You’ve probably seen it. That terrifying, vertical red line on a U.S. debt history graph that makes it look like the entire American economy is about to fall off a jagged cliff. It’s the kind of chart that gets passed around on social media to spark a panic. But if you actually sit down and stare at the data—honestly stare at it—the story isn't just about "spending too much." It’s a messy, multi-century saga of wars, global pandemics, and shifting economic theories that most people completely gloss over.

Numbers don't lie, but they do hide things.

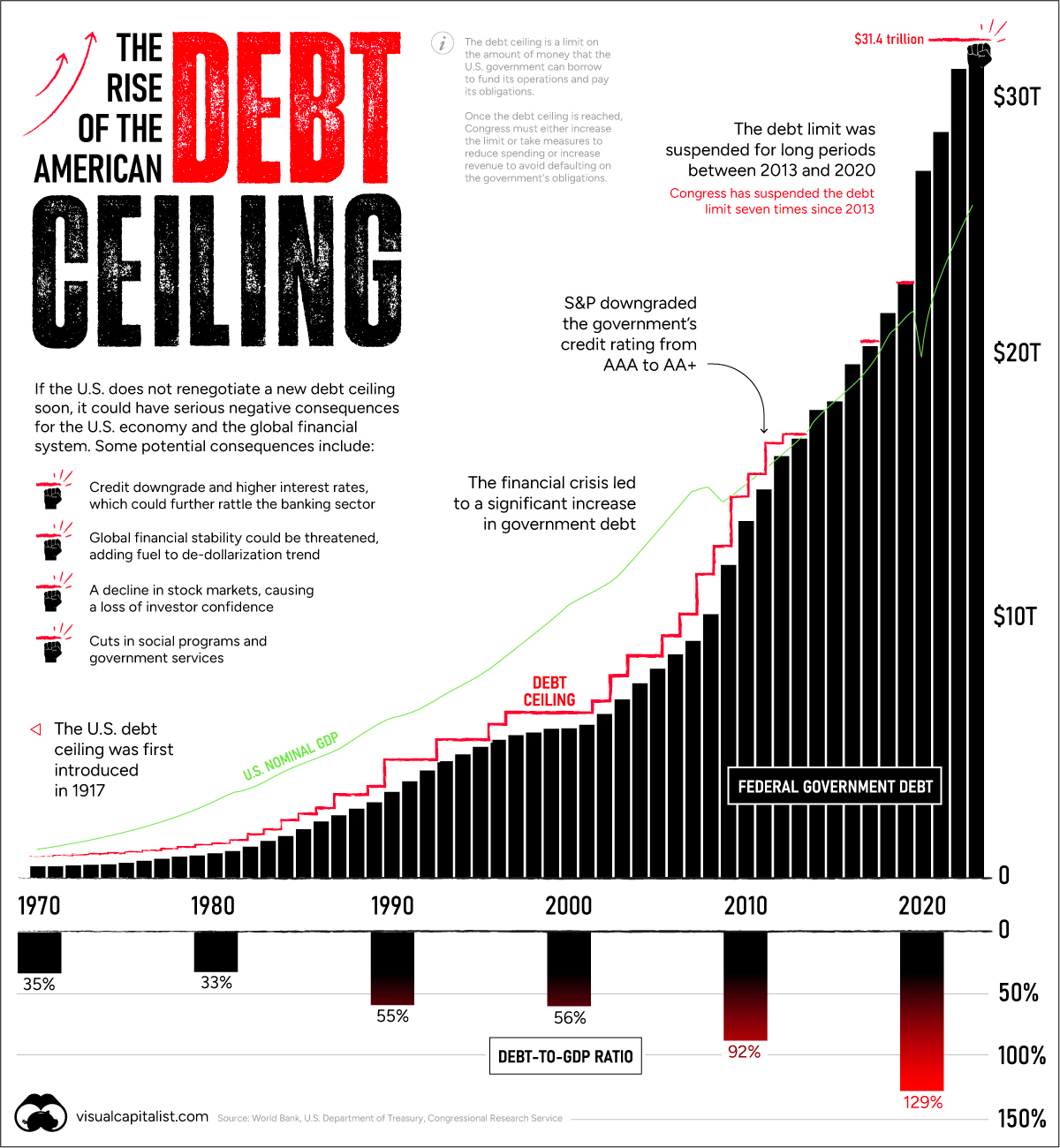

If you look at the raw nominal dollar amount, the graph looks like a rocket ship. We hit $34 trillion in early 2024 and kept climbing. However, any economist worth their salt will tell you that looking at a U.S. debt history graph in "nominal dollars" is basically useless for long-term planning. It’s like comparing the price of a gallon of milk in 1920 to one today without mentioning that Grandpa only made five cents an hour. To understand if we're actually in trouble, you have to look at debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

📖 Related: Wockhardt Ltd Share Price: Why Most Investors Are Missing the Real Story

That changes everything.

The Rollercoaster: Breaking Down the U.S. Debt History Graph

Most people assume the debt has always just gone up. Nope. For a huge chunk of American history, we were actually pretty good at paying things off. After the Revolutionary War, Alexander Hamilton—the guy on the ten-dollar bill—famously argued that a national debt could be a "national blessing" if it wasn't excessive. He wanted the federal government to assume state debts to build credit. It worked. By 1835, under Andrew Jackson, the national debt was actually zero. Zero! That was the first and only time that ever happened.

Then came the Civil War.

The U.S. debt history graph spikes hard in the 1860s. Wars are expensive. You can't run a continental conflict on pocket change. The debt jumped from roughly $65 million to $2.7 billion in just a few years. But here’s the kicker: we spent the next several decades aggressively paying it down. By the eve of World War I, the debt was back down to manageable levels. This "spike and retreat" pattern was the standard operating procedure for the U.S. Treasury for over a century.

Then the 20th century hit us like a freight train.

World War I caused another jump, but the real monster on the chart is World War II. If you look at a graph of debt-to-GDP, 1946 is the all-time peak before the modern era. We hit 106%. The entire country was essentially a war machine, and we borrowed every cent needed to win. But look at what happened next. Between 1946 and 1974, that percentage plummeted. We didn't necessarily pay off the debt in total dollars, but the economy grew so fast that the debt became "smaller" relative to our income. It’s like having a $1,000 credit card balance when you make $20k a year versus when you make $100k. The burden changes.

Why the Graph Changed Direction in the 1980s

Something shifted around 1981. If you’re looking at a U.S. debt history graph today, you’ll notice that the steady decline of the post-WWII era just... stops. Then it reverses.

Why?

✨ Don't miss: Why Females on Shark Tank are Actually Reshaping the Venture Capital Playbook

It was a "perfect storm" of policy changes. We had the Reagan-era tax cuts combined with a massive increase in military spending during the Cold War. Economists call this "structural deficits." For the first time, we started running large deficits during peacetime and periods of economic expansion. Usually, you borrow when things are bad and pay it back when things are good. In the 80s, we just kept borrowing.

There was a brief moment of sanity in the late 1990s. You might remember the "surplus" years under Bill Clinton. For a second there, the line on the graph actually dipped. There were even serious discussions among officials at the Federal Reserve about what would happen if the U.S. paid off all its debt—would the bond market collapse? It sounds like science fiction now.

Then 2001 happened.

- The Dot-com bubble burst.

- The September 11 attacks led to two incredibly expensive wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

- The 2001 and 2003 tax cuts reduced federal revenue significantly.

The graph didn't just go up; it accelerated.

The Modern "Hockey Stick" Effect

The Great Recession of 2008 was the next major catalyst. When the housing market imploded, tax tax revenue evaporated while government spending on safety nets and bank bailouts skyrocketed. The debt-to-GDP ratio jumped from about 62% in 2007 to over 90% by 2010.

And then came COVID-19.

If the previous years were a climb, 2020 was a teleportation to a new height. The government pumped trillions into the economy to prevent a total collapse. Stimulus checks, PPP loans, enhanced unemployment—it all showed up on the U.S. debt history graph as a near-vertical line. We blew past the World War II record of 106% debt-to-GDP.

Today, we are in uncharted waters.

A lot of folks worry about China "owning" us. Honestly? That's a bit of a myth. Most of our debt is actually owned by us—American citizens, the Social Security Trust Fund, and the Federal Reserve. Foreign nations like Japan and China own a significant chunk, sure, but they aren't the majority. The real danger isn't a foreign country "calling in the loan"; it's the interest.

The Interest Trap: Why This Time is Different

When interest rates were near zero for a decade, the massive debt didn't actually cost that much to maintain. It was like having a giant mortgage with a 1% interest rate. You can handle a big loan if the payments are low. But as the Federal Reserve raised rates to fight inflation starting in 2022, the "cost to carry" that debt exploded.

✨ Don't miss: Is Walmart open Thanksgiving? Why the retail giant finally stopped the holiday madness

We are now reaching a point where the interest payments alone are starting to rival the entire defense budget. That is a massive shift in the U.S. debt history graph narrative. It’s no longer just about what we borrowed; it’s about what it costs to keep borrowing.

Critics of the current trajectory, like those at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), argue that we are headed for a fiscal crisis. They point out that Social Security and Medicare are facing insolvency in the next decade or so. If we don't change the trajectory, the interest payments could eventually crowd out all other government spending. No money for roads. No money for schools. Just interest.

On the flip side, proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argue that a country that prints its own currency can't really "go broke" in the traditional sense. They suggest the only real limit on debt is inflation. If you spend too much and cause prices to skyrocket, you've hit the wall. Given the inflation we saw in 2021 and 2022, that argument is getting a very public, very painful trial run.

Actionable Insights: How to Read the Data Yourself

Don't just take a politician's word for it. They usually cherry-pick the most dramatic-looking slice of the graph to scare you into voting for them. If you want to actually understand the fiscal health of the country, follow these steps:

- Check the Debt-to-GDP Ratio: This is the only metric that matters for long-term sustainability. The nominal dollar amount ($34T, $35T, etc.) is just a big number without context. Look at FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) for the most accurate, non-partisan charts.

- Look at Net Interest Costs: Keep an eye on how much of the federal budget goes toward paying interest. If that number crosses 15-20% of total revenue, we are in a high-pressure zone.

- Distinguish Between "Public" and "Intragovernmental" Debt: A lot of the debt is the government basically owing itself money (like the Social Security Trust Fund). While it still matters, "Debt Held by the Public" is the one that affects market interest rates and global stability more directly.

- Watch the CBO Projections: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is non-partisan and releases a "Long-Term Budget Outlook" every year. It’s dry, boring, and absolutely essential reading if you want to see where the graph is headed over the next 30 years.

The U.S. debt history graph is a mirror of our national priorities. It shows every war we fought, every crisis we weathered, and every economic gamble we took. It’s not just a line; it’s a scoreboard. Whether we can keep the game going depends entirely on whether we can grow the economy faster than we grow the interest. History shows we've done it before, but the current slope of that line suggests we're running out of runway.

To stay informed, monitor the quarterly Treasury announcements. They tell you exactly how much the government plans to borrow in the coming months. When those numbers spike unexpectedly, that's when you should start paying closer attention to your own portfolio and the broader market's reaction to "risk-free" Treasury bonds.