Most people remember the unit circle as a colorful, intimidating wheel of numbers from high school trigonometry. You probably stared at those coordinates and wondered when, if ever, you’d actually use a reference angle in the real world. Honestly, it’s not just for passing a test. The unit circle degrees and radians system is basically the secret code behind every oscillating wave in your smartphone, the GPS in your car, and the way your favorite video game renders a sunset. Without this circle, the digital world simply stops spinning.

It’s just a circle with a radius of 1. That’s it. But that simplicity is deceptive. By locking the radius at a value of 1, mathematicians like Leonhard Euler—who basically paved the way for modern notation—realized they could turn geometry into a functional language.

The Tug-of-War Between Degrees and Radians

We grow up thinking in degrees. It feels natural. 360 degrees for a full circle, 90 for a right angle. It’s arbitrary, though. We use 360 because the ancient Babylonians liked the number 60, and 360 is roughly the number of days in a year. It’s a human invention, a "social construct" of mathematics.

Then you get to radians.

Radians aren't arbitrary. They are a measurement based on the circle itself. If you take the radius of a circle and wrap it along the edge (the arc), the angle you create is exactly one radian. Because the circumference of a circle is $2\pi r$, and our radius is 1, a full trip around the unit circle is $2\pi$ radians.

Engineering and physics favor radians because they make the calculus "cleaner." If you try to differentiate $sin(x)$ where $x$ is in degrees, you get a messy constant $(\frac{\pi}{180})$ tagging along like an annoying younger sibling. In radians? The derivative of $sin(x)$ is just $cos(x)$. It’s elegant. It works. This is why your scientific calculator has that "RAD/DEG" toggle that has likely ruined at least one of your exams.

Why the Unit Circle is Actually a Map

Think of the unit circle as a machine that converts "how far you’ve turned" into "where you are."

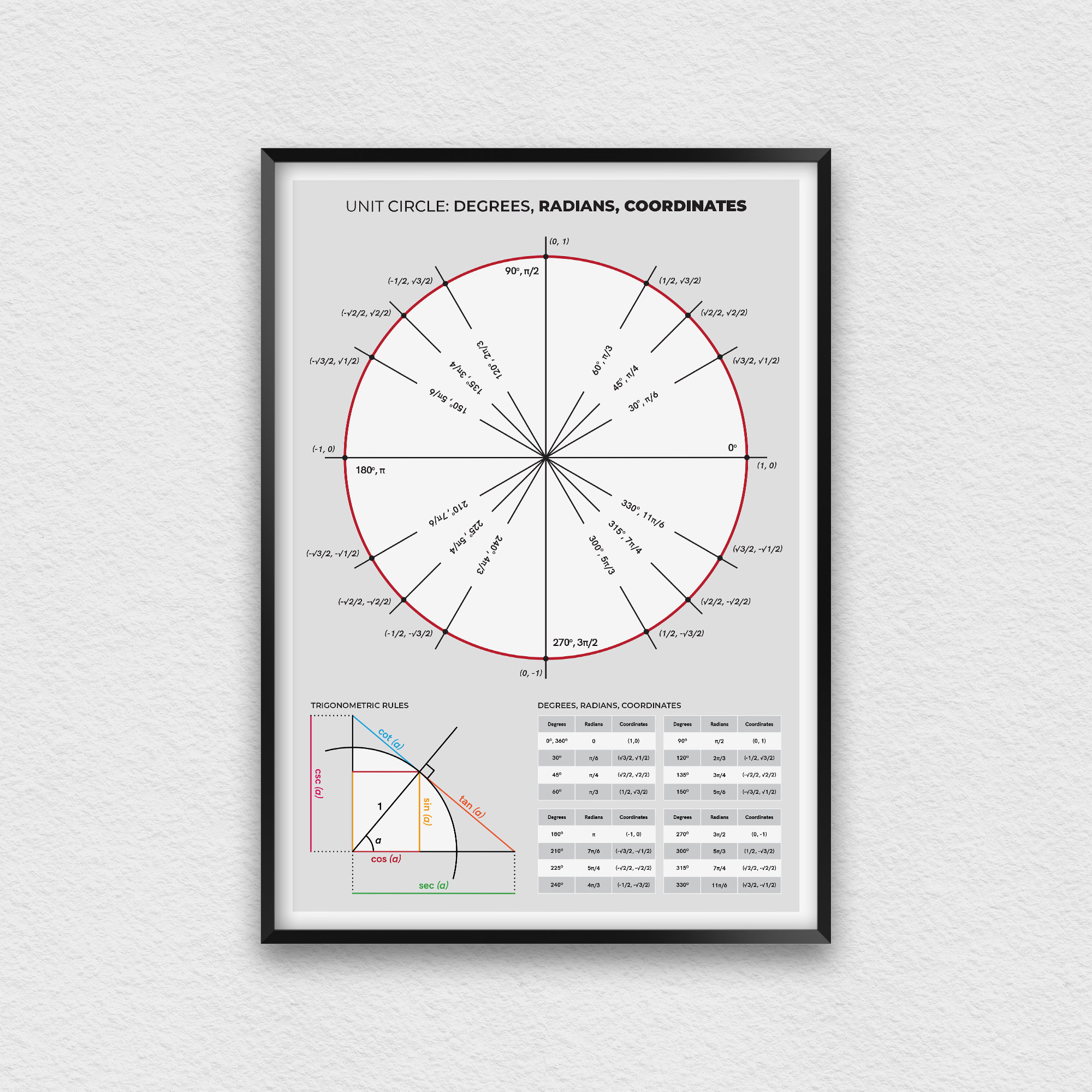

Every point on the circle is defined by $(cos \theta, sin \theta)$. If you’re at 90 degrees (or $\frac{\pi}{2}$ radians), you’re at the very top of the circle. Your horizontal position is 0, and your vertical position is 1. Hence, $(0, 1)$.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Amazon Kindle 6 Case Without Losing Your Mind

But what about those weird values like $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$?

Those come from special right triangles—the 30-60-90 and the 45-45-90. When you drop a vertical line from any point on the circle to the x-axis, you create a triangle. Because the hypotenuse is always 1 (our radius), the legs of that triangle are simply the sine and cosine values. This is where the magic happens for things like signal processing.

The Special Angles You Actually Need to Know

You don't need to memorize the whole thing, but you've gotta know the landmarks.

- 0° or 0 radians: The starting line. Coordinates: (1, 0).

- 30° or $\pi/6$: A shallow climb. Coordinates: $(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2})$.

- 45° or $\pi/4$: Perfect diagonal. The coordinates are twins: $(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}, \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})$.

- 60° or $\pi/3$: Steeper now. Coordinates: $(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})$.

- 90° or $\pi/2$: Straight up. Coordinates: (0, 1).

Notice a pattern? As the angle grows, the x-value (cosine) shrinks while the y-value (sine) grows. It’s a literal trade-off of horizontal space for vertical height.

The "All Students Take Calculus" Myth

Teachers use the acronym ASTC to help students remember which trigonometric functions are positive in which quadrant.

- Quadrant I (All): Everything is positive.

- Quadrant II (Students/Sine): Only sine is positive.

- Quadrant III (Take/Tangent): Only tangent is positive.

- Quadrant IV (Calculus/Cosine): Only cosine is positive.

It's a handy trick, but it’s better to just look at the axes. In Quadrant II, you’re on the left side of the graph (negative x) but still above the middle (positive y). Since cosine is x and sine is y, it makes sense that cosine is negative and sine is positive. Don't memorize the rule; just visualize the location.

Real-World Impact: From Spotify to Space

You might think unit circle degrees and radians are confined to textbooks. You’d be wrong.

Take digital audio. Sound is a wave. When you listen to a song on Spotify, your phone is essentially calculating sine and cosine waves at incredible speeds to reconstruct that audio signal. This uses something called a Fourier Transform, which is deeply rooted in the rotational logic of the unit circle.

In game development, if a character needs to walk at an angle, the engine uses the unit circle to figure out how much "forward" and how much "side-to-side" movement to apply. If the game didn't use these ratios, the character would actually move faster when walking diagonally than when walking straight—a common bug in early 8-bit games.

NASA uses these calculations for orbital mechanics. When a satellite orbits Earth, its position is a function of time and angle. Using radians allows engineers to relate the satellite's linear speed to its angular velocity effortlessly.

Converting Between the Two (The Fast Way)

Sometimes you're stuck with degrees but the formula demands radians. Or vice versa. You don't need a fancy converter. Just remember the "Bridge."

The Bridge is: $180^\circ = \pi \text{ radians}$.

If you want to get to radians, multiply by $\frac{\pi}{180}$. If you want to get back to degrees, multiply by $\frac{180}{\pi}$.

Example: You have 60°. Multiply by $\pi$ and divide by 180. $60/180$ simplifies to $1/3$. Boom. $\frac{\pi}{3}$.

It’s basic fraction work.

Common Pitfalls and Why They Happen

The biggest mistake? Mixing up the coordinates for 30° and 60°.

Think about it visually. At 30°, the point is further to the right than it is high. So the x-value must be the "big" number $(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \approx 0.866)$ and the y-value must be the "small" number $(0.5)$. At 60°, the opposite is true.

Another one is the "negative angle" trap. If a problem asks for $-30^\circ$, don't panic. Just go clockwise instead of counter-clockwise. $-30^\circ$ is the same spot as $330^\circ$. They are "coterminal."

A Different Perspective: The Tau Debate

There is a small but vocal group of mathematicians (like Michael Hartl) who argue that $\pi$ is actually the "wrong" number to focus on. They advocate for $\tau$ (Tau), which is equal to $2\pi$ (roughly 6.28).

The argument is that a full circle should be 1 unit of the circle's constant. With Tau, 1/4 of a circle is $\frac{\tau}{4}$, and a full circle is just $\tau$. It makes the unit circle degrees and radians relationship much more intuitive for beginners. While $\pi$ remains the standard, understanding that $2\pi$ represents one full rotation is the key to mastering the system.

Actionable Insights for Mastering the Circle

Stop trying to memorize the table of values. It’s a waste of brainpower. Instead, do this:

- Sketch the circle manually. Draw it five times. Mark the 0, 90, 180, and 270 points first.

- Internalize the triangles. Learn the two special triangles ($45-45-90$ and $30-60-90$). If you know those, you can derive any coordinate on the circle in seconds.

- Think in fractions of $\pi$. Instead of seeing $210^\circ$, see it as $180^\circ + 30^\circ$, which is $\pi + \frac{\pi}{6}$. That’s $\frac{7\pi}{6}$.

- Use the Hand Trick. There’s a famous "left-hand rule" for trig values where your fingers represent the standard angles. It's a great backup for when your brain freezes during a presentation or exam.

- Check your calculator mode. Before any calculation, verify if you are in DEG or RAD. This is the #1 cause of "wrong" answers in engineering and physics.

The unit circle isn't just a math requirement. It's a bridge between the physical world of rotation and the digital world of data. Once you stop seeing it as a list of numbers and start seeing it as a map of motion, the whole thing clicks. Keep practicing the conversions, and soon, you'll be visualizing these angles without even trying.