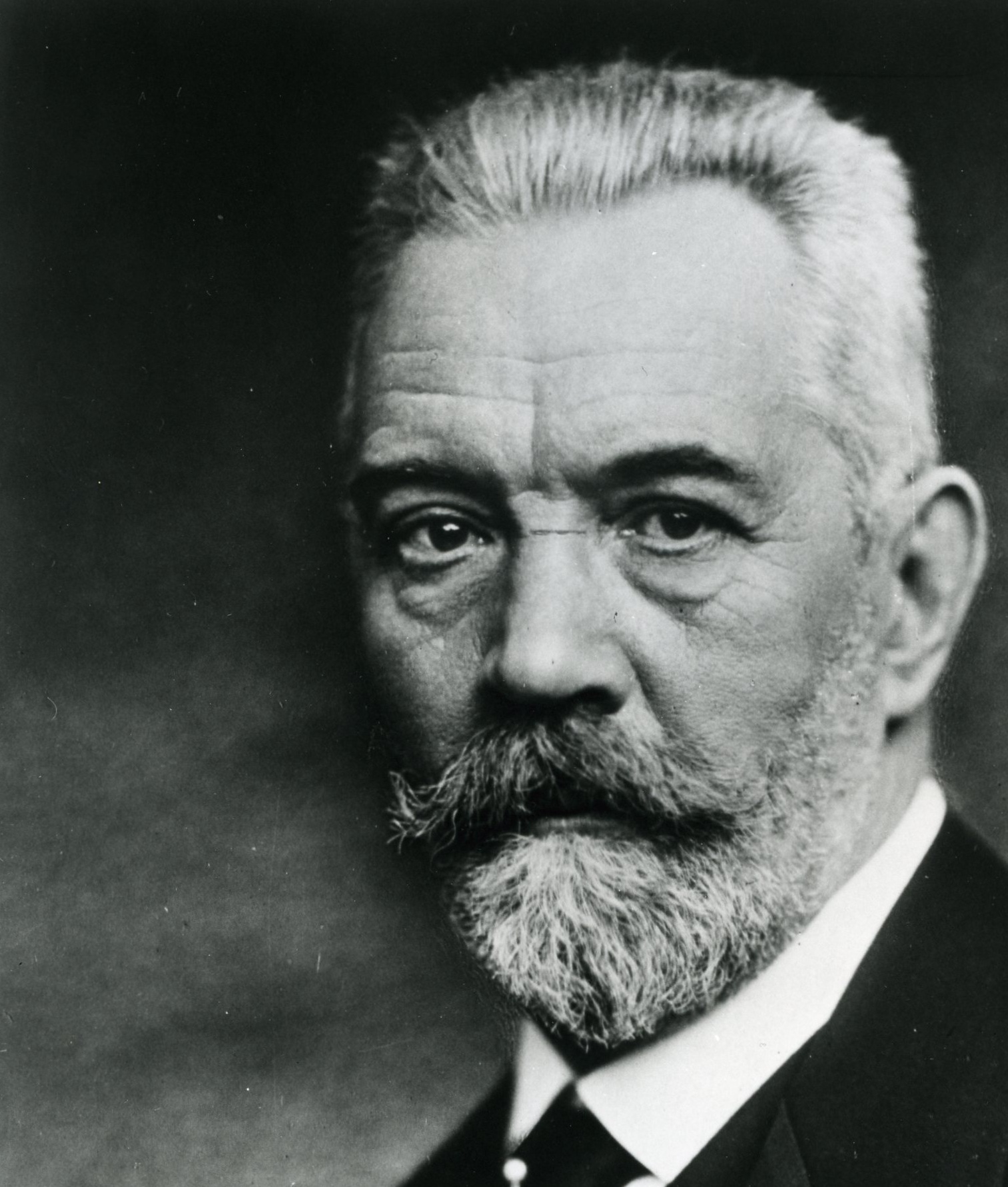

If you’ve ever deep-dived into the messy, tragic beginnings of World War I, you’ve probably seen the name Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg. Most history books treat him like a footnote. A guy in a high collar who couldn't stop a global catastrophe.

That’s a bit of a disservice. Honestly, his story is less about a boring bureaucrat and more about a man trapped in a burning building of his own design.

He was the fifth Chancellor of the German Empire. Serving from 1909 to 1917, he basically held the steering wheel during the most violent turn in modern history. People often call him "the Hamlet of German politics." It’s a fitting nickname. He spent his career second-guessing himself while the world around him screamed for blood.

The Man Who Tried to Thread the Needle

Bethmann Hollweg wasn't your typical saber-rattling Prussian. He came from a banking and academic background, not the old-school military aristocracy. This made him a bit of an outsider. He was cultured. He loved philosophy. He probably would have been much happier in a library than in the Reichstag.

Kaiser Wilhelm II liked him because he was "safe." Bethmann wasn't a firebrand like Bismarck. He tried to run what he called a "diagonal policy."

Basically, he wanted to walk a middle line. He tried to keep the angry Socialists on the left from revolting while keeping the ultra-conservative "Junkers" on the right from losing their minds. It was an impossible job. You’ve probably tried to please two different friend groups at a party; now imagine those friends have armies and want to overthrow the government.

- He pushed for a more liberal constitution for Alsace-Lorraine in 1911.

- He tried to reform the archaic "three-class" voting system in Prussia.

- He consistently tried to talk the British into a naval agreement to stop the arms race.

Most of these efforts failed. Why? Because he was constantly overruled by the military. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the guy obsessed with building giant battleships, hated him. The Kaiser, who was famously erratic, would back him one day and leave him to the wolves the next.

The July Crisis and the "Blank Check"

Here is where the history gets dark. In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. Most people think Germany just wanted a war and jumped at the chance. The reality for Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg was a lot more complicated—and a lot more desperate.

He believed Russia was becoming too powerful. He thought if Germany didn't act soon, they’d be crushed in a few years anyway. So, he helped issue the infamous "blank check" to Austria-Hungary. This was basically Germany saying, "Go ahead and deal with Serbia; we’ve got your back."

He gambled. Big time.

He thought he could keep the war "localized." He figured Russia would back down or that Britain would stay neutral. He was wrong on both counts.

👉 See also: Why the number of house seats has stayed at 435 for over a century

As the dominos started falling, Bethmann spiraled into a fatalistic depression. There’s a famous story of him sitting in his garden during the final days of July 1914. A friend asked him how he was. He supposedly said, "A leap into the dark, and a very heavy responsibility."

He knew.

The "Scrap of Paper" Gaffe

You might have heard the phrase "a scrap of paper." That was Bethmann’s biggest PR disaster. When Britain declared war because Germany invaded neutral Belgium, the British ambassador came to see him. Bethmann, exhausted and losing his cool, yelled that Britain was going to war over a "scrap of paper"—referring to the 1839 treaty that guaranteed Belgian neutrality.

It was a total disaster. The Allied propaganda machines ate it up. It made Germany look like a lawless bully, even though Bethmann actually felt terrible about the invasion. He even admitted in the Reichstag that the invasion was a "wrong" that they would have to "make good" later. The military commanders, obviously, were not thrilled with him saying that.

The September Program: Secret Ambitions?

For a long time, historians thought Bethmann was a moderate who just got swept up in the war. Then, in the 1960s, a historian named Fritz Fischer found a document called the September Program (1914).

This plan was wild. It outlined a Germany that basically owned all of Europe.

- Belgium would become a vassal state.

- Parts of France would be annexed.

- A massive economic union (Mitteleuropa) would be controlled by Berlin.

Does this mean Bethmann was a secret conqueror? It's debated. Some say he was just writing down what the military and industrial leaders wanted to hear so they wouldn't fire him. Others say it proves he wanted the war all along. Kinda depends on which historian you ask.

The Downfall of a "Hamlet"

By 1917, Bethmann Hollweg was a man without a country. The military, led by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, had basically taken over the government. They wanted "unrestricted submarine warfare"—sinking any ship, including American ones, to starve out Britain.

Bethmann fought it. He knew it would bring the United States into the war. He knew the U.S. would tip the scales and Germany would lose.

But he didn't have the spine to stop them. Or maybe he just didn't have the power. He eventually gave in. The U.S. joined the war, and his prophecy of doom came true.

The military finally got rid of him in July 1917. They found him too "weak" and too interested in a negotiated peace. He retired to his estate at Hohenfinow, watched the Empire collapse, and died in 1921.

💡 You might also like: President of the Senate Is the Vice President: Why This Dual Role Actually Matters

Why You Should Care Today

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg is a case study in what happens when "competent" bureaucrats try to manage a system that is fundamentally broken. He wasn't a monster. He was a man of high character who lacked the political "killer instinct" to stop the extremists in his own government.

Actionable Insights from Bethmann's Career:

- The Danger of "Calculated Risk": Bethmann thought he could control a crisis by escalating it just enough. It’s a reminder that once you start a fire, you don't get to choose which way the wind blows.

- The Cost of Silence: By not standing up more forcefully to the military elite (the OHL), he became an accomplice to the policies he knew would ruin his country.

- Context Matters: To understand 1914, you have to look at the domestic pressure. Bethmann was fighting a war at home against political rivals just as much as he was fighting a war abroad.

If you want to understand why Europe looks the way it does today, you have to look at the failure of the "diagonal policy." It was the last-ditch effort to save a world that was already ending.

To see how this shaped modern diplomacy, you might want to look into the Fischer Controversy or read Bethmann’s own memoirs, Reflections on the World War. They are surprisingly honest about the "guilt" he felt for the catastrophe.