Most guys in the gym are just waving their arms around and hoping for the best. You see it every Monday. They stand between the cable towers, grab the handles, and perform what looks like a frantic bird flapping its wings to stay airborne. If you want that "shelf" look—the kind of upper pec development that pops out of a t-shirt—you need to stop treating upper chest cable flys like a casual accessory movement.

It's about the clavicular head. That’s the technical name for the upper portion of your pectoralis major. Unlike the sternocostal head (the big middle part), those upper fibers run at a specific upward diagonal angle from your collarbone down to your arm. If your cable path doesn't match that exact line, you're basically just giving your front delts a workout while your chest stays flat.

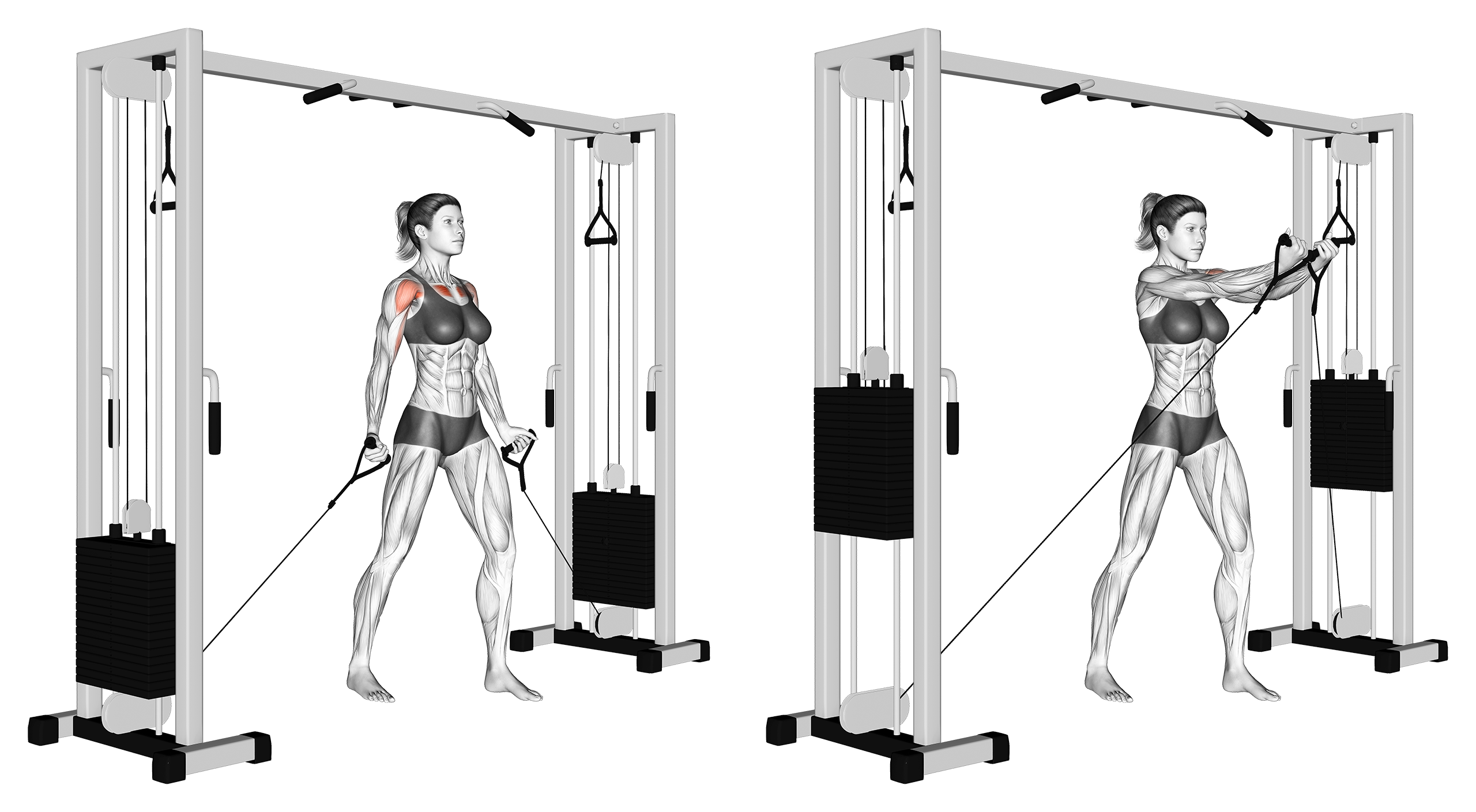

Honestly, the biggest mistake is the setup. People think "upper chest" and they immediately set the pulleys at the very top and pull downward. Stop. That is a lower chest move. To hit the top, you have to move from low to high.

👉 See also: How to Climax Faster Female: Why Speed Isn't Always About the Finish Line

The Physics of the Perfect Fly

Think about the way your muscle fibers are actually laid out. Science tells us that muscles pull in a straight line between their origin and insertion. For the upper chest, the origin is that medial half of your clavicle. To actually recruit those fibers, your arm has to travel across your body and up toward your chin.

If you set the cables at the bottom—right near the floor—and fly upward, you are creating a line of force that opposes those clavicular fibers. Dr. Mike Israetel from Renaissance Periodization often talks about "stimulus to fatigue ratio." You want the most bang for your buck. If you’re feeling it more in your neck or the very front of your shoulder, your pulleys are likely too low or your hands are traveling too far forward instead of up and in.

The sweet spot for most people is setting the pulleys at about hip height or slightly lower. From there, you aren't just hugging a tree. You are driving your biceps toward your nose. That's the secret. Don't think about your hands. Your hands are just hooks. Think about your elbows and your biceps. If you can get your biceps to touch the sides of your upper chest at the peak of the contraction, you've won.

Stop Overstretching the Shoulder Joint

There is this obsession with "the deep stretch." We've been told for decades that more range of motion equals more growth. While there is truth to the "stretched-mediated hypertrophy" research—studies like those from Pedrosa et al. (2023) suggest long muscle lengths are great for growth—there is a limit.

On a cable machine, the tension is constant. Unlike dumbbells, where the weight gets "light" at the bottom because of gravity, cables keep pulling on you. If you let your arms go too far back behind your torso, you stop stretching the chest and start overstretching the subscapularis and the anterior shoulder capsule. That's how you end up with a labrum tear.

Keep a slight bend in the elbows. Not a 90-degree bend—that's a press—but a soft curve. When you reach the back of the movement, your elbows should stay in line with your torso or just an inch behind it. If you feel a "sharp" pinch, you’ve gone too far. Retract your scapula. Keep your shoulder blades pinned against an imaginary wall. This creates a stable platform for the pec to pull against. Without that stability, your shoulders will roll forward, and the upper chest cable flys become a messy, ineffective shrug.

Why Cables Beat Dumbbells Every Single Day

Dumbbell flys are kind of a waste of time for the upper chest. Think about the physics. At the top of a dumbbell fly, when your hands are directly over your face, there is zero tension on the chest. Gravity is pulling the weight straight down through your bones. You could stand there all day.

Cables don't care about gravity. They care about the direction of the wire. Because the cable is pulling your arms out even when they are together, your upper chest has to stay contracted the entire time. This constant tension is what leads to metabolic stress, one of the primary drivers of muscle growth alongside mechanical tension.

Small Tweaks for Massive Recruitment

- The "Pinkies Up" Myth: Some people swear by rotating their wrists. Honestly? It doesn't do much for the chest. The chest doesn't attach to your forearm. It attaches to your humerus (upper arm). Focus on the angle of your upper arm, not which way your palms are facing.

- Staggered Stance vs. Square: Stand with one foot forward. It's not about the chest; it's about not falling over. A staggered stance lets you lean slightly into the movement, which helps you stabilize your core so you can move heavier weight without your torso swaying like a palm tree in a hurricane.

- The Cross-Over: Don't just bring your hands together. Cross them over. Since the pec’s job is horizontal adduction, crossing your hands allows the muscle to shorten even further. Switch which hand is on top every set to keep things symmetrical.

The Problem with "Heavy" Weights

This is an isolation move. If you're using the entire stack and your whole body is jerking forward to move the weight, you’re just ego lifting. The upper chest is a relatively small muscle group compared to the mid-chest and lats. It cannot move mountains.

💡 You might also like: Low Sodium Chicken Breast Recipes: Why Your Salt-Free Meals Taste Boring and How to Fix It

When you go too heavy, your body recruits the triceps, the front delts, and even your abs to "crunch" the weight up. You'll finish the set feeling tired, but your chest won't have that deep, burning pump. Drop the weight by 20%. Slow down the eccentric (the way back). Take three full seconds to open your arms. Pause at the bottom. Then, explode up and squeeze for a full second at the top.

If you can't hold the squeeze at the top for a "one-Mississippi" count, the weight is too heavy. Period.

Integrating Upper Chest Cable Flys into Your Split

You shouldn't lead with this. Your heavy hitters should always be compound movements—incline barbell press, weighted dips, or heavy dumbbell presses. Those are for mechanical tension. Use the upper chest cable flys as a "finisher" or a secondary movement.

A solid approach is doing 3 sets of 12-15 reps. High volume works well here because the cables allow for such a peak contraction. If you're doing a Push/Pull/Legs split, toss these in at the end of your push day when your shoulders are already warm.

Some lifters prefer "pre-exhaustion," where they do the flys first to tire out the chest before moving to a press. This ensures the chest fails before the triceps do. It’s a valid strategy, but generally, for pure hypertrophy, save the isolation for the end so you don't compromise your strength on the big lifts.

Common Obstacles and Variations

Sometimes the cable machine is crowded. If you can't get two pulleys, you can do these one arm at a time. It actually allows for a better range of motion because you can really twist your torso into the contraction.

Also, watch your height. If you're shorter, hip-height on the machine might be too high. If you're a giant, it might be too low. You want the cable to be roughly parallel to your forearm when you're in the starting "stretched" position. If the cable is rubbing against your biceps or shoulders during the rep, your pulley height is wrong. Adjust it until the path is clear.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Chest Workout

To fix your upper chest development starting today, follow this exact sequence:

- Set the Pulleys Right: Move the sliders to roughly waist height. This creates the necessary low-to-high diagonal path.

- Step Out and Stabilize: Grab the handles and take two big steps forward. Use a staggered stance (one foot in front of the other) and lean your torso forward about 15 degrees.

- The Path of the Bicep: Open your arms with a slight elbow bend. Stop when your elbows are even with your ribcage.

- Drive to the Nose: Sweep your arms upward and inward. Aim to bring your biceps together in front of your chin/nose area.

- The Peak Squeeze: Cross your wrists at the top. Contract your chest as hard as possible for one second.

- The Controlled Reset: Take three seconds to return to the starting position. Do not let the weight "clink" on the stack.

Consistency with this specific form will do more for your upper pec thickness in six weeks than six months of "heavy" ego-driven pressing. Focus on the feel, ignore the numbers on the stack, and let the mechanical tension do the work.