It was 1997. People were skeptical. The production of Titanic by James Cameron was, by all accounts, a disaster in the making. It was way over budget. The release date kept getting pushed back. Everyone in Hollywood was whispering that it would be the biggest "sinker" in cinematic history, a vanity project that would bankrupt 20th Century Fox and Paramount.

But then it came out.

And it stayed in theaters for months. Literally months. You couldn't go anywhere without hearing Celine Dion’s flute intro or seeing teenage girls lining up for their eighth viewing. It wasn't just a movie; it was a cultural fever dream. Honestly, looking back, the sheer scale of what Cameron pulled off is kind of terrifying. He didn't just make a movie about a shipwreck; he rebuilt the ship, lived at the bottom of the Atlantic for a while, and forced the entire world to care about a fictional romance set against a very real tragedy.

The Obsessive Realism of James Cameron

If you want to understand why Titanic by James Cameron works, you have to look at the guy’s ego—in a good way. Cameron is a diver first and a filmmaker second. He’s visited the wreck of the RMS Titanic thirty-three times. That’s more time than the actual captain spent on the ship. This isn't just "research." It’s an obsession with the physical reality of the event.

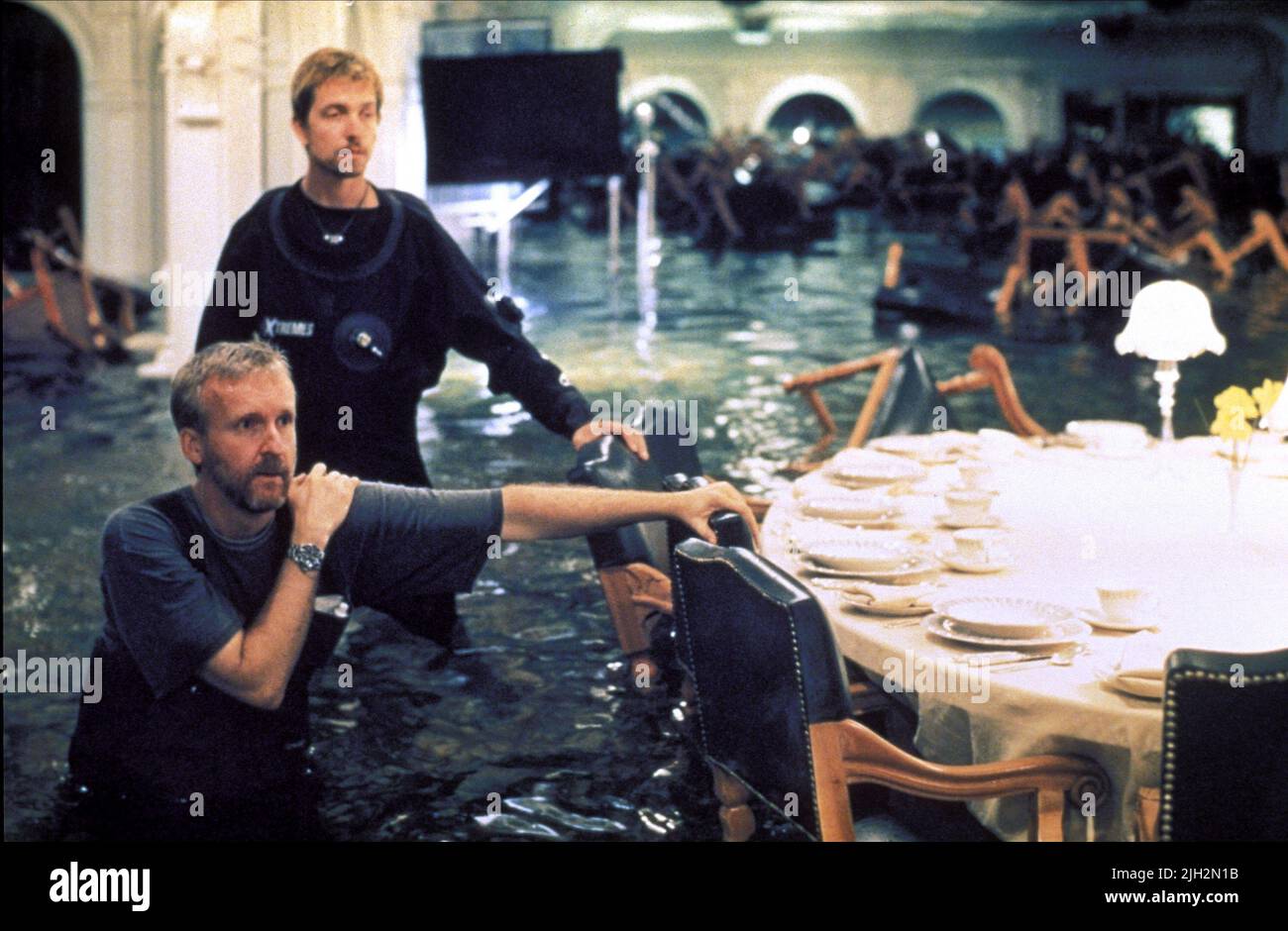

Most people don't realize that the "Big Set" in Rosarito, Mexico, was a 90% scale model of the actual ship. They didn't just build a facade; they built a 775-foot-long monster in a 17-million-gallon water tank. When you see the water crashing through the Grand Staircase, that wasn't a digital effect. That was actual ocean water destroying a meticulously handcrafted set. The actors were actually cold. The breath you see in the final scenes? That wasn't added in post-production. They filmed in a refrigerated set.

- The Carpeting: Cameron tracked down the original company, BMK Stoddard of Kidderminster, to recreate the exact patterns used in 1912.

- The Davits: The cranes used to lower the lifeboats were built by the same company that built the originals for the White Star Line.

- The Plates: Every piece of china carried the White Star logo.

It’s almost pathological. But that's the secret sauce. You feel the weight of the steel. When the ship snaps in half—a theory Cameron championed based on wreck analysis before it was widely accepted—it feels like a physical violation of physics.

Jack and Rose: The Lightning Rod for Criticism

Let’s talk about the "Rose could have shared the door" debate. It’s the internet's favorite argument. Even today, people pull out thermal maps and buoyancy calculations to prove Jack Dawson didn't have to die.

Honestly? It doesn't matter.

🔗 Read more: John Holmes and Traci Lords: What Most People Get Wrong

Titanic by James Cameron isn't a survival guide; it’s a tragedy. If Jack lives, the movie is a standard romance. If he dies, it’s a myth. Cameron has said a thousand times that Jack had to die because the movie is about loss. It’s about the fact that 1,500 people died, and you can’t represent that scale of grief without breaking the audience's heart.

The chemistry between Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet was lightning in a bottle. Before this, Leo was a "serious" indie actor from What’s Eating Gilbert Grape. After? He was the biggest star on the planet. Kate Winslet famously campaigned for the role, sending Cameron roses with a note saying "I'm your Rose." She knew. She saw the script and realized this wasn't just a blockbuster—it was a period piece with the soul of a blockbuster.

The Technical Wizardry and the "Digital" Revolution

While the physical sets were the stars, the CGI was groundbreaking for the late 90s. This was the era of The Phantom Menace and Jurassic Park, but Cameron used digital effects differently. He used them to populate the ship.

Digital Domain, the VFX house, created "digital actors" to walk the decks. If you look closely at the wide shots of the ship sailing, those aren't real people. They’re 1997-era pixels. Yet, because the lighting matched the physical model so perfectly, our brains didn't reject it. It set the stage for everything Cameron would do later with Avatar.

The sinking sequence itself is a masterclass in pacing. It takes over an hour. It’s agonizing. By the time the stern is standing vertical in the air, the audience is as exhausted as the characters. Most disaster movies rush the climax. Cameron slows it down. He makes you sit in the dark and watch the lights flicker out.

Misconceptions About the History

People often knock the movie for being "inaccurate" because of the Jack and Rose story. But the background details? They're almost flawless.

- The Band: They really did play until the end. While "Nearer, My God, to Thee" is the legend, some survivors claimed it was popular ragtime tunes. Cameron chose the legend because it fits the tone.

- The Officers: The portrayal of William Murdoch was controversial. His family in Scotland actually received an apology from the studio because the film showed him taking a bribe and shooting himself—things that aren't backed by definitive proof, though some survivor accounts mentioned a suicide.

- The "Unsinkable" Myth: The ship was never officially marketed as unsinkable by the White Star Line before the tragedy. That was largely a media narrative that grew after the sinking.

Why the Movie Still Ranks

Go to TikTok or Twitter today. You’ll still see clips of the "drawing scene" or the "I'm flying" moment. Titanic by James Cameron has a weirdly long tail. It's because it’s a "maximalist" film. Everything is turned up to eleven. The music, the sets, the stakes.

It’s also one of the few movies that bridges the gap between generations. Your grandmother likes it for the period costumes. Your younger brother likes it for the destruction. You like it for the sheer audacity of the filmmaking.

The 25th-anniversary 4K remaster proved there’s still a massive appetite for it. Seeing it in 3D HFR (High Frame Rate) was a polarizing experience, but it highlighted just how much detail Cameron packed into every frame. You can see the individual beads on Rose’s "jump" dress. You can see the rust on the rivets.

Moving Beyond the Hype

If you want to truly appreciate the film today, you have to look past the "King of the World" memes. Look at the editing. Look at how Conrad Buff and Richard A. Harris cut between the 1912 story and the 1996 "present day" discovery. It shouldn't work. It should feel clunky. Instead, it gives the tragedy a sense of "ghostly" weight. We aren't just watching a story; we're excavating a memory.

The film is a reminder of a time when we built things—both ships and movies—out of steel and sweat rather than just green screens.

What You Should Do Next

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Titanic by James Cameron, skip the "making of" fluff pieces and go straight to the source.

- Watch the 4K Remaster: The color grading is significantly different from the original DVD/VHS releases, closer to what Cameron intended.

- Read "Titanic: James Cameron's Illustrated Screenplay": It includes notes on scenes that were cut, including a much longer fight between Jack and Lovejoy in the sinking dining saloon.

- Check out the 20th Century Fox "Production Notes": These archives detail the logistical nightmare of the Rosarito tank, including the time the entire crew was accidentally poisoned with PCP-laced clam chowder (yes, that really happened).

- Visit a "Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition": Many of the items seen in the film, like the cherub from the staircase, have real-world counterparts on display in cities like Las Vegas or Orlando.

The legacy of the film isn't just the Oscars or the box office. It's the fact that when we think of the Titanic today, we don't think of black-and-white photos. We think in Cameron’s colors. We think of the blue of the "Heart of the Ocean" and the orange glow of the boiler rooms. He didn't just document history; he replaced our collective memory of it with his own vision. That’s the real power of cinema.