If you look at a US map during Civil War years, you aren't just looking at a division between North and South. It’s a mess. Honestly, the clean lines we see in high school textbooks—blue for the Union, red for the Confederacy—are kind of a lie. The actual geography of the 1860s was a shifting, bleeding pile of territorial disputes, "unorganized" lands, and military occupations that changed by the week.

Most people think the map was static from 1861 to 1865. It wasn't. It was alive.

West Virginia didn't even exist when the smoke cleared at Fort Sumter. Nevada was a tiny square that grew like a weed because the Union wanted its silver. While Lee and Grant were trading blows in Virginia, the federal government was frantically carving up the West to ensure the gold mines stayed out of Jefferson Davis’s hands. If you want to understand why the United States looks the way it does today, you have to look at the chaotic, desperate cartography of the 1860s.

The Myth of the Solid South

We talk about the "Confederacy" as this monolithic block. It looks solid on a map. But look closer at a US map during Civil War times and you'll see the "Border States." Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. These were slave states that stayed in the Union, and they make the map look incredibly weird.

Abraham Lincoln famously said he hoped to have God on his side, but he must have Kentucky.

Why? Because if Kentucky flipped, the Ohio River—the great internal highway of the mid-19th century—became a Confederate border. It would have been a logistical nightmare. For much of the war, the map of Kentucky was a patchwork of "neutral" zones and occupied towns. Missouri was even worse; it had two governments. One was the official Union-recognized body in Jefferson City, and the other was a pro-Confederate government-in-exile that the CSA actually counted as their 12th star on their flag.

Then there's the "State of Scott." Ever heard of it?

💡 You might also like: Quien gana las elecciones: Por qué las encuestas fallan y qué mirar realmente

Deep in the mountains of Tennessee, Scott County was so pro-Union that they literally seceded from Tennessee when Tennessee seceded from the Union. They declared themselves the "Free and Independent State of Scott." It wasn't officially recognized, but it shows how the US map during Civil War was less about state lines and more about local loyalties.

The West Was a Wild Card

While the headlines were in Gettysburg, the map was exploding out West.

The Confederacy actually had designs on the Pacific. In 1861 and 1862, they formed the "Confederate Arizona Territory." This wasn't the Arizona we know today. It was a horizontal slice of the bottom half of modern-day New Mexico and Arizona. They wanted a route to California's gold and the ports of San Diego.

The Battle for Glorieta Pass

Basically, the "Gettysburg of the West" happened in New Mexico. Had the Confederates won at Glorieta Pass, the US map during Civil War might have shown a Confederate corridor stretching all the way to the Colorado gold fields. Instead, the Union held, and the federal government quickly reorganized the territories into the vertical shapes we recognize now to break up any lingering Southern influence.

- Kansas had just become a state in January 1861, literally weeks before the war started.

- Nevada was fast-tracked to statehood in 1864, despite having almost no people, just so Lincoln could get more electoral votes and the Union could secure its mineral wealth.

- The Dakota Territory was a massive, sprawling chunk of land that included most of what is now Montana and Wyoming.

It was a land grab. The Union was using the war as an excuse to cement its grip on the continent.

West Virginia: The Map’s Great Divorce

The most significant change to the US map during Civil War history was the birth of West Virginia. It’s the only state to form by seceding from a Confederate state.

💡 You might also like: What Year Civil War Began: The Complicated Reality of 1861

The folks in the Appalachian mountains had nothing in common with the plantation owners in Richmond. They didn't own slaves, they didn't have the same economy, and they flat-out refused to fight for the South. In 1863, they officially broke away.

This was technically unconstitutional. The Constitution says you can't form a new state from an existing one without that state’s permission. But since the Union viewed Virginia's government as "illegal," they just pretended the pro-Union rump government in Wheeling was the real Virginia and gave themselves permission. It was legal gymnastics at its finest.

Mapping the Blockade

You can't talk about the map without talking about the water. The "Anaconda Plan" was the Union's strategy to wrap around the South like a snake.

If you look at a maritime US map during Civil War years, you’ll see the coastline dotted with Union Navy stations. From the Chesapeake Bay all the way down to Galveston, Texas, the North attempted to seal off the South from the rest of the world. This made the "map" of the South shrink every year. By 1864, the Confederacy was essentially an island, cut off from the sea and cut in half by the Union's control of the Mississippi River.

When Vicksburg fell in July 1863, the Trans-Mississippi Department (Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana) was basically chopped off. The map of the "Confederate States" was no longer a contiguous country. It was two struggling halves that couldn't talk to each other.

How to Read an Authentic 1860s Map

If you’re looking at an actual map printed in 1862, you'll notice things that feel "wrong."

🔗 Read more: Hit and run Delaware: What you actually need to do when the other driver bolts

- Indian Territory: There is no Oklahoma. It’s just "Indian Territory," and interestingly, many of the tribes there, like the Cherokee, actually signed treaties with the Confederacy.

- The "Unorganized" North: Huge swaths of the upper Midwest were still just dots and dashes.

- The Rail Lines: This is the most important part of any US map during Civil War study. The North had a dense, interconnected web of tracks. The South had a few main lines that didn't even use the same gauge (width) of track, meaning you couldn't just run a train from one end to the other without stopping to switch cars.

Maps back then were propaganda tools. Northern cartographers would often draw the Union territories in bright, bold colors to make the North look massive and inevitable. Southern maps would emphasize the vastness of their territory, trying to show that they were too big to be conquered.

The Practical Legacy of the 1860s Map

So, what do you do with this? If you're a history buff or just curious, don't just look at a modern map and imagine it divided. Go to the Library of Congress digital archives. Search for "Phelps & Watson’s Military Map of the United States." It’s one of the most accurate snapshots of the era.

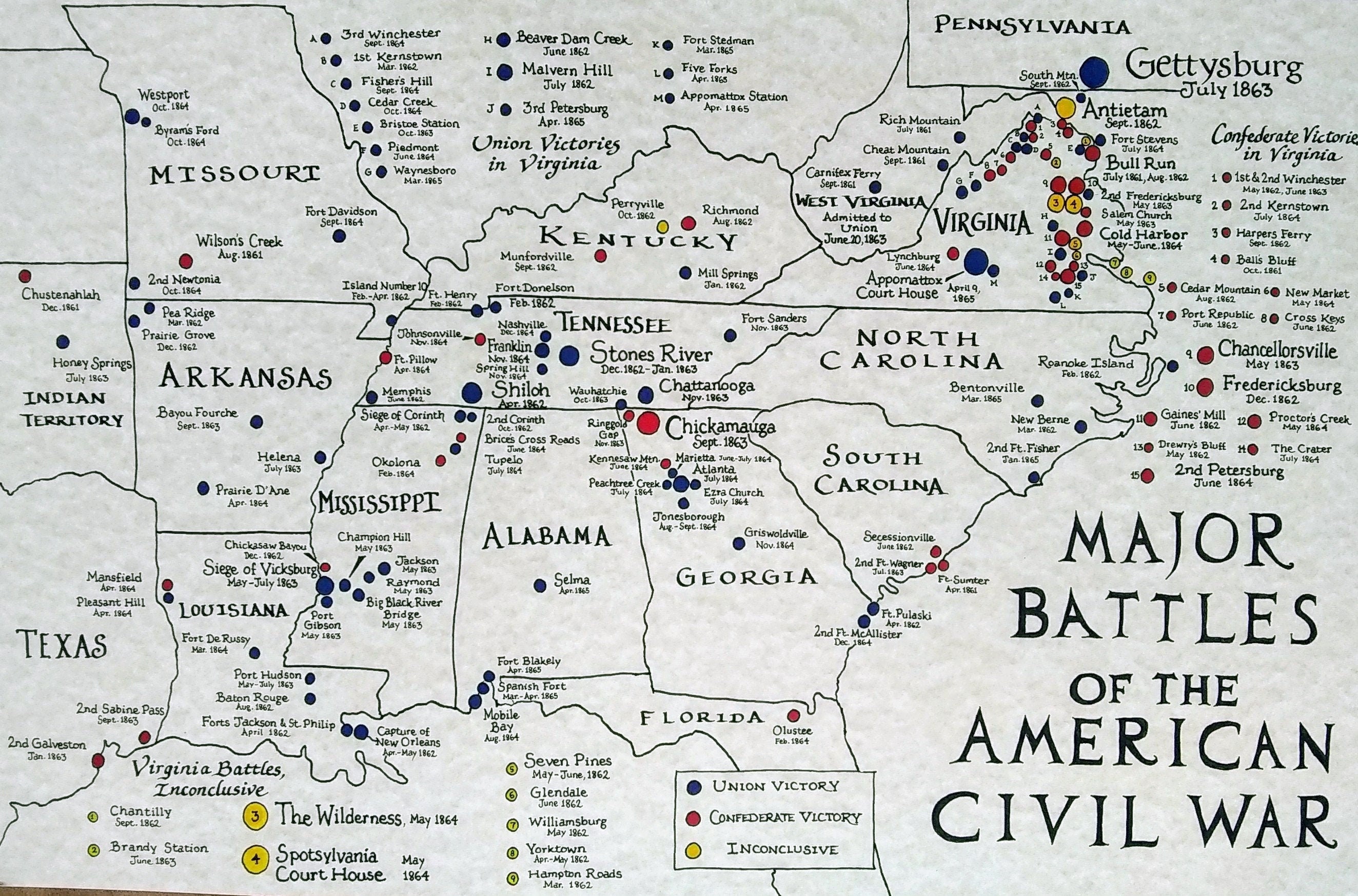

You'll see the "theaters of war." The Eastern Theater was tiny—just the space between Washington D.C. and Richmond. But the Western Theater was gargantuan.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts:

- Check the Date: A map from 1861 looks nothing like a map from 1863. If your map shows West Virginia but says 1861, it’s a reprint or a mistake.

- Look for the Railroads: The war was won on the tracks. Follow the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) railroad on a map to see why Maryland was so vital.

- Follow the Rivers: Note the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. These were the "backdoors" into the South that allowed the Union to bypass the heavy defenses on the Mississippi for years.

The US map during Civil War years wasn't just a guide for where things were. It was a blueprint for the country we have now. The borders of the West, the existence of West Virginia, and the central power of Washington D.C. were all forged in that five-year period of cartographic chaos.

To truly understand the conflict, you have to stop seeing the map as a finished product. See it as a work in progress. It was a sketch being redrawn every time a general moved a division or a surveyor found a new vein of silver in the desert. That’s the real story of the American map.

Next Steps for Deep Research

- Examine the "Great Map of the Rebellion": Use the David Rumsey Map Collection online to overlay 1860s maps with modern satellite imagery. It’s a trip to see where modern cities like Atlanta sit on top of old trench lines.

- Trace the "Slave Census" Maps: In 1861, the Coast Survey produced a map showing the density of the slave population. Lincoln supposedly spent hours studying it to see where the Union could find Southern allies (the "white patches" on the map).

- Visit National Battlefield Parks: Most have high-resolution topographic maps that show why the terrain—not just the state lines—dictated the outcome of the war.

- Study Territorial Evolution: Research the "Organic Acts" of the 1860s to see how Congress used the war to define the shapes of Idaho, Montana, and Arizona.

The borders we take for granted today were paid for in the 1860s. Every straight line in the West and every jagged river border in the East has a reason behind it, usually one involving a regiment of soldiers and a very tired surveyor.