Politics gets weird. We've all seen the memes, the late-night sketches, and the endless Twitter threads that turn serious policy into playground insults. But one specific piece of political satire really stuck in the collective craw of the internet: Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown. It’s a rhyme that feels like it’s been around for a hundred years, yet it’s entirely a product of our modern, hyper-polarized digital age.

You’ve probably heard it. Or maybe you saw a cartoon version of it on a Facebook feed. It’s a riff on the classic Mother Goose nursery rhyme "Humpty Dumpty," but instead of a clumsy egg, the protagonist is a thinly veiled caricature of Donald Trump.

Satire is a survival mechanism. Honestly, when the news cycle feels like a Category 5 hurricane, people turn to humor to make sense of the wreckage. This specific rhyme didn't just appear out of thin air; it was part of a larger wave of "resistance" literature and art that surfaced during the 2016 and 2020 election cycles.

Where did "Trumpty Dumpty" actually come from?

It isn't just one guy in a basement. The phrase Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown has been used by various authors, illustrators, and random social media users. However, if you're looking for the "official" version, you have to look at the world of political parody books.

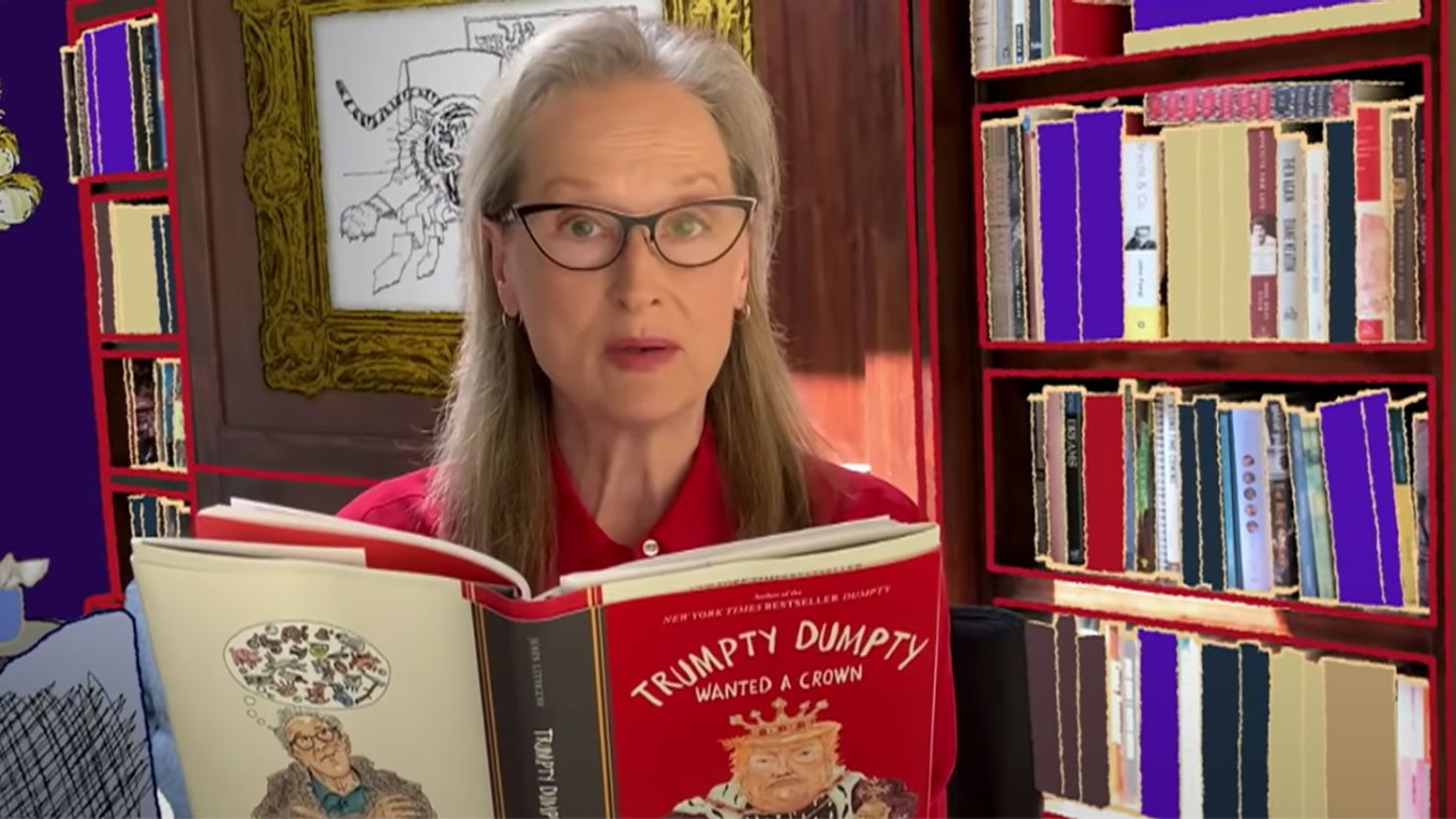

One of the most prominent examples is the book Trumpty Dumpty Wanted a Crown: Verses for a Despotic Age by John Lithgow. Yes, that John Lithgow. The Emmy-winning actor from 3rd Rock from the Sun and The Crown (ironically) turned his hand to political doggerel. Published in 2020, Lithgow’s book is a collection of poems that poke fun at the Trump administration.

Lithgow isn't a professional poet. He knows that. He’s admitted in several interviews, including talks with The New York Times and NPR, that he wrote these verses as a way to vent his own frustrations. He uses the structure of children's rhymes to highlight what he sees as the "childish" nature of modern political discourse. It’s a classic literary device: taking something innocent and making it biting.

But Lithgow wasn't the first. The "Trumpty Dumpty" moniker had been floating around political cartoons since 2015. Editorial cartoonists for major papers like The Washington Post and The Guardian often used the image of Trump as an egg on a wall to symbolize a fragile ego or an impending political "great fall."

✨ Don't miss: Why City of Stars Still Hits Different a Decade After La La Land

Why the "Crown" imagery matters so much

The rhyme says he "wanted a crown." That’s a very specific choice of words. In the context of American politics, a "crown" is the ultimate insult.

America was founded on the rejection of monarchy. Using the word "crown" suggests that a leader isn't interested in being a president, but rather a king. This was a central theme in the criticisms leveled against Trump by his opponents. They pointed to his rhetoric about executive power and his admiration for foreign strongmen as evidence of "monarchical" ambitions.

Basically, the rhyme is a shorthand for a much larger constitutional debate.

It’s about the "unitary executive theory." It’s about the limits of presidential immunity. When people shared the phrase Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown, they weren't just making a joke about a guy’s hair or his weight. They were expressing a deep-seated fear about the erosion of democratic norms.

The "wall" in the original Humpty Dumpty rhyme also took on a double meaning. In the original, the wall is just a prop. In the Trumpty version, the "wall" refers to the literal border wall between the U.S. and Mexico. The irony of an egg sitting on a wall that he himself insisted on building wasn't lost on the satirists.

The psychology of the political nursery rhyme

Why do we do this? Why do grown adults write nursery rhymes about the President of the United States?

It's about "reclaiming the narrative."

✨ Don't miss: Why Life Goes On Lyrics Still Hit Different Years Later

When you turn a powerful, intimidating figure into a silly character from a children's book, you strip away their power. You make them small. You make them manageable. Psychology calls this "diminishment." It’s a way for people who feel powerless to exert a tiny bit of control over their environment.

The simplicity of the rhyme is its greatest strength.

- It’s easy to remember.

- It’s easy to share.

- It fits perfectly on a protest sign.

- It bypasses complex policy debate and goes straight for the gut.

However, critics of this kind of satire argue that it’s reductive. They say that by turning serious political issues into "Trumpty Dumpty" jokes, we lose the ability to have nuanced conversations. If everything is a joke, nothing is serious. But honestly, in an era of "alternative facts," maybe a silly rhyme is the only thing that actually cuts through the noise.

The backlash and the "other side" of the wall

Of course, for every person who thinks Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown is a hilarious piece of commentary, there’s another person who thinks it’s "TDS" (Trump Derangement Syndrome) in poetic form.

Supporters of Donald Trump often view this kind of satire as elitist. They see Hollywood actors like Lithgow or editorial cartoonists as part of a "liberal establishment" that is out of touch with the average American. To them, the "crown" isn't a symbol of tyranny; it’s a symbol of a leader who finally puts America first.

Interestingly, the "Humpty Dumpty" metaphor has been flipped by the right as well. Some conservative commentators have used the "great fall" imagery to describe the "Deep State" or the mainstream media. It’s a tug-of-war over a fictional egg.

This brings us to a weird reality of 2026: even our nursery rhymes are polarized. You can tell a person’s political leanings just by which version of a 200-year-old rhyme they choose to recite.

Real-world impact: Does satire actually change anything?

Does a book by John Lithgow change votes? Probably not.

Most people who bought Trumpty Dumpty Wanted a Crown were already in the "anti-Trump" camp. Satire usually "preaches to the choir." It provides comfort and community to those who already agree with the message.

But it does serve a historical purpose. Satire acts as a time capsule. When historians look back at the early 21st century, they won't just look at census data or GDP growth. They’ll look at the memes. They’ll look at the political cartoons. They’ll look at Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown.

These artifacts show the emotional temperature of the country. They show what people were afraid of, what they hated, and what they found funny.

Take the "Kings of England" poems or the broadsides from the French Revolution. They were the "Trumpty Dumpty" of their day. They were crude, often unfair, and deeply partisan. But they were also the heartbeat of the political discourse.

Moving beyond the rhyme

If you’re interested in the intersection of politics and humor, don't stop at the memes. The "Trumpty Dumpty" phenomenon is just the tip of the iceberg.

To really understand how we got here, you have to look at the history of the First Amendment and the legal protections for parody. The landmark case Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) is a great place to start. The Supreme Court ruled that public figures can’t sue for "emotional distress" caused by satire unless they can prove "actual malice." This ruling is what allows books like Lithgow's to exist. Without it, political satire would be a very dangerous hobby.

Also, look at the work of Barry Blitt. He’s the guy who does those famous New Yorker covers. His style is much more subtle than a nursery rhyme, but it carries the same weight. He often uses the "clumsy leader" trope to great effect.

What you can do now

If you find yourself caught in the middle of a heated political debate, or if you're just exhausted by the constant back-and-forth, here are a few ways to process the "Trumpty Dumpty" era of politics:

- Check your sources. If you see a "Trumpty Dumpty" quote or poem online, verify who wrote it. Usually, it's a mix of John Lithgow’s work and anonymous internet "folk art."

- Study the history of satire. Read about Thomas Nast, the "Father of the American Cartoon." He basically invented the modern political image (including the GOP elephant). You'll see that the "Trumpty" jokes aren't new; they're part of a 150-year-old American tradition.

- Engage with the "other side's" humor. It’s uncomfortable, but looking at the memes and parodies created by people you disagree with can give you a lot of insight into their worldview. What are they making fun of? Why?

- Support local editorial cartoonists. Most local newspapers have cut their staff artists. These are the people who keep the "Trumpty Dumpty" tradition alive on a local level, holding mayors and city councils accountable with a pen and a pad.

The story of Trumpty Dumpty wanted a crown isn't just about a politician. It's about a country trying to find its voice in a noisy room. Whether you think it’s brilliant social commentary or just a mean-spirited joke, it’s a permanent part of our cultural record. It’s the sound of a democracy arguing with itself, one rhyme at a time.

Politics is heavy. Sometimes, the only way to carry it is to make it rhyme. If we can't laugh at the absurdity of a leader "wanting a crown" in a republic, then we've probably already lost the very thing we're trying to protect.

Don't let the simplicity of the verse fool you. Behind every silly drawing of an egg is a very serious question about power, ego, and the future of the United States. And that’s something no amount of "all the king's horses and all the king's men" can easily fix.

To explore this further, look up the original caricatures from the 1800s—you'll be shocked at how little has actually changed in the way we mock our leaders. The "crown" might be metaphorical now, but the battle for the "throne" is as real as ever. Stay curious, stay skeptical, and maybe keep a few rhymes in your back pocket for the next election cycle. You're going to need them.