You've probably seen that classic postcard of Tuscany. You know the one—perfectly symmetrical cypress trees lining a dusty road that snakes up to a terracotta villa. It’s beautiful, sure, but if you’re trying to understand a Tuscany wine region map, that image is actually kinda misleading. It makes everything look uniform.

Honestly? Tuscany is a mess. A glorious, hilly, geological mess.

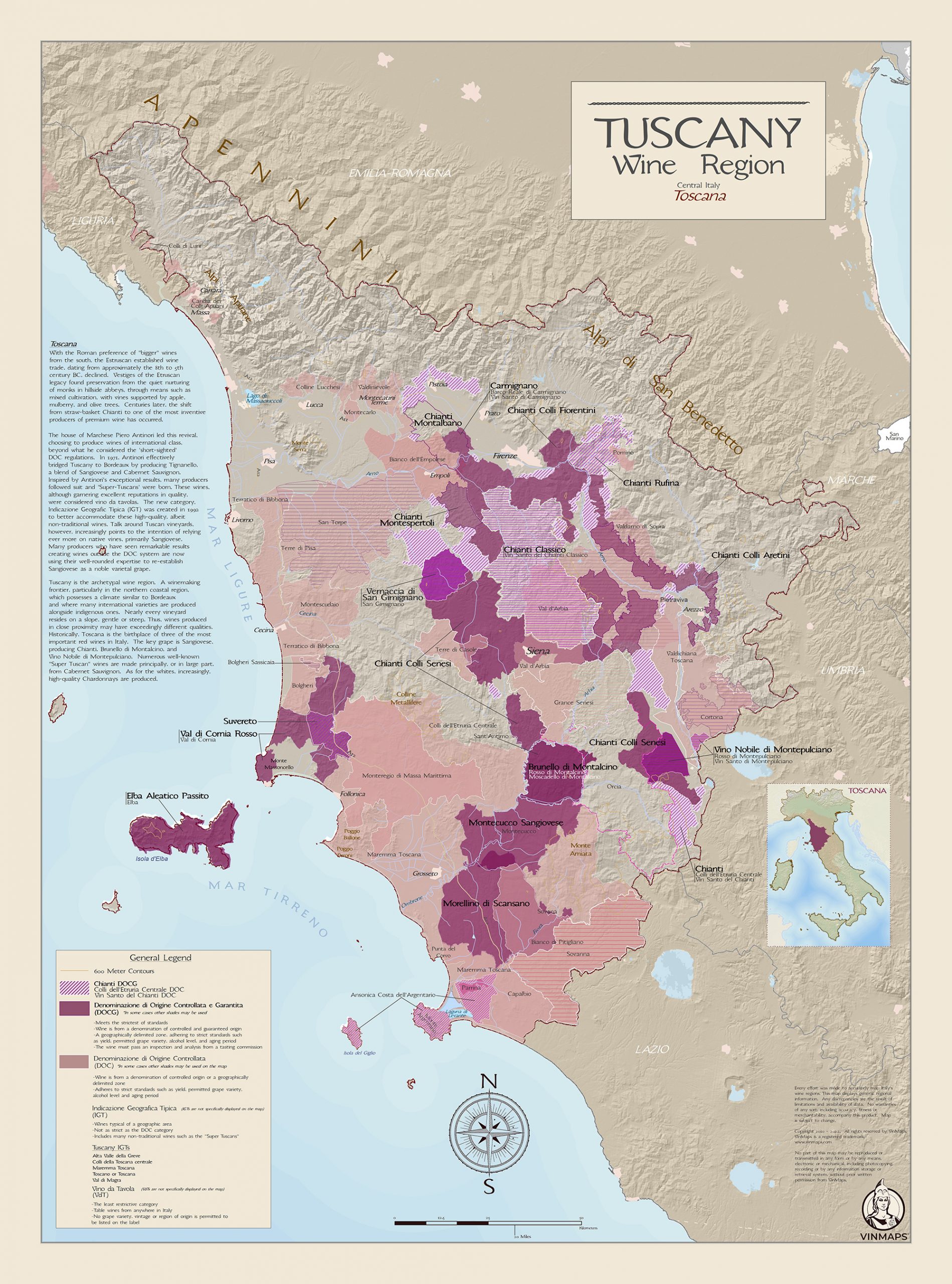

If you look at a map of the region today, you aren't just looking at "where the grapes grow." You’re looking at a centuries-old battle between tradition and some very modern red tape. From the salty breezes of the Maremma coast to the high-altitude limestone of Chianti Classico, the "borders" of these wines are shifting. In 2026, where a line is drawn on a map can be the difference between a $15 bottle of table wine and a $150 collector's item.

The Chianti Confusion: It's Not Just One Big Circle

Most people open a Tuscany wine region map and see a giant blob in the middle labeled "Chianti."

That’s the first mistake.

💡 You might also like: Slidell Mardi Gras 2025 Explained: What to Expect and Why It’s Not Just a New Orleans Side Note

There is Chianti, and then there is Chianti Classico. They aren't the same. Imagine Chianti as a massive umbrella. Underneath that umbrella, you have sub-zones like Chianti Rufina (the cool-climate underdog), Colli Senesi, and Chianti Montespertoli. But right in the heart—the "historic" core—sits Chianti Classico.

It even has its own separate map.

Back in 1716, the Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici drew the first official borders. He was basically the world's first wine regulator. Fast forward to now, and the Chianti Classico Consorzio has introduced something called UGAs (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive). These are eleven specific sub-regions within the Classico zone—names like Panzano, Gaiole, and Castelnuovo Berardenga.

Why does this matter to you? Because 2026 is the year these names are finally becoming common on labels. If you see "Greve" on a bottle, you're getting a different soil profile (mostly Macigno sandstone) than if you buy a bottle from the south, where the clay is heavier and the wine feels "warmer" and broader.

The Southern Powerhouses: Montalcino and Montepulciano

If you move your eyes south on the map, the hills get gentler, but the wines get way more intense.

Brunello di Montalcino

This is a small, square-ish blip on the map centered around the town of Montalcino. It’s arguably the most prestigious spot in Italy. What most people get wrong is thinking the whole "square" is equal. It’s not.

The northern slopes are higher and cooler. The wines there are like a laser—high acidity, elegant, floral. The southern slopes, closer to the Orcia River, get hammered by the sun. The grapes there get riper, leading to those "powerhouse" Brunellos that taste like dark chocolate and sun-baked earth.

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano

Just a short drive east from Montalcino is Montepulciano. Don't confuse it with the grape Montepulciano d'Abruzzo (different grape, different region). Here, they grow the Prugnolo Gentile, which is just a local nickname for Sangiovese.

The map here is also changing. As of 2025 and into 2026, they've started rolling out the "Pieve" system. They’ve mapped out 12 historical districts. If a winemaker uses the "Pieve" designation, the wine has to be at least 85% Sangiovese and come from a specific ancient parish boundary. It’s a move to stop being the "cheaper neighbor" to Brunello and show off their specific dirt.

The Wild West: Bolgheri and the Super Tuscans

Now, look at the left side of your Tuscany wine region map, right against the Tyrrhenian Sea. This is the Maremma.

Fifty years ago, this was mostly swampy marshland where people hunted wild boar. Today, it’s where the "Super Tuscans" live.

Bolgheri is the superstar here. Unlike the inland regions that obsess over Sangiovese, Bolgheri is all about the French varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc. The proximity to the sea creates a "mirror effect" with the sunlight reflecting off the water, helping the grapes ripen perfectly.

You’ve probably heard of Sassicaia or Ornellaia. These wines basically broke the old Italian wine laws because they didn't follow the "traditional" recipe. They were originally labeled as "table wine" because they weren't "proper" Italian wine. Eventually, the map had to catch up to the quality, and Bolgheri got its own DOC status.

The White Wine Outlier: San Gimignano

In a sea of red, there is one white island on the map.

San Gimignano is famous for its towers, but for wine nerds, it’s all about Vernaccia di San Gimignano. This was actually the very first wine in Italy to receive DOC status back in 1966. It’s a crisp, often salty white that grows in soil filled with crushed sea shells and prehistoric fossils.

If you’re looking at a map and feel overwhelmed by the red, just look for the little yellow dot near the center. That’s your palate cleanser.

How to Actually Use a Wine Map in 2026

Maps are great for orientation, but they don't tell the whole story of 2026.

The climate is getting warmer. That’s just a fact.

As a result, the "best" spots on the map are migrating uphill. Vineyards that were once considered "too high" or "too cold" in the 1980s are now the gold mines of Tuscany. Producers are buying land in the Appennine foothills—spots like the Mugello region north of Florence—where it’s cool enough to grow Pinot Nero or keep Sangiovese from becoming a "sugar bomb."

Also, look for the "IGT Toscana" label. Sometimes a winemaker has a brilliant vineyard that sits just ten feet outside a prestigious DOCG border. On the map, it looks like "no man's land." In the glass, it’s a bargain.

Your Next Steps for a Tuscan Wine Tour

If you're planning to visit or just want to buy better bottles, don't just look at the region name. Look at the producer and the specific village.

- Pick a "UGA" to explore. Start with Radda (cool, high altitude) versus Castelnuovo Berardenga (warm, southern) in Chianti Classico. The difference is wild.

- Seek out the "Pieve" wines. If you're into Montepulciano, look for those new labels coming out this year. They are the "cru" level of the region.

- Go coastal but skip Bolgheri. Look at the Suvereto or Val di Cornia sections of the map. You get that same Mediterranean sun for about a third of the price.

- Download a digital topographic map. A flat map is useless in Tuscany. You need to see the elevation. If a vineyard is below 200 meters, expect a riper, heavier wine. Above 400 meters? Expect elegance.

Tuscany isn't a static place. The map is a living document. The more you look at the jagged lines and the elevation marks, the more the wine in your glass starts to make sense. Grab a bottle of Chianti Rufina and see if you can "taste" the mountain air. That’s the real way to read a map.