Ever looked at a Utah and Wyoming map and thought, "That’s just two big squares with a weird notch"? Honestly, you aren't alone. Most people see the rectangular silhouettes of the Mountain West and assume the geography is as flat and predictable as the paper it’s printed on.

It isn't. Not even close.

💡 You might also like: Why the Highland Park Police Museum in Los Angeles is Still a Hidden Gem

That "notch" in the corner where Utah’s shoulder tucks into Wyoming's side? That’s a result of 19th-century political drama, anti-Mormon sentiment, and some of the most rugged terrain in the lower 48. If you're planning a road trip or just trying to figure out where the Salt Lake influence ends and the Cowboy State begins, you've got to look past the lines.

The Mystery of the Missing Corner

If you trace your finger along a Utah and Wyoming map, you’ll hit a jagged 90-degree turn in the northeast. This isn't a mistake. Back in the 1850s, the Utah Territory was massive. It stretched all the way to the Sierra Nevada. But when the Wyoming Territory was carved out in 1868, Congress basically took a bite out of Utah.

Why? Part of it was practical. The Uinta Mountains—one of the only major ranges in North America that runs east-to-west—created a massive physical barrier. It was way easier for authorities in Cheyenne to manage that northern patch than it was for folks in Salt Lake City to climb over 13,000-foot peaks to get there.

But there’s a messier side to the history, too. The federal government was pretty keen on shrinking Utah's influence at the time, mostly due to friction with the LDS Church. By shifting the border, they ensured more land (and potential mineral wealth) stayed under "gentile" control in Wyoming.

High Deserts and Vertical Walls

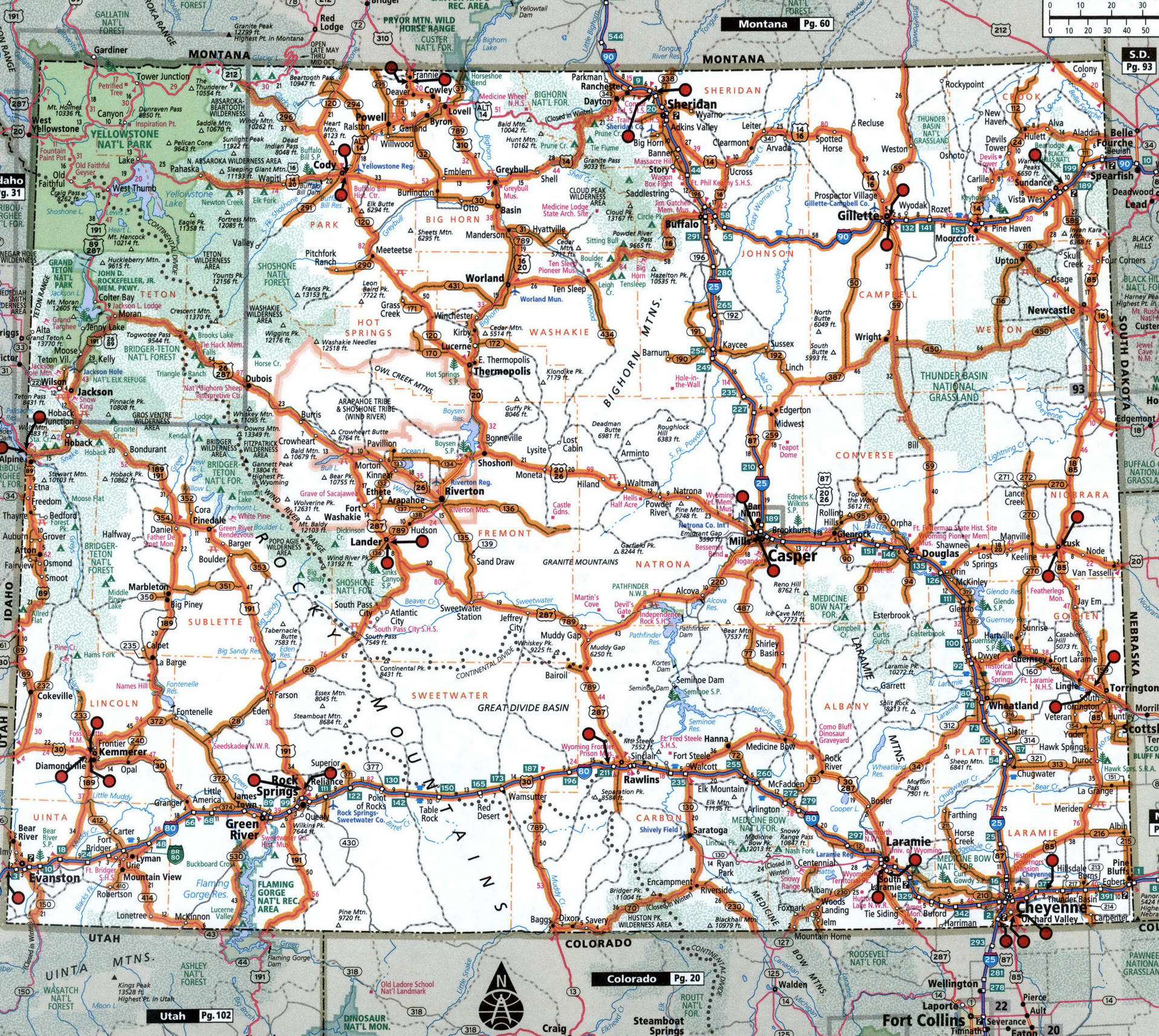

When you look at a topographical Utah and Wyoming map, the colors change fast. You go from the sagebrush-heavy Wyoming Basin into the jagged teeth of the Wasatch and Uinta ranges.

- The Uinta Mountains: This is the big one. Most people don't realize these mountains are a geological anomaly. They don't follow the north-south "spine" of the Rockies. On a map, they look like a horizontal bar blocking the path between Salt Lake City and the Wyoming border.

- The Bear River: This river is a bit of a nomad. It starts in Utah, loops up into Wyoming, swings into Idaho, and then decides to come back down to the Great Salt Lake. Following its path on a map is like watching a toddler wander through a grocery store.

- The Flaming Gorge: This is where the map gets really pretty. The Green River carves through deep red siltstone, straddling the border. Half the reservoir is in Wyoming, half is in Utah. If you’re fishing here, you literally need to know exactly where that invisible line is on the water, or you'll need two different permits.

Navigating the "Interstate Gap"

If you're driving, your Utah and Wyoming map is basically dominated by two lifelines: I-80 and I-15.

I-80 is the workhorse. It cuts through Evanston, Wyoming, and drops you right into the heart of the Wasatch Front. It’s a brutal drive in the winter. We're talking "highway-closed-for-three-days" kind of brutal. The wind coming off the Wyoming plains can flip a semi-truck like a pancake.

Kinda wild, right? You’re driving through what looks like an empty landscape on the map, but the atmospheric pressure and elevation (Sisters Lookout is over 7,000 feet) make it one of the most dangerous stretches of road in the country.

Then you’ve got the scenic route—US-89. If you want to actually see the "real" border country, this is it. It takes you through Logan Canyon and spits you out at Bear Lake.

The Bear Lake Split

Look closely at the Utah and Wyoming map right at the top of Utah. You’ll see a bright blue spot called Bear Lake. The state line slices it nearly in half.

The locals call it the "Caribbean of the Rockies" because the water is this insane turquoise color. This happens because of suspended calcium carbonate (limestone) particles. It’s a literal geographic gem hidden in a high-mountain valley. If you’re there in July, you’ve got to try the raspberry shakes in Garden City. It’s basically a law.

Where the Maps Get Complicated: Public Lands

One thing a standard road Utah and Wyoming map won't show you clearly is the checkerboard.

In the 1800s, the government gave alternating square-mile sections of land to railroad companies to encourage the transcontinental line. Today, that means the border region is a mess of private and public land. One mile you’re on BLM (Bureau of Land Management) ground where you can camp for free; the next, you’re trespassing on a private ranch.

If you're using a digital map like OnX or Gaia GPS, you’ll see this "checkerboard" pattern. It’s a headache for hunters and hikers, but it’s a living relic of how the West was built.

🔗 Read more: Why Bow Bridge New York is Actually the Most Important Spot in Central Park

Real Talk: The "Empty" Spaces

There’s a section on the Utah and Wyoming map between Rock Springs and Vernal that looks... well, empty.

It’s not.

This is the Red Desert and the Uinta Basin. It’s one of the last great wild places. You’ve got wild horses, massive herds of elk, and some of the richest fossil beds in the world. Dinosaur National Monument sits right on the border. You can stand in Utah and look at a wall of dinosaur bones, then walk a few miles east and be in the Wyoming wilderness.

People skip this because the map doesn't show many towns. Honestly? That’s the best reason to go.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

If you’re planning to use a Utah and Wyoming map to actually explore, don't just rely on Google Maps. It’ll send you the fastest way, which is usually the most boring.

- Check the WYDOT and UDOT apps. In 2026, these are way more accurate for mountain pass closures than generic GPS.

- Download offline layers. Cell service dies the second you leave the interstate. If you don't have the map saved to your phone, you're navigating by the sun.

- Watch the gas gauge. Between Evanston and Rock Springs, or Vernal and Manila, stations are rare. If you hit half a tank, fill up.

- Respect the "Notch." If you're heading into the Uintas from the Wyoming side (near Evanston), remember that the highest peaks are actually back in Utah.

The border between these two states isn't just a line on a Utah and Wyoming map. It’s a transition between the high plains and the deep desert, a collision of history and geology that still defines how we move through the West today.

For your next move, get a high-resolution topo map of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest. It covers the meat of the border region and shows the trails that the highway maps completely ignore. Look for the "High Uintas Wilderness" section—it's the best way to see the actual geography that forced the mapmakers to draw those weird lines in the first place.