.

The map isn't the territory, but a map with every river is as close as we get to seeing the heart of the land.