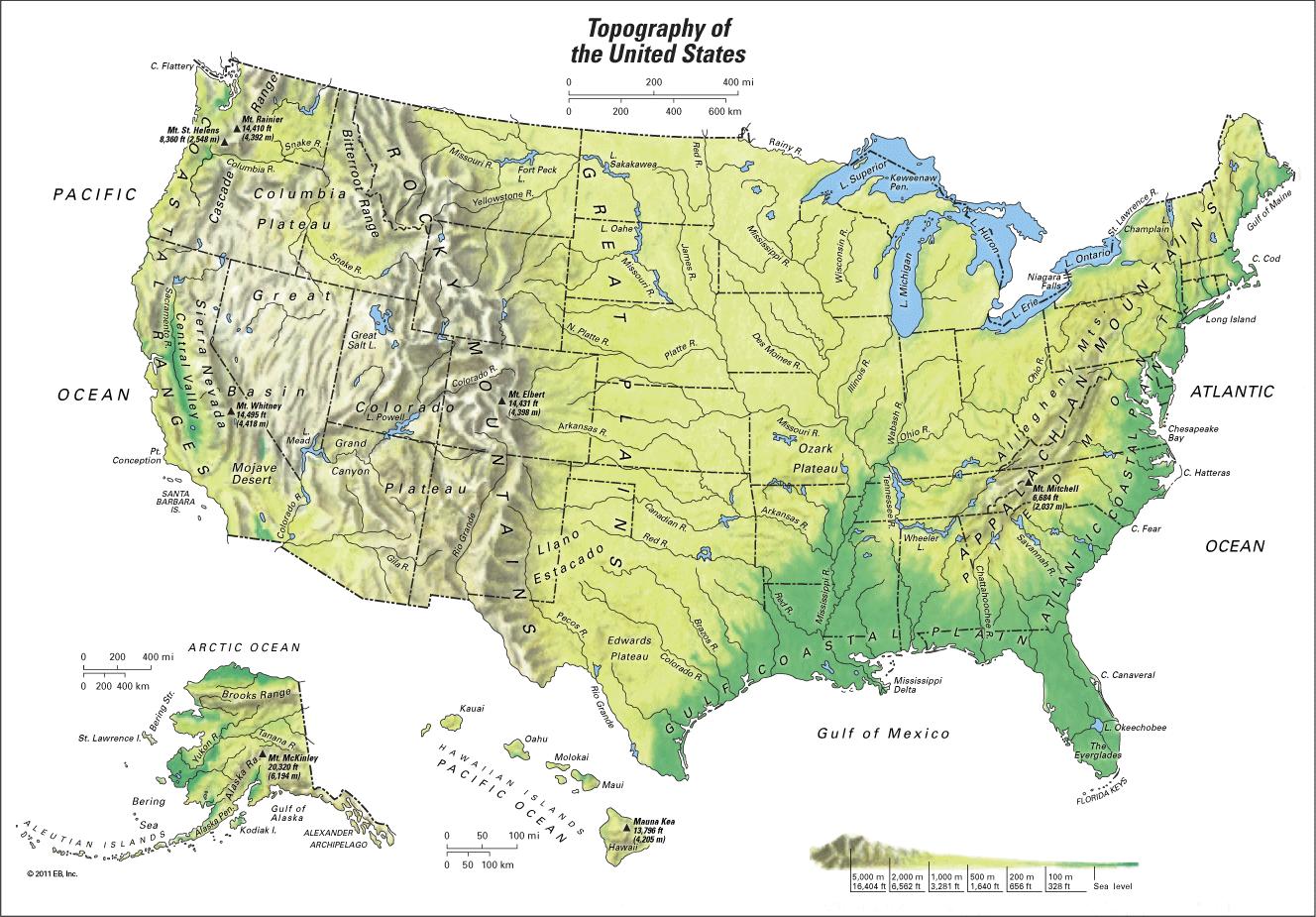

Look at a US map of mountain ranges and you’ll see two giant vertical scars framing the country. On the right, the old, crumbly Appalachians. On the left, the jagged, aggressive Rockies. It looks simple. Most of us grew up with this mental image—a flat middle part sandwiched between two big bumps. But honestly? That map is lying to you. Or at least, it’s leaving out the best parts.

Nature doesn't care about clean lines. If you actually zoom in on the topography of the United States, you realize it’s a chaotic mess of volcanic plugs, folded sedimentary rock, and massive batholiths that don't always fit into the "two-range" narrative.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Your Way: What the City Map of Panama City Panama Actually Tells You

The Eastern Divide: More Than Just the Appalachians

The Appalachians get a bad rap. People call them "hills." That’s a mistake. While they don't have the 14,000-foot peaks of Colorado, they are geologically ancient—hundreds of millions of years older than the Rockies. They once stood as tall as the Himalayas before the relentless grind of erosion wore them down. When you check a US map of mountain ranges, the Appalachian system actually stretches from Alabama all the way into Canada, but it’s broken into distinct "provinces" like the Blue Ridge, the Ridge and Valley, and the Allegheny Plateau.

Ever heard of the Black Mountains in North Carolina? They house Mount Mitchell. At 6,684 feet, it’s the highest point east of the Mississippi. It's rugged. It's often covered in a dense, subalpine spruce-fir forest that feels more like Canada than the American South. The Blue Ridge Mountains, which host the famous Parkway, are actually a distinct geological feature characterized by metamorphic rock.

Then there's the Great Smoky Mountains. They aren't just a tourist trap. They are a biodiversity hotspot. Because the glaciers of the last Ice Age stopped just north of this region, the Smokies became a refuge for thousands of species. This is why you see such a bizarre mix of plants there today.

Further north, the Green Mountains of Vermont and the White Mountains of New Hampshire provide a much harsher environment. Mount Washington is famous for having some of the worst weather on Earth. We’re talking 231 mph wind gusts. It’s a reminder that elevation isn't the only thing that makes a mountain dangerous.

The Western Giants: A Geography of Violence

The West is different. It's loud. It’s dramatic. It’s the result of tectonic plates smashing into each other like a slow-motion car crash.

✨ Don't miss: US Travel to Russia: What You Actually Need to Know Right Now

When people look for the Rockies on a US map of mountain ranges, they usually see one big brown blob. In reality, the Rocky Mountains are a collection of over 100 separate ranges. You have the Front Range in Colorado, the Wind River Range in Wyoming, and the Bitterroots in Montana. They were formed during the Laramide orogeny, a period of mountain-building that happened roughly 80 to 55 million years ago.

The Cascades vs. The Sierras

Don't confuse the two. They are totally different beasts.

The Sierra Nevada in California is basically one giant block of granite tilted upward. It’s home to Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous US. If you’ve ever seen the "walls" of Yosemite, you’ve seen the heart of the Sierras. It's solid. It's grey. It's stunning.

The Cascades, running through Oregon and Washington, are a "range of fire." These are volcanoes. Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, Mount Hood—these aren't just piles of rock; they are active threats. They sit on the Pacific Ring of Fire. When you look at them on a map, they appear as isolated, towering cones rather than a continuous wall of granite like the Sierras.

The "Missing" Mountains in the Middle

There is a huge misconception that the area between the Appalachians and the Rockies is just cornfields. That’s wrong.

Take the Ozarks. Located primarily in Missouri and Arkansas, the Ozark Plateau is often called a mountain range, but geologically, it’s a dissected plateau. The rivers have spent eons carving deep valleys into the uplifted rock, creating a landscape that looks and feels like mountains.

Then you have the Black Hills of South Dakota. They sit out there all by themselves. They are an "outlier." Geologically, they are more closely related to the Rockies than anything nearby, rising up like an island from the Great Plains. To the Lakota people, this is Paha Sapa, the center of the world. Seeing them pop up on a flat horizon is one of the most jarring geographical experiences in America.

Why the Basin and Range Province Messes Everything Up

Between the Sierras and the Rockies lies the Great Basin. On a US map of mountain ranges, this area looks like a series of "caterpillars crawling north," as geologist Clarence Dutton famously described it. This is the Basin and Range Province.

It covers most of Nevada and parts of Utah and Arizona. It isn't one range. It’s hundreds of small, parallel ranges separated by flat valleys. It’s the result of the Earth’s crust literally being pulled apart. Because the crust is stretching, it thins out and breaks into blocks. Some blocks drop down (basins), and others tilt up (ranges).

If you’re driving across Nevada on I-80, you’re constantly going up over a pass and down into a flat basin. Over and over. It’s a unique landscape that you won't find anywhere else in the world on this scale.

✨ Don't miss: Backbone Rock Campground TN: Why This Tiny Spot Is Actually Worth The Drive

Mapping the Extremes: Alaska and Hawaii

We often forget the non-contiguous states when talking about a US map of mountain ranges, which is a shame because Alaska puts the Lower 48 to shame. The Alaska Range contains Denali. At 20,310 feet, it’s so big it creates its own weather systems.

Alaska’s mountains are still growing. They are raw and unforgiving. The Brooks Range in the north is entirely above the Arctic Circle—a place where the sun doesn't rise for weeks in the winter.

Hawaii is the opposite. It’s the top of a massive underwater volcanic chain. Mauna Kea, if measured from its base on the ocean floor, is technically taller than Everest. It’s a shield volcano, meaning it’s broad and gently sloping, built by layer upon layer of fluid lava.

The Realities of Living Near These Ranges

Mountains dictate everything. They decide where the rain falls. The "rain shadow" effect is why the western side of the Cascades is a lush rainforest while the eastern side is a desert. They decide where cities are built. Denver exists because of the Rockies. Salt Lake City is tucked against the Wasatch Range.

They also dictate risk. Wildfires in the West are exacerbated by mountain topography, which can funnel winds and make fires nearly impossible to contain. In the East, the mountains contribute to flash flooding, as steep hollows trap water and send it roaring down into small communities.

Actionable Steps for Exploring US Mountains

If you want to truly understand these landscapes beyond a static map, you need to change how you look at them.

- Use Topographic Layers: Instead of a standard road map, use tools like CalTopo or Gaia GPS. Switch to a "Shaded Relief" or "Contour" view. This reveals the "grain" of the land that flat maps hide.

- Study the "Gaps": Look for places like the Cumberland Gap or the South Pass in Wyoming. These low points in the mountain ranges are the reason the US expanded the way it did. They were the "gateways" for pioneers.

- Visit a National Park Outlier: Skip the Grand Canyon for a moment. Go to North Cascades National Park in Washington (the "American Alps") or Big Bend in Texas, where the Chisos Mountains rise out of the desert.

- Understand the Rock: Grab a roadside geology book for your state. Knowing why the rock is red in Sedona but grey in the High Sierra changes how you perceive the "bumps" on the map.

The US map of mountain ranges is a living document. Erosion is still happening. Tectonic plates are still shoving. Volcanoes are still gurgling. To see these ranges as static lines on a page is to miss the entire story of the continent. Get out there. Drive the mountain passes. Feel the temperature drop as you climb. That’s the only way to map the country for real.