You’ve seen them. Those little orange or tan blotches scattered across the Western United States on a standard atlas. If you look at a US Indian reservations map, it looks like a simple collection of islands. Neat. Defined. Contained.

But honestly? That map is lying to you. Or at least, it’s not telling you the whole story.

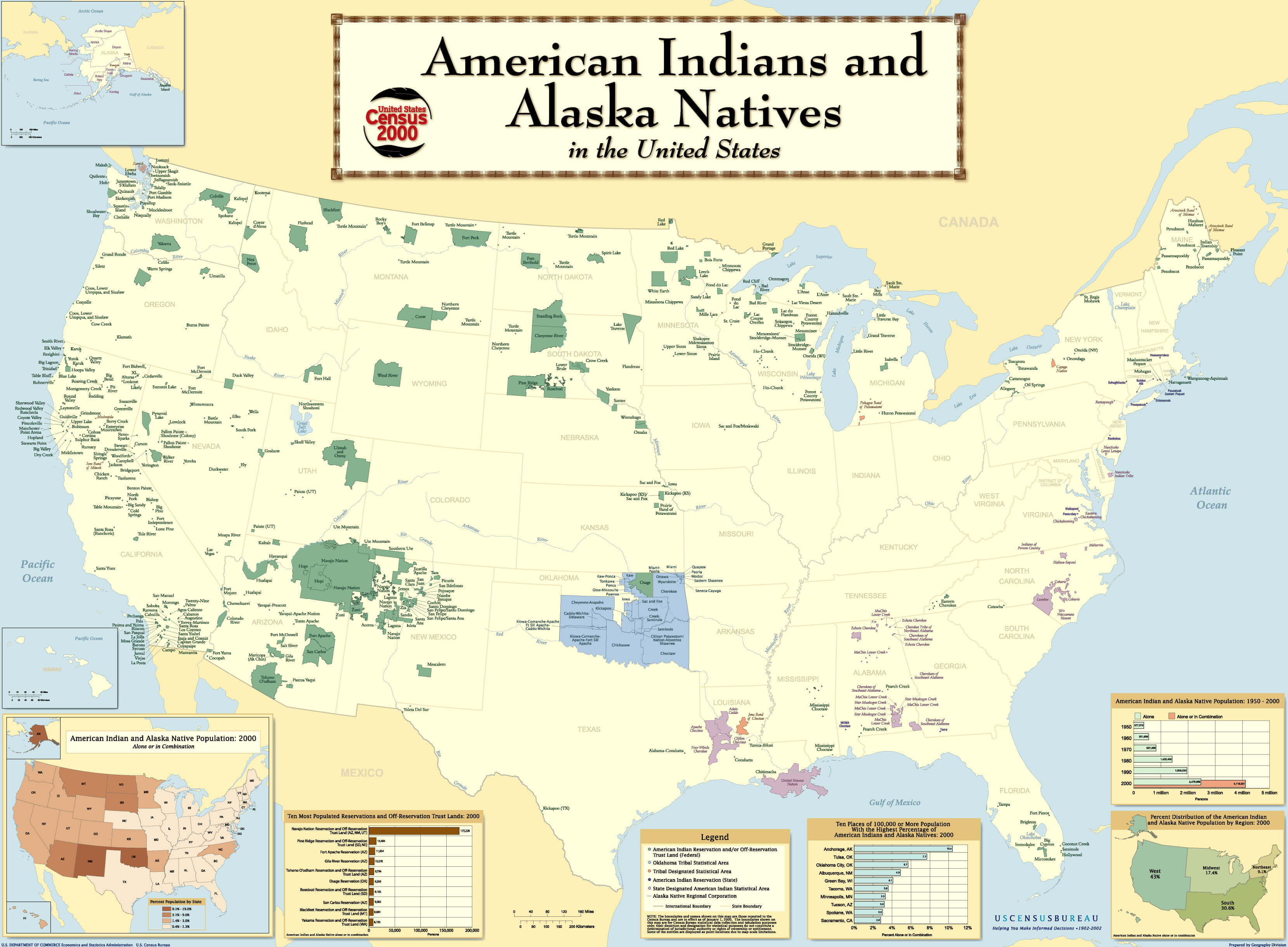

Most people look at a map of tribal lands and see a static piece of history, something settled in the 1800s and left alone. In reality, these borders are some of the most legally complex, politically charged, and physically diverse spaces in North America. We’re talking about 574 federally recognized tribes, each with its own relationship to the land. Some reservations are larger than the state of West Virginia, like the Navajo Nation, while others are just a few acres of "rancheria" tucked behind a California highway.

The Checkerboard Trap

When you zoom in on a US Indian reservations map, you expect to see a solid block of color. You won't always find that. Take the Spirit Lake Reservation in North Dakota or the Yakama Nation in Washington. If you were to walk across them with a high-detail survey, you’d realize you’re constantly stepping in and out of tribal jurisdiction.

This is what experts call "checkerboarding."

It’s a mess. Basically, the General Allotment Act of 1887—also known as the Dawes Act—broke up communal tribal lands into individual plots. The "surplus" was sold to non-Native settlers. Today, a single mile of road might pass through land owned by the tribe, land owned by a private non-Native farmer, and land held in trust by the federal government.

This creates a jurisdictional nightmare. Who pulls you over if you’re speeding? Who investigates a crime? The map makes it look like one big unit, but the reality is a patchwork quilt that was intentionally designed to fray at the edges.

Why the Map Looks the Way It Does

It isn’t a coincidence that the vast majority of the color on a US Indian reservations map is pushed west of the Mississippi.

The Trail of Tears wasn't just a tragedy; it was a massive geographic restructuring. If you look at an interactive map provided by the U.S. Census Bureau or the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), you’ll notice a huge gap in the South and the Mid-Atlantic. Tribes like the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Choctaw were forcibly moved from their lush ancestral homelands to "Indian Territory"—what we now call Oklahoma.

Speaking of Oklahoma, things got weird recently.

In 2020, the Supreme Court case McGirt v. Oklahoma fundamentally changed how we interpret the US Indian reservations map. The court ruled that much of eastern Oklahoma remains a reservation for the purposes of federal criminal law. Suddenly, about 40% of the state was "re-mapped" in the eyes of the law. It didn't mean people lost their private property, but it proved that these borders aren't just dusty relics from the 19th century. They are active, legal entities that can shift with a single court ruling.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Florida River Shark Teeth Fossils: What Nobody Tells You About the Peace River

More Than Just "Land"

There is a massive difference between "Tribal Trust Land" and "Fee Land."

Trust land is held by the federal government for the benefit of the tribe. You can't just buy or sell it. Fee land is owned outright by individuals. When you look at a US Indian reservations map, it rarely distinguishes between the two, which is why people get confused when they see a Starbucks or a massive non-Native housing development right in the middle of a reservation.

- The Navajo Nation: Spans 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It’s a literal sovereign nation with its own police, parks, and laws.

- The Wind River Reservation: Located in Wyoming, shared by the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho. It’s rugged, beautiful, and deeply complex in its dual-governance.

- The Pueblos of New Mexico: These aren't just reservations; they are some of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America, like Taos Pueblo.

The Misconception of the "Empty" West

People often use a US Indian reservations map to find "wilderness." That’s a bit of a colonial mindset, isn't it? These aren't empty spaces. They are inhabited nations.

If you're traveling through the Southwest, you might drive for three hours across the Navajo Nation. You’ll see red rocks, sure, but you’ll also see grazing livestock, schools, and thriving businesses. You’re crossing an international border in every sense except for the passport check.

Wait—actually, sometimes there are checks. During the 2020 lockdowns, the Navajo Nation famously closed its borders to outside traffic to protect its elders from COVID-19. They had the legal right to do it. The map stayed the same, but the border became very real, very fast.

Digital Mapping and the Future

We’re finally getting better tools. Organizations like Native Land Digital have created maps that show ancestral territories, not just current reservation boundaries. This is crucial because a US Indian reservations map only shows where tribes were forced to stay, not where they actually belong.

If you look at the Great Sioux Reservation of 1868, it was massive. It covered the entire western half of South Dakota. Then gold was found in the Black Hills.

📖 Related: Cedar Point to Cleveland: How to Survive the Drive After a Day of Roller Coasters

The map shrank.

It shrank again.

Today, the Great Sioux Nation is broken into several smaller reservations like Pine Ridge and Rosebud. When you look at the current map, you’re looking at the results of a shrinking process. It's a record of lost battles and broken treaties just as much as it is a guide for navigation.

Natural Resources and the Map

Why do some reservations have jagged, weirdly specific lines? Usually, it's about what's underneath the dirt.

Coal, oil, uranium, and water rights.

The boundaries on a US Indian reservations map often skirt around valuable mineral deposits or follow the flow of vital rivers. In the Pacific Northwest, tribal lands are intimately tied to salmon runs. In the Dakotas, it’s about the Missouri River. You cannot understand the geography of the US without understanding that these lines were often drawn by people who were trying to keep the "good stuff" for the federal government while giving the "barren" land to the tribes.

Joke’s on them, though—a lot of that "barren" land turned out to be sitting on massive energy reserves.

Practical Steps for Using These Maps Correctly

If you are a traveler, a student, or just someone curious about the geography of the country, don't just glance at a PDF and think you've got it.

First, understand that sovereignty is local. If you’re planning to visit, check the specific tribe’s website. Don’t assume that because you can hike in one reservation, you can hike in another. Some tribes, like the Havasupai in the Grand Canyon, require highly competitive permits months or years in advance.

Second, use the BIA’s TAMS (Trust Asset Management System) data if you need legal accuracy. It’s dry and technical, but it’s the only way to see the actual trust boundaries that hold up in court.

💡 You might also like: Empellón 510 Madison Ave New York NY 10022: Why This Isn't Just Another Taco Joint

Third, look at the overlapping territories. Many tribes claim the same ancestral sites. A standard US Indian reservations map won't show you this overlap, but it’s where the most interesting history (and current legal battles) happens.

Moving Beyond the Paper Lines

The most important thing to remember is that these maps represent living people.

There are over 5 million Native Americans in the US. About half live on or near the lands shown on a US Indian reservations map. The other half live in urban centers like Chicago, Denver, or Los Angeles, often because of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, which was another federal attempt to dissolve tribal identity by moving people off the map entirely.

So, the next time you see those colored shapes on a map, think of them as breathing entities. They are sites of resilience. They are places where languages are being revived and where legal precedents are being set that affect every American.

Actionable Insights for the Informed Viewer

- Always Cross-Reference: Compare a current reservation map with a map of ancestral territories to see the scale of land loss.

- Check Jurisdiction: If you are conducting business or traveling, remember that tribal law often supersedes state law on "Indian Country."

- Support Tribal Tourism: Many tribes have official tourism departments. Use the map to find these offices rather than just wandering onto private allotment land.

- Respect the Border: Treat the entrance to a reservation with the same respect you would a state or national border. Often, there are specific laws regarding photography, alcohol, and land use that are strictly enforced by tribal rangers.

- Acknowledge the Land: Use tools like Native-Land.ca to understand whose traditional territory you are standing on, regardless of whether it’s an official reservation or not.