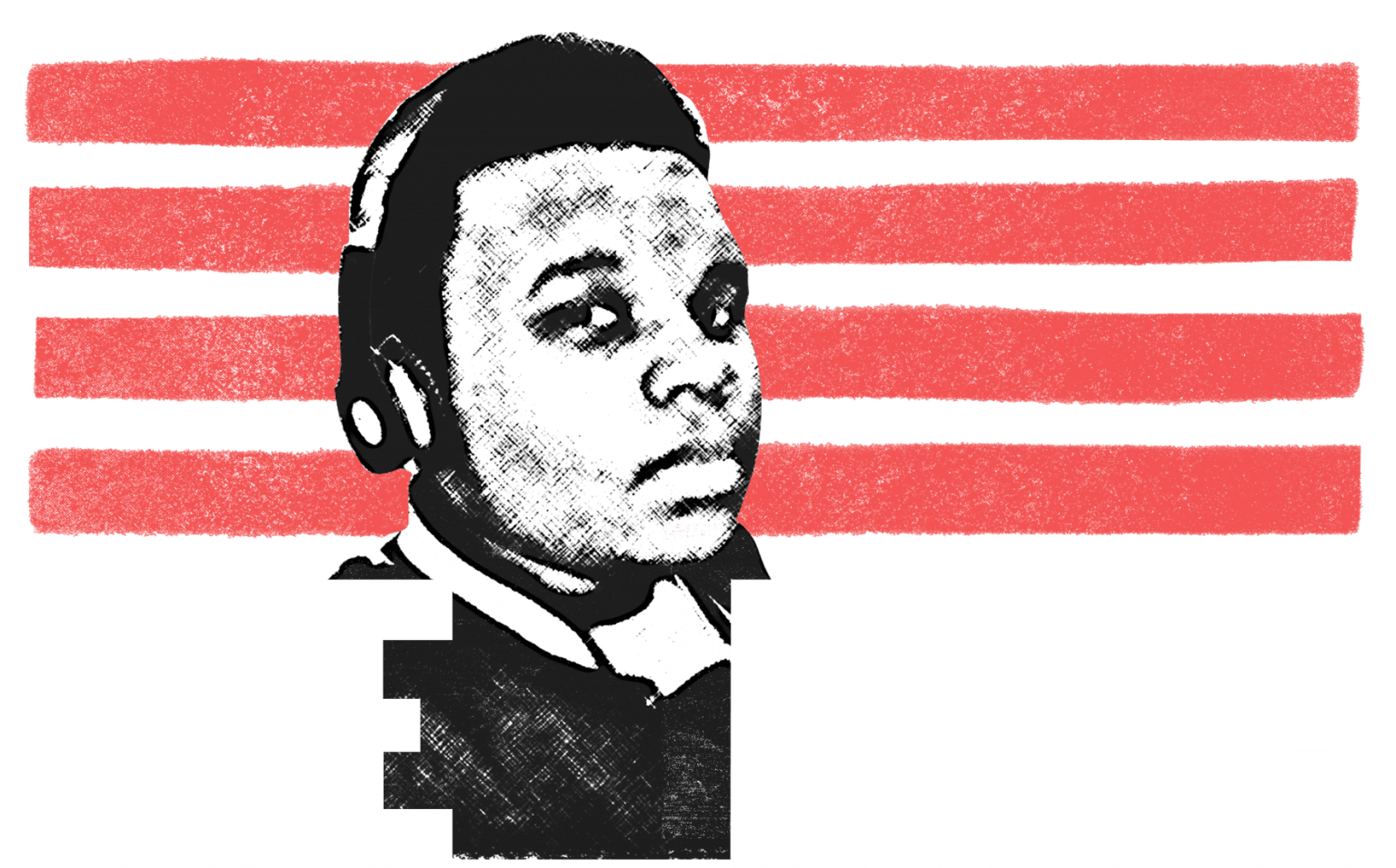

If you were paying any attention to the news back in the mid-2000s, specifically around 2005, you probably remember the name Michael Brown. But you might not remember the specific, grueling, and frankly disastrous weekend with Michael Brown that basically rewrote the handbook on how not to handle a national emergency. We’re talking about the former FEMA Director during Hurricane Katrina. It wasn't just a bad weekend for him; it was a catastrophic pivot point for American disaster response.

Most people think of Katrina as a singular moment of impact. It wasn't. It was a slow-motion car crash. And right at the center of that crash was "Brownie," the guy who famously got a "heck of a job" shoutout from President George W. Bush while the city of New Orleans was literally underwater.

Looking back, that specific window of time—that late August weekend—is a masterclass in what happens when bureaucratic ego meets a lack of preparation. It’s kinda wild to think about how much has changed since then. Or how much hasn't.

What actually happened during that weekend with Michael Brown?

Let's set the scene. It’s Saturday, August 27, 2005. Hurricane Katrina is churning in the Gulf. It's massive. It’s scary. Forecasters are screaming that this is "the big one."

Michael Brown is the head of FEMA. At this point, he’s already being warned by Max Mayfield, who was the Director of the National Hurricane Center. Mayfield was literally calling officials on their personal phones. He was terrified. But the vibe from FEMA that weekend? It was strangely detached.

By Sunday, the mandatory evacuation of New Orleans was finally called. But if you look at the logs and the subsequent congressional investigations—like the "A Failure of Initiative" report—the weekend with Michael Brown was defined by a massive disconnect between the federal government and the reality on the ground. Brown was reportedly focused on things that, in hindsight, seem almost trivial. There were emails about his attire. Emails about where he would eat. Meanwhile, the levees were about to fail.

The storm made landfall Monday morning. But the "weekend" is where the battle was lost.

You've got to understand the context of FEMA at the time. It had been folded into the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) after 9/11. This is a huge detail people miss. FEMA was no longer a cabinet-level agency. It was a sub-agency competing for scraps. Michael Brown, a former lawyer for the International Arabian Horse Association, was essentially a political appointee in a position that required deep, technical logistics expertise.

When the weekend hit, the lack of a "boots on the ground" mentality was glaring. Honestly, it felt like the federal government was waiting for a formal invitation to save people, while the people were already drowning.

The "Heck of a Job" moment and the fallout

Friday, September 2, 2005. That’s when the infamous quote happened. President Bush stood on the tarmac in Mobile, Alabama, and told Brown, "Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job."

At that exact moment, thousands of people were trapped at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center without food, water, or functional toilets. Brown had told the media just a day prior that the federal government didn't even know there were people at the convention center.

Think about that. The head of emergency management didn't know about thousands of refugees in a major American city for days.

The weekend with Michael Brown essentially became a shorthand for government incompetence. He resigned shortly after, on September 12. But the damage was done. The trust was broken.

What’s interesting, and something most people forget, is Brown’s defense later on. He claimed he was a scapegoat. He argued that the state and local officials—specifically Governor Kathleen Blanco and Mayor Ray Nagin—didn't provide the clear requests for help that the law required. There’s a grain of truth there; the coordination was a nightmare. But as the lead federal official, the buck stopped with him. He was the one with the satellite phones and the massive budget.

Why we’re still talking about this in 2026

You might wonder why a weekend from two decades ago still gets brought up in business schools and political science classes.

Basically, it’s because it defines the "Pre-Katrina" and "Post-Katrina" eras of emergency management. After that weekend with Michael Brown, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006. It gave FEMA back some of its teeth. It required the director to have actual experience in emergency management. Imagine that!

We see the shadows of that weekend every time a hurricane hits Florida or a wildfire tears through California. We look for the "Brownie" of the situation. We look for the official who seems more concerned with the optics of the briefing than the logistics of the water bottles.

The technical failures of that weekend:

- Communications breakdown: The internal FEMA emails showed a lack of urgency.

- Logistics stalling: Supplies were staged, but the "last mile" delivery was non-existent.

- Bureaucratic friction: The tension between DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff and Michael Brown caused a "dual-headed" command structure that confused everyone.

It’s easy to point fingers at one guy. And Brown certainly earned a lot of that criticism. But the weekend with Michael Brown was also a systemic failure. It showed what happens when you prioritize political loyalty over operational competence.

✨ Don't miss: Cost of Gold Per Gram: Why the Prices Are Breaking Every Rule in 2026

I remember reading the transcripts of his testimony before the House Select Bipartisan Committee. He was combative. He was defensive. He didn't seem to grasp the visceral horror of what people went through. That lack of empathy is perhaps the biggest takeaway for anyone in a leadership position. If you lose the human element, you've already lost the room.

Lessons learned (The hard way)

If you’re a business leader or someone involved in any kind of organizational planning, there are three massive takeaways from the Michael Brown era.

First, your "crisis mode" can't start when the crisis hits. It has to start days before. By the time Katrina made landfall on that Monday, the weekend with Michael Brown had already set the stage for failure because the "pre-landfall" staging was insufficient.

Second, communication isn't just about sending emails. It's about ensuring the message was received and understood. The "I didn't know about the convention center" excuse is the ultimate red flag. If your subordinates aren't telling you the worst news, you’ve created a culture of fear or incompetence.

Third, expertise matters. You can't "lawyer" your way through a Category 5 hurricane. You need people who understand supply chains, drainage, and human psychology.

Actionable Insights for Modern Crisis Management

- Audit your "Single Points of Failure": In 2005, the single point of failure was the lack of direct communication between the FEMA Director and the local commanders. In your world, find out where the "information silo" lives and break it before it breaks you.

- Prioritize "Active Intelligence": Don't wait for reports to come to you. Use every available tool—social media monitoring, direct field check-ins, and third-party data—to verify what's actually happening. Michael Brown relied on a chain of command that was already broken.

- The "Humanity First" Rule: If you are in a leadership position during a crisis, your first public appearance and your first internal memo must acknowledge the human cost. Failure to do so makes everything else you say feel like a lie.

- Practice Cross-Functional Drills: The friction between the city, state, and federal levels during that weekend was fatal. If you haven't run a "tabletop exercise" with your partners or vendors lately, do it now.

The weekend with Michael Brown remains a stark reminder that in a crisis, time is the only resource you can't buy back. Once those 48 hours before the "storm" are gone, they're gone forever. We saw it in 2005, and we see it in every major corporate or natural disaster today. The prep work is the work. Everything else is just reacting.

💡 You might also like: Credit Analysis and Research Limited Share Price: What the Market is Actually Thinking

Don't let your "weekend" be the reason everything falls apart. Build the systems now so that when the pressure mounts, the structure holds. That is the only real legacy worth leaving behind in emergency management.