You’re probably here because someone mentioned a "pacemaker for the brain" or you've been scrolling through TikTok seeing people rub ice cubes on their chests. It's a weird world. But for people dealing with treatment-resistant epilepsy or a depression that just won't quit, vagus nerve stimulation placement is a serious, life-altering medical conversation. We aren't just talking about a wellness hack here; we're talking about a surgical procedure that tethers a piece of high-tech hardware to the longest cranial nerve in your body.

The vagus nerve is basically the body's superhighway. It starts in the brainstem and wanders—hence the name "vagus," Latin for wandering—all the way down to your abdomen. It touches your heart, your lungs, and your gut. When doctors talk about placement, they’re usually referring to the left side of your neck. Why the left? Because the right vagus nerve has a more direct line to the heart’s sinoatrial node. Messing with the right side can cause some pretty sketchy cardiac issues, so surgeons almost always stick to the left.

The Surgical Reality of Vagus Nerve Stimulation Placement

It’s not a brain surgery. That’s the first thing people usually get wrong. The procedure, often performed by a neurosurgeon like Dr. James Goodrich or specialists at clinics like the Mayo Clinic, involves two small incisions. One is in the neck to find the nerve, and the other is in the chest wall to tuck in the pulse generator.

The generator is about the size of a pocket watch, though modern versions from companies like LivaNova are getting smaller and thinner every year. Think of it like a silver dollar that’s been hitting the gym. It sits just under the skin below the collarbone. Lead wires are tunneled under the skin from the chest up to the neck, where they are wrapped around the left vagus nerve.

The surgery takes about an hour or two. Most people go home the same day.

Honestly, the "placement" isn't just about where the metal sits. It's about how those leads interface with the nerve fibers. The surgeon uses tiny silicone coils to anchor the electrodes. If they’re too tight, they can damage the nerve. If they’re too loose, the connection is spotty. It’s a delicate balance of biomechanics.

Why the Left Side?

Science is funny about symmetry. While our bodies look mostly the same on both sides, the plumbing is different. The right vagus nerve carries more fibers that regulate heart rate. Stimulating it could, theoretically, stop your heart or cause a dangerous drop in blood pressure.

The left vagus nerve is different. It’s "safer." It still communicates with the brain to tell it to calm down during a seizure or to rebalance neurotransmitters in a depressed brain, but it does so without the same level of cardiac risk.

Some researchers are looking into right-sided stimulation for specific heart failure protocols, but for the standard FDA-approved uses—epilepsy and depression—the left side is the gold standard.

What Happens After the Device is In?

The device doesn't start zapping you the moment you wake up. Doctors usually wait a few weeks for the incisions to heal before they turn it on. This is where the "programming" phase starts. You’ll go into the office, and a neurologist will hold a wand over your chest—basically a specialized tablet—to talk to the generator.

They start with a low current. You might feel a tingle. You might cough.

- Frequency: How often the pulses happen.

- Pulse Width: How long each pulse lasts.

- Signal Current: The "strength" or intensity.

It’s a slow climb. If the current is too high, your voice might change. You’ll sound like you’re talking through a fan or maybe get a bit raspy. This happens because the vagus nerve sits right next to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which controls your vocal cords. It’s a common side effect, but most people get used to it or the settings are tweaked to minimize the "vagus voice."

The "Magnet" Trick

One of the coolest (and most practical) parts of vagus nerve stimulation placement is the external magnet. Patients get a magnet they can wear on their wrist or belt. If an epileptic patient feels an aura—that "it’s coming" feeling before a seizure—they can swipe the magnet over the generator in their chest.

This triggers an extra burst of stimulation.

It can stop a seizure in its tracks or at least make it shorter and less intense. For families, this provides a massive sense of agency. You aren't just waiting for the storm to pass; you have a literal "stop" button on your chest.

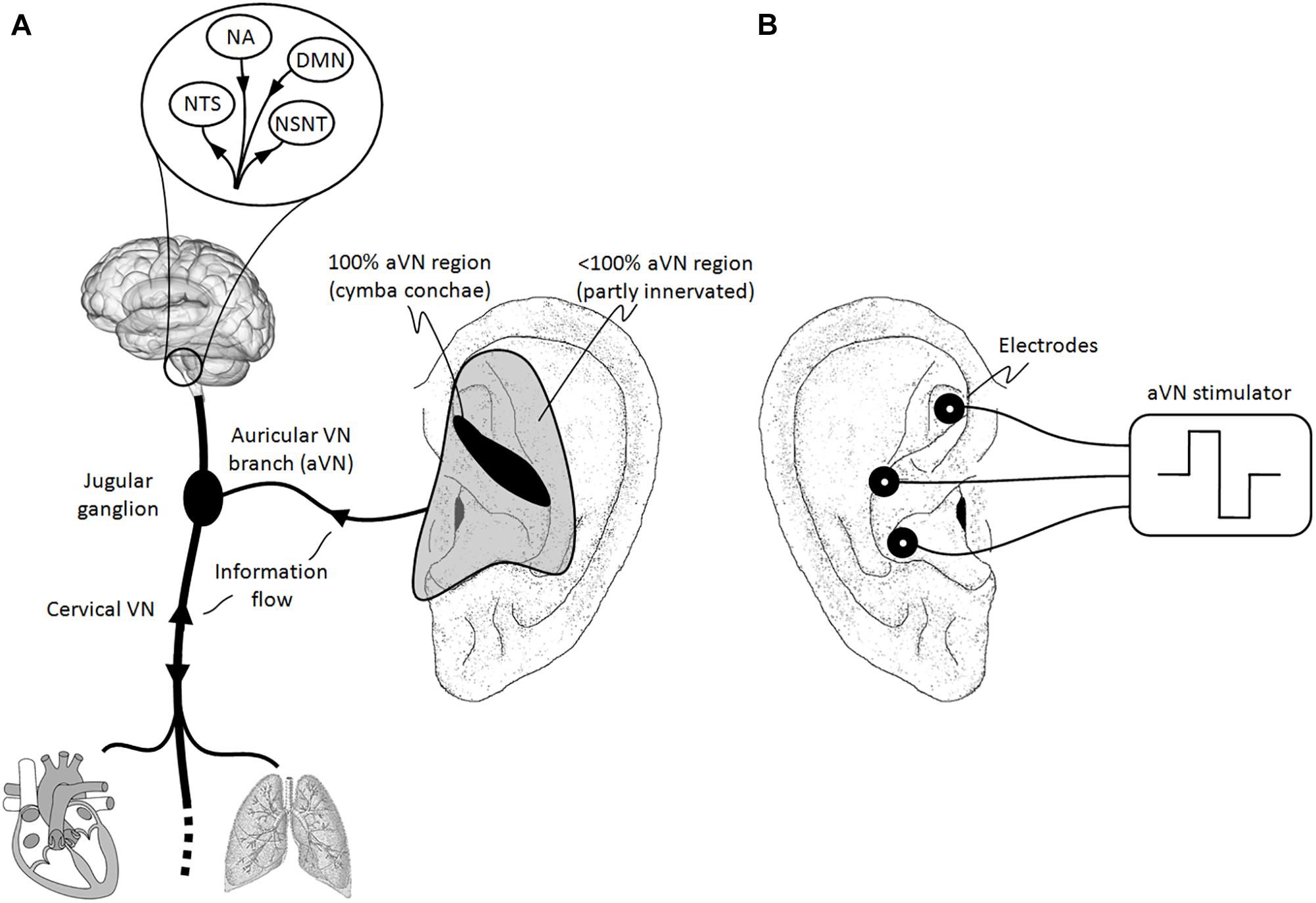

Non-Invasive Options: The New Frontier

Not everyone wants to go under the knife. In recent years, we’ve seen the rise of transcutaneous VNS (tVNS). This is vagus nerve stimulation placement without the surgery.

Instead of an implanted lead, these devices target branches of the vagus nerve that surface near the skin. There are two main spots:

✨ Don't miss: Cleaning Whiteheads on Nose: Why Most DIY Methods Actually Fail

- The Tragus: That little bump of cartilage in front of your ear canal.

- The Neck: Specifically the area where the carotid artery pulses.

Devices like the gammaCore are FDA-cleared for migraines and cluster headaches. You hold it against your neck, it sends a signal through the skin, and it hits the nerve. It’s not as constant as an implant, but for someone who can't have surgery or doesn't need 24/7 stimulation, it’s a game-changer.

But let’s be real: tVNS is not the same as a surgical implant. The "dose" is different. The consistency is different. If you have severe, intractable epilepsy, a handheld device likely won't cut it.

The Risks Nobody Likes to Talk About

Every surgery has a "but."

With VNS placement, the risks include infection at the site of the generator or the neck lead. There’s also the risk of lead migration. These wires are flexible, but if you’re a very active person or you happen to take a hard fall, that wire can shift. If it shifts, the stimulation might hit the wrong fibers, leading to pain or vocal cord paralysis.

It’s rare. But it happens.

Then there’s the battery. These things aren't infinite. Depending on the settings, the battery lasts anywhere from one to ten years. When it dies, you need another surgery to swap out the generator. They don't usually have to replace the neck leads, thankfully, but you're still looking at a trip back to the OR.

Deep Tissue Realities: What It Feels Like

People ask: "Can I feel it?"

Mostly, no. You’ll feel the bump under your skin. If you’re lean, you might see the outline of the generator. But the stimulation itself? It’s a weird sensation. Some describe it as a mild tightening in the throat or a slight urge to cough. After a few months, the brain usually "tunes out" the sensation, a process called habituation.

Interestingly, some patients report that they actually like the feeling. It becomes a tactile reminder that their "shield" is active.

Beyond Epilepsy: The Future of Placement

We are seeing a massive explosion in VNS research. Dr. Kevin Tracey, a pioneer in the "inflammatory reflex," has shown that the vagus nerve can actually turn off the production of inflammatory cytokines. This means VNS placement might eventually be a standard treatment for:

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Crohn’s Disease

- Post-Stroke Recovery (the FDA actually approved it for this in 2021)

For stroke recovery, the placement is the same, but the timing is different. The device is paired with physical therapy. When the patient performs a movement correctly, the device triggers. It tells the brain, "Hey, pay attention! This move was important." It’s basically neuroplasticity on steroids.

Practical Steps If You're Considering VNS

If you or a loved one are looking into this, don't just jump at the first surgeon you see.

First, get an evaluation at a Level 3 or 4 Epilepsy Center if seizures are the issue. These centers have the multidisciplinary teams (neurologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists) needed to decide if VNS is actually the right move. Sometimes, a different type of surgery, like an RNS (Responsive Neurostimulation) or a resection, might be better.

Second, check your insurance. Because VNS is an "implantable," it’s expensive. Most major insurers cover it for epilepsy, but for depression, the "coverage landscape" is a bit more of a minefield.

✨ Don't miss: The 5'3 ideal weight female debate: Why the scale is lying to you

Third, ask your surgeon about the "model number." Newer models allow for MRI compatibility. This is huge. Older VNS implants made getting an MRI nearly impossible or very dangerous because of the metal and the magnetic fields. You want a device that won't lock you out of future diagnostic tools.

Lastly, manage your expectations. VNS is rarely a "cure." It’s a management tool. For epilepsy, the goal is often a 50% reduction in seizures. Some people get 100%, but many find that it just makes their bad days a lot less bad. That’s still a massive win, but it’s important to go in with eyes wide open.

Vagus nerve stimulation placement is a marriage of biology and engineering. It’s about taking a "wandering" nerve and giving it a GPS. Whether it’s through a surgical implant or a handheld device, we’re finally learning how to speak the electrical language of the body.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Consult a Specialist: If you have drug-resistant epilepsy or depression, request a referral to a neurologist who specializes in "neuromodulation."

- Verify MRI Compatibility: If you proceed with surgery, ensure the device is "MRI Conditional" so you aren't restricted from future imaging.

- Log Your Symptoms: Start a detailed diary of seizure frequency or mood scores now. You'll need this baseline to prove to insurance and your doctor that the device is actually working six months post-op.

- Test Non-Invasive First: If your condition allows (like for migraines), ask about trying a prescription-grade tVNS device before committing to a permanent surgical implant.